Terra nullius, or “land belonging to no one”, served as an ideological foundation for colonialism.

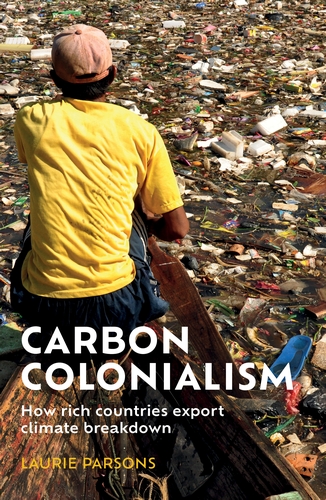

In his new book, Carbon Colonialism: How Rich Countries Export Climate Breakdown, University of London lecturer Laurie Parsons dives into how this same colonial paradigm shapes the global economy and the lives of millions.

Following 15 years of investigating where Cambodia fits into global supply chains for garments and other manufactured goods, Parsons is now shedding light on some of the most influential factors driving the worsening climate crisis.

Carbon Colonialism calls into question the myth of global prosperity and carbon reduction promised by laissez-faire capitalism.

Parsons spoke with Southeast Asia Globe about the motivation behind his book, the steps needed to reverse course and the “green shoots” of hope that are keeping him optimistic.

What led to the inception of this book?

This book brings together a lot of insights. Most of my career has been devoted to trying to make sense of all these different aspects of environmental pressures pushed by the global economy and explain how they manifest in Cambodia.

I’ve worked in almost every Cambodian province, at least 23 out of the 25, to try to make sense of different kinds of livelihoods and try to narrate the connection to the global systems wherein Cambodia sits.

Can you explain what you meant when writing this line: “[The] ability to sweep the uncomfortable, the unpalatable, the dirty, and the dangerous under the murky carpet of global production was always a feature of colonialism”?

This comes down to the great myth of colonialism. What kept the whole enterprise of colonialism going for hundreds of years was this idea of “terra nullius,” which means “empty lands” or “nobody’s lands.” That was the guiding lighthouse of colonialism. The idea it is fine to do whatever you want in these areas because anything colonists bring there is better than what is there.

That same essential logic purveys the way economic development happens. That idea that the expansion of the global economy into these regions must be better than the local economy is fundamental to the way our global economy behaves in the Global South.

For example, there is a lot less scrutiny around what happens when a new garment industry starts up in a country like Cambodia, because it is seen generally as a good thing. Nations in the Global North, like the U.K., believe that however we expand our global economy into those areas, is better than nothing.

What are the tangible impacts of ‘terra nullius’ continuing in countries, like Cambodia, which are on the receiving end of ‘carbon colonialism’?

It creates a massive incentive for all of the worst, dirtiest and cheapest elements of production to happen away from the regulation. This is a fundamental problem we have had in our global economy and society recently. We have certain areas of the world that are really heavily environmentally regulated, the rich parts. Then other parts of the world which are much more loosely regulated, the poor parts.

All of the worst parts of production get moved to the poorer, less regulated parts. This doesn’t necessarily happen because someone wants to do this evil thing, it is just what happens with incentives. If you have uneven regulation, and no legislative framework to stop that from happening, then the worst parts are going to move to where the regulation doesn’t reach. That is a key thing we see in Cambodia.

This relates to the idea of the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ approach to long and complex supply chains” that you wrote about in your book. Can that be changed?

Up to this point, there has been relatively little you can do. But that is just beginning to change. The positive thing is that we are beginning to finally see the first ‘green shoots’ of the mindset of global production beginning to emerge.

This year, the new Supply Chain Law in Germany comes into force. This will give anyone affected environmentally or by labour rights abuses by a company trading in Germany, the right to challenge that company in a German court. This is an absolute game-changer for the way we think about international production. Again, this is just a tiny green shoot.

We need to recognise the fact that wealthy countries aren’t wealthy because of what happens within their borders but because they are able to exploit this global system of production.

What paved the way for us to get to this point?

In the last 50 years, economies have outgrown politics. In developed countries, economies were contained within borders and both economy and politics matched each other. If the economy was doing something that people didn’t like, in theory, there was a chance to have some power over that.

But in the rich world now – in Europe, the U.K. and the U.S. – that has really changed. Our economy has gone global and our politics have stayed national. Huge multinational companies are developing their current power to essentially do whatever they want without any legislative pullback and that is a massive problem.

Are climate risks, in terms of natural disasters, an equaliser between the countries both perpetuating ‘carbon colonialism’ and experiencing it?

You can’t take money out of the equation when it comes to climate risk.

There is a distinction between a natural hazard, like strong winds or rising sea levels or heavy rain, and the disaster that results from that. Hazards only become disasters when they meet poverty and vulnerability.

When thinking about climate risk, you can not take out the global economy from the equation because that is what distributes the landscape of vulnerability and poverty.

Despite the “green shoots” emerging, how would you respond to a pessimistic reader?

Whether you take an optimistic or pessimistic viewpoint over the problems we face in our global environment comes down to whether you think it is possible for people to take power.

Positivity is difficult. But the first step is the hardest, which is overcoming the invisibility and the disconnectedness of everything – getting beyond the simplistic and misleading ways we conceptualise the supply chain.

If you’re not aware of the environmental context in which you live then you are essentially in a similar position to a house cat. As in, you believe in your independence and capacity to understand your own environment. But actually you are dependent on a system you are not aware of. Being aware of this kind of underlying logic to our global economy is crucial to any aspect of living our lives.

Don’t be a house cat.