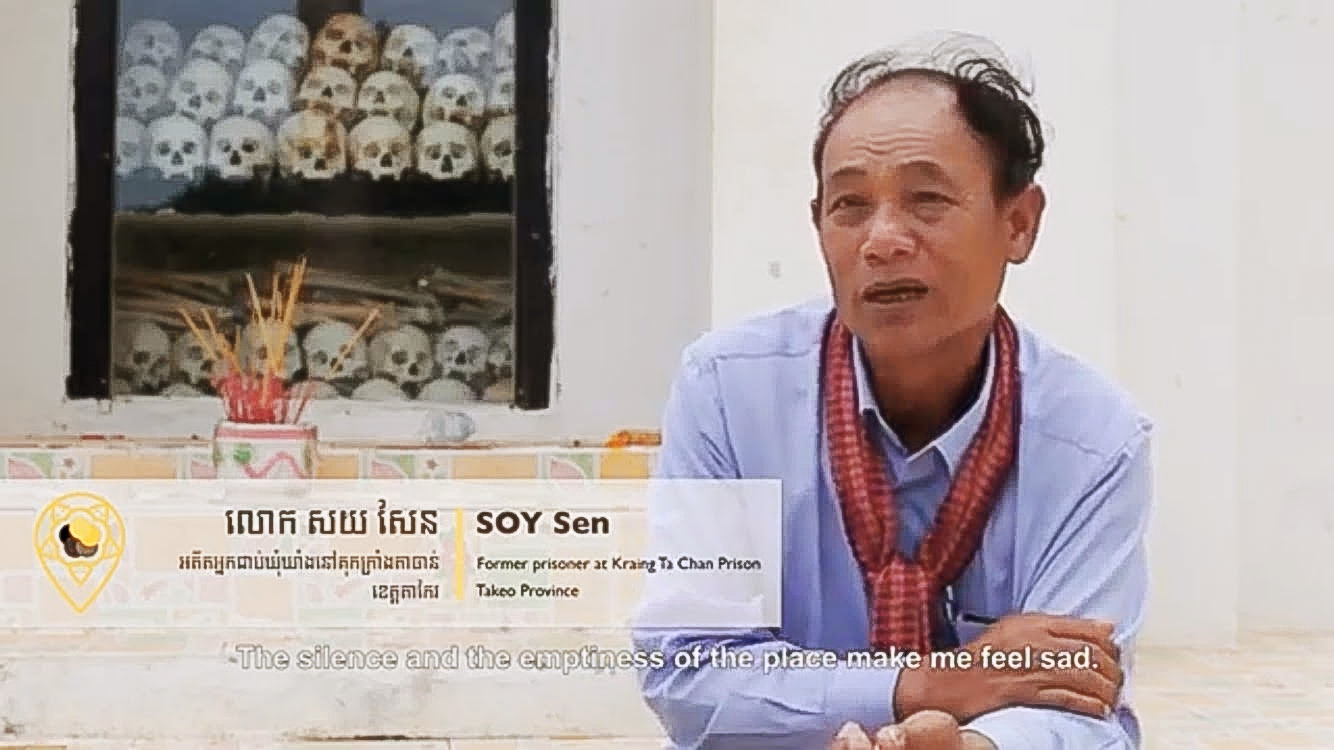

The old man’s face fills the screen of the smartphone as he walks through Kraing Ta Chan security centre in Takeo province, describing the long years of his childhood spent there. Wearing a red krama loose around his neck, he sits on the stoop outside of the detention-centre-turned-museum, the heaped skulls of those unable to escape the cruelty of the Khmer Rouge watching through the window behind him.

As the short documentary plays on, Soy Sen prepares to meet the man who saved his life. When he was just ten years old, Sen was imprisoned by the Khmer Rouge barely a year before the ultra-Maoist regime swept into Phnom Penh in 1975. Over the next four years, nearly two million Cambodians would lose their lives to famine, war and genocide. Now, 40 years after the fall of the regime, Sen is preparing to ask Phan Chhen, who he describes as “one of the top leaders of the prison”, why his life was spared.

“My feelings about Uncle Chhen have never ended,” he tells the camera.“I remember the fact that he told other prison guards not to kill me.”

The emotional meeting that follows is one of the dozens of personal stories of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge era that have been painstakingly documented and compiled by young Cambodian journalism students in a single online location: a new phone application called “Mapping Memories Cambodia”.

The first project of its kind, the mobile application and accompanying website seek to tell the tales of the Khmer Rouge years using a combination of journalism and technology.

Stories are recorded in written, podcast or video format and are tagged according to the geographic location where each recorded story took place: more than 50 sites of significance during the Khmer Rouge period have been marked on the map so far, spanning 18 cities and six of Cambodia’s provinces. Users can navigate through these historical sites to experience the history of a given location in a multimedia format, with all stories presented in both Khmer and English.

A product of the Department of Media and Communication (DMC) and its students, the project was put forth by Stefanie Duckstein, adviser to the Civil Peace Service (CPS), over a year ago and funded by both CPS and German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). Released on 30 January, the launch of the application was celebrated on 2 February and has already been downloaded more than 300 times.

Building skills

The aspiring reporters of the DMC who contributed stories to the new app are on course to complete an intensive four-year journalism degree. As part of their studies, they prepared stories for the Mapping Memories app by reaching out into the community to learn about the daily lives of those who survived the regime’s atrocities

The project has not only helped students build their production and research skills, but encouraged its young production team to think critically about how Cambodia’s recent past has shaped their contemporary society, according to project manager Chan Muyhong.

“In the context of the rapid development Cambodia is experiencing, subjects of the past and the history, especially from such a tragic period, are not commonly or daily discussed,” Muyhong said.

“There is gap between Khmer Rouge survivors and the younger generation. This project, while helping to widen access to information about Khmer Rouge history, also records testimonies and memories of daily life experience from that period of time, so that these stories can be passed on to next generation,” she said.

For the journalists working on the project, there have been many challenges: sources of information can be scarce, archived photographs are not always accessible, and history experts can be hard to find and interview.

For student Kuoch Masy, who produced a short documentary about the Koh Tang war – a brief battle between the Khmer Rouge and US troops, fought as an attempted rescue of the US crew of the SS Mayaguez – the history of the conflict was completely new to her when she stumbled across it, and required a semester’s worth of intensive research to uncover.

Masy and her teammates set out to preserve the history of this convoluted clash of US and Khmer Rouge forces on Cambodian soil to, in her words, “deliver the message to young people as well as the next generation”. As with all stories shared on the app, the team’s Koh Tang documentary has undergone a thorough fact-checking process by the Documentation Center of Cambodia (DC-Cam), assuring viewers that all data uncovered is historically accurate.

“I hope this project will be well-known to everyone in Cambodia,” Masy said of her work. “I hope this production… will be appreciated, and accepted, especially by the older generation.”

Over the course of the project, several students have reached out to the older members of their community to discuss their not-so-distant pasts of loss and pain – but even as they record the stories for future generations to remember and honour, these aspiring journalists have been confronted with the ethical dilemmas that face all those who report on such sensitive and difficult topics.

While recording her radio piece, “I Lost My Childhood at the French Embassy,” student Seng Socheata was confronted with the sheer emotional weight that those years of loss had laid on a generation of Cambodians. As she interviewed her outspoken protagonist – a French-Cambodian man who had dedicated much of his life to documenting the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge – she was surprised to find her interviewee on the verge of tears as he recounted the last words exchanged with his Cambodian father, who wasn’t permitted to leave the Kingdom when his French family evacuated.

“We [in Cambodia] don’t really talk much… culturally, between parents and kids. We don’t say ‘I love you’,”Socheata explained. “But at this moment, he told me that his dad pulled him aside and told him: ‘I love you’. And this was the first and last time he heard such a thing from his dad.”

There were more questions she wanted to ask, but Socheata ended the interview wondering if her questions were doing more harm than good.

The following semester, as she interviewed a man who worked as an interrogator at the infamous Tuol Sleng detention centre in Phnom Penh, Socheata’s first instinct was to report on the brutal interrogation techniques used by the Khmer Rouge in the camp. But her interviewee expressed concern and fear that sharing his story would cause him to be ostracised by his neighbours – and to lose his livelihood selling bananas.

After a two-hour long interview, Socheata chose to discard the film – and the story.

Digital storytelling

It is one thing to gather the tales of Khmer Rouge survivors for posterity – it is another to gather these stories in a digital format that can easily be downloaded, free of charge, onto any of the millions of smartphones that have flooded the Cambodian market.

“Students – as well as many other Cambodians – are interested in digital technology. They consume media content via smartphones or tablets,” explained Duckstein. “It seemed to us quite obvious to choose a smartphone application as a tool to spread these stories. It’s all about making information accessible.”

The convergence of storytelling and tech is important to aid future students in actively learning about this difficult time in Cambodia’s history and opening a dialogue about Khmer experience, DMC acting director Ung Bun Y said at the launch of the app.

“Dialogue is one of the important tools that help the public learn and reconcile the past with the present,” Bun Y said in his speech on Saturday. “We believe that access to information and stories about Khmer Rouge history is the foremost mechanism for this dialogue to take place.”

The Mapping Memories app is geared toward launching this dialogue between its student journalists and app users, who are given the option of submitting additional information about posted stories via comments sections at each site, and are invited to submit their own stories as well.

With server and production funding to carry the project through the next two years, the DMC plans to continue expanding on the project through 2020, requiring its journalism students to produce five short documentaries and five short podcasts for the app each year. If the DMC is able to find additional funding, future app features will include games and augmented reality features that have the potential to bring the history to life and make stories even more relatable to the app’s tech-savvy users.

Engaging youth

Among the journalism students whose work is now displayed on the app, there is only excitement for what the future may hold – for the app, for Cambodian journalism, and for Khmer history.

Young Odom Rithy, whose articles have already made their way to the pages of various local news outlets, said that this new app is likely to attract more and more users as increasingly high-level content enters the platform.

“I hope this project will pave [the] way for future generations of documentary filmmakers to produce even more interesting historical content in a different light, in the spirit of promoting conversation of hard topics such as the Khmer Rouge history,” he said. “I think the application and website primarily will engage young Cambodians, as it is more accessible in contrast to the traditional platforms where we normally see Khmer Rouge content posted.”

Vann Chansopheakvatey, whose documentary focussed on years’ worth of continued fighting long after the Khmer Rouge regime had fallen, was hopeful about the app’s future.

“So far, we have received a lot of support, so I think we are on the right track,” she said. “I wish this application to be the biggest, most successful centre for saving and documenting Cambodian history… so we can have the younger generation learn, and to not repeat the tragedy.”