Yangon locals ringing in the New Year share the uncommonly heard perspective of what 2017 has been like for the people living within Myanmar’s borders amidst the Rohingya crisis

For a culture known to be under the unflinching control of a military and religious majority, it’s surprising to see young people in Myanmar’s largest city, Yangon, walking freely on the streets sporting brightly coloured mohawks and Dead Kennedys and Misfits T-shirts.

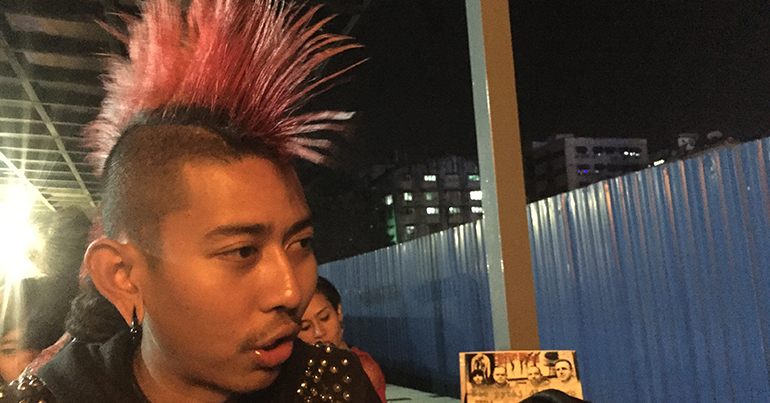

Two nights before Christmas at the Pirate Bar, in a well-heeled district of pricey gastropubs and boutiques east of downtown, a punk/heavy metal/hip-hop showcase was headlined by Myanmar’s most famous punk band, Rebel Riot, whose releases include Puppet Society and Fuck Religious Rules. Its singer and guitarist, Kyaw Thu Win, an original member since the band’s founding during the Saffron Revolution ten years ago, said his band is about more than just the music, that it is a collective working with groups like the Yangon chapter of Food Not Bombs to help build solidarity.

Locals are affable and welcoming. They invite foreigners to sit for coffee, tea and snacks, and proudly host them in their homes to meet family and satisfy curiosity about life overseas. They say they crave peace and stability.

One retired Myanmar navy veteran, 72, who declined to be identified by name, said there is no violence between neighbours of different religions or ethnicities in Yangon. A 39-year-old bicycle taxi driver in neighbouring Dala, across the harbour from downtown Yangon, spoke about how mosques, churches and Buddhist temples worked together after the 2008 cyclone to feed and house people of every persuasion.

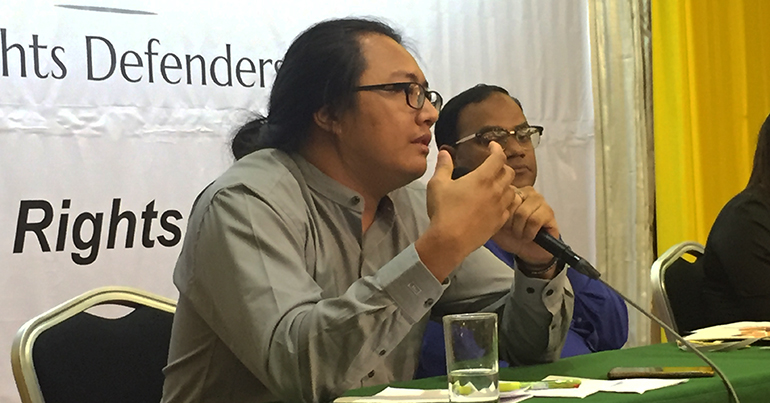

The Human Rights Defenders Forum convened a conference on 19 and 20 December at the Summit Park View Hotel. Under the apparent protection of an international NGO, participants spoke frankly about the violence in Rakhine and the plight of the Rohingya.

But, for the most part, Myanmar citizens and expats in the country choose their words carefully for fear of offending the government. Even Christmas can be cause for concern among some locals.

Days before the Christian holiday, human rights activist Kyaw Soe Aung, 53, a Rohingya Muslim, said he would celebrate Christmas with friends and family in northern Myanmar.

Muslim celebrating Christmas?

“We are all brothers,” said Aung, secretary of the Democracy and Human Rights Party, at its Yangon headquarters.

As he spoke under the office’s harsh fluorescent lights, his eyes were moist. The longtime human rights campaigner said he spent a reduced sentence of five years in prison for his political activities after being sentenced in 1989 for 20 years.

“We are the same,” he said. “It doesn’t matter but that we celebrate each other.”

But the gleaming golden pagoda in the room during any discussion with locals is what is happening in Rakhine State, or what the media is reporting to be happening there.

As Myanmar’s brutal 2017 comes to a close, questions linger about the Southeast Asian nation’s descent into violence. But there are few answers. The sight of Christmas trees, Santa Clauses and North Pole villages in modern shopping malls belies the horrors being denied by the Myanmar government in Rakhine State to the west.

Aung, whose group hosts discussions between leaders of Myanmar’s various religious and ethnic communities, blamed the military government for the anti-Muslim sentiment that he believes has been fuelling the violence. He cited a “golden time” of peaceful democracy between 1948, the year Myanmar won independence from the Britain, and 1962, the year the military took over the country.

Insiders in Myanmar who have spoken with Rohingya survivors and seen the aftermath of violence with their own eyes said they have no idea why Rohingya Muslims are being systematically slaughtered and raped, driven out of their homes, and their villages burned to the ground. No one seems to see any obvious benefit to anyone for the violence that has been documented.

When an anonymous insider was asked who might be orchestrating the anti-Rohingya hatred leading to the mass murder of thousands of innocent civilians – and why – the shrug was chilling.

The stories of the atrocities that the UN investigates, corroborated by eyewitnesses and survivors, offer a glimpse of a hell on earth.

In one village, a Myanmar soldier ripped a baby out of its mother’s arms and flung it into a fire, reported the New York Times. The mother was then gang-raped, and ended that horrific day running for her life through a field, naked and covered in blood. She’d also seen the lives of her mother and three siblings unceremoniously snuffed out.

Survivors have reported seeing soldiers stabbing babies, gang-raping girls and cutting off the heads of children in shocking acts of violence that the Times’s Jeffrey Gettleman described as “flamboyantly brutal, intimate and personal—the kind that is detonated by a long, bitter history of ethnic hatred”.

Muslims in Myanmar

Ethnic, religious and nationalist division has been an emotionally charged issue in Myanmar since the first Muslims arrived here from India a millennium ago. In the 1930s, anti-colonialist sentiment against the British occupiers by the Bamar Buddhist majority got mixed up with anti-foreigner sentiment in general, which translated to anti-Indian/Muslim/Hindu sentiment, explains Francis Wade in his recent book Myanmar’s Enemy Within. The Indian Muslims had become the dominant culture and real estate holders in the then capital of Yangon, which bred resentment.

“This compounded the feeling that not only were livelihoods being drained by foreigners, but that the actual land of Myanmar was being lost, and with it not just the economic worth it carried, but the emotional attachments Bamar had to it,” Wade writes. The native Buddhist majority saw these subcontinent arrivals as not just interlopers, but also subordinates of the British government.

Current anti-Muslim propaganda here is centred on fears of the Islamization of Rakhine State. While Myanmar has been embroiled in civil war for the past 60 years, tensions between Buddhists and Muslims last exploded into violence in 2012—a year after military rule was nominally ended. At that time, Rohingya Muslims were blamed for the gang rape and murder of a 26-year-old woman named Ma Thida Htwe in Rakhine State.

Muslim men were arrested for the crime, but the public wasn’t satisfied. The first act of retaliatory anti-Muslim violence: 300 Buddhists set upon a bus filled with Muslim passengers in Rakhine. The mob dragged ten people off the bus and beat them to death.

Then, as is alleged now, villages were burned and innocent people killed and expelled from their homes.

Nearly 360 Rohingya villages have been partially or completely destroyed since the violence erupted again in late August, according to a 17 December report by Human Rights Watch that analysed satellite imagery. The group says 655,000 Rohingya have fled to neighbouring Bangladesh, leaving about 500,000 remaining in Myanmar.

The anti-Rohingya violence erupted on 25 August when a unit of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army attacked a Myanmar government outpost, killing 11 security forces.

The Myanmar army insists that its backlash has targeted only ‘terrorists’ and not civilians. But a 14 December report by the humanitarian group Medecins Sans Frontieres claimed 6,700 Rohingya civilians have been killed, 700 of them children.

Suu Kyi: ‘fake news’

Interviews with the UN and two local Myanmar human rights campaigners reveal an equally shocking failure to explain why long-simmering ethnic hatreds have degenerated into violence. There doesn’t seem to be any reasoning for any of it, with no group holding the strings for economic or political benefit.

Human rights campaigners, such as Thet Swe Win, said they are hampered in their efforts by complacent citizens and officials who are flat out in denial of the violence and by police who have threatened to arrest those who report crimes against Muslim minorities. The much-criticised Myanmar leader Aung San Suu Kyi has recently begun to parrot US President Donald Trump, calling reports of atrocities “fake news”.

The state-run media has framed the issue as a battle against nefarious forces. A local insider who, like others interviewed for this article, wished to remain anonymous for fear of government retaliation, said that if you compare the international news to debate within Myanmar on the Rohingya issue, you get two very different perspectives

“The United Nations believes in freedom of speech and expression as well as the right to information by media,” said Aye Win, national information officer of the United Nations Information Centre in Yangon, in a prepared statement. “As is mentioned in the Advisory Commission on Rakhine State’s Final Report, there is ‘a clash of narratives’ on Rakhine. “These narratives,” the statement continues, “are often exclusive and irreconcilable, ignoring the fears and grievances of the other community.”

The international community’s hands are tied, continued the anonymous source, leaving local human rights activists to face a challenge in changing minds—and staying out of government crosshairs.

‘Rohingya literally banned’

The local media doesn’t use the term Rohingya at all. Instead, the national debate centres on the military fighting terrorism, illegal immigration and citizenship. International media, meanwhile, frame these events as a human rights disaster and even genocide.

“You can’t find anything about the Rohingya issue in our local media,” said Thet Swe Win, founder of the Center For Youth & Social Harmony. “They can’t use the word Rohingya. They call it Bengali. [One Myanmar publication] used to use the word Rohingya, but they were warned by the authorities not to use it. So the word Rohingya is literally banned here.”

Win is a rare Myanmar Buddhist activist who’s bold enough to openly speak out against anti-Muslim violence and bigotry. He took some heat online after he said in a November interview with Southeast Asia Globe that the Rohingya are not terrorists. He was called a “maggot” he said, as the article was shared hundreds of times. He said some comments implied that people might be trying to find out where he lived.

Win and his group are awaiting government approval to launch a live telephone hotline that people can call if they become aware of any stirrings of violence.

‘Silence is violence’

Rebel Riot’s frontman, Kyaw Thu Win, spoke with optimism about the country he loves between sets at the Pirate Bar just before Christmas. It was a rare moment when the young punk with a red mohawk wasn’t surrounded by cigarette-smoking girls and boys in studded leather jackets and shredded fishnets.

“I really hate people killing each other, because we are all human,” he said. “We should be kind to each other, we should share with each other. But with the Rohingya situation, people are afraid of each other, they don’t trust each other, they are full of fear of each other. People are ready for violence, people are ready to fight.

“I believe silence is violence.”

Related reading:

- How peace for the Rohingya can begin with recognising Rakhine State’s past grievances

- Why this pro-Rohingya Buddhist is speaking out against his country’s government

- Reuters journalists covering clampdown on Rohingya in Myanmar arrested

- Pope uses ‘Rohingya’ while meeting a group of refugees in Bangladesh