From Yangon to the mountains of Shan state, resistance to the February 1 military coup has pulled together a diverse coalition of Myanmar’s many ethnic groups.

While attention is focused on protest movements against the military in urban centres, demonstrators in Myanmar’s major ethnic states have also been gathering in opposition, hoisting flags bearing traditional symbolism in a spectrum of colours.

Long held outside the national political mainstream, the demands of Myanmar’s ethnic groups go beyond the fall of the military regime – they are calling for federal democratic rights denied to them under both six decades of previous military rule and five years of governance by the popularly elected National League for Democracy (NLD).

Members of Myanmar’s ethnic minorities make up around 35% of the country’s population, dwelling mainly in borderlands and mountainous regions. Despite their political support for the NLD, many say they have not yet seen the relief from poverty, isolation and armed conflict they’d hoped for after the electoral victory of the party under party leader and former State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi.

Anti-coup protestors from minority states say they’re demonstrating for a true federal democracy, including a new constitution that would better protect and promote ethnic rights.

Vantha Hlei, a 28-year-old Chin media worker living in the Chin state capital of Hakha, said the NLD government didn’t do enough to develop her state, the country’s poorest, while in power. She told the Globe she’s protested almost every day since the coup, but more action is also needed.

“Apart from protesting, I talk with my old classmates and friends from abroad and tell them about the situation on the ground,” Vantha Hlei said. “I try my level best to find every possible way to let the international community know about how much the people in Myanmar are bitterly against military coup.”

Chin state is majority Christian, located on Myanmar’s mountainous northwestern border with India. The state is home to fewer than half a million people, among them nearly 50 distinctive sub-groups with differing languages and cultural traditions. In the southern Chin town of Kanpetlet, women who demonstrated on February 23 donned markings on their faces in the style of the traditional tattoos of various regional tribes.

This kind of creative protest is one way that ethnic groups are at once showcasing their diverse histories, while also calling for greater targeted reforms within their distinct states.

“If the military cannot be kicked out of the government, human rights violations of the past will be repeated. If the military is in power, Chin State will not be able to get out from the pit of poverty it is in,” Vantha Hlei said.

Vantha says she hopes for a nation that reflects the Panglong Agreement of 1947. For her and others protesting in ethnic-majority areas, that agreement looks today like the blueprint for a fairer state. The Panglong document was penned by ethnic leaders and General Aung San, father of now-imprisoned Suu Kyi as well as Myanmar’s independence leader against British rule. The agreement guaranteed full autonomy and citizens’ rights for Myanmar’s major ethnic groups, but was effectively dissolved during the 1962 coup led by military commander Ne Win.

Though the military relinquished some of its power in the 2011 elections and allowed Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD to form a government in 2015 after winning a landslide victory, Vantha Hlei says the government still failed to protect minority rights due in part to the military-drafted 2008 Constitution.

“Chin people have continuously suffered from denials of identity, religion, culture and literature under the military governments since 1962. These governments tried to root out our religion, culture and literature, and to assimilate us into Burmese cultural norms.”

Nationwide, following the February 1 coup, Myanmar’s military has launched a series of violent crackdowns on groups gathering in protest, resulting in over 2,000 arrests and at least 130 deaths. Among those in detention are the country’s State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Myint, politicians, journalists, activists and artists.

Security forces have used water cannons, tear gas, live and rubber bullets and stun grenades on peaceful protesters and beat medical volunteers. Yet, despite facing increasingly brutal actions and the constant fear of night raids and arrests, thousands of ethnic minorities and Burmese citizens alike continue taking to the streets.

Across the country, youths of different ethnicities have come out in a show of unprecedented unity. Representing this solidarity, the General Strike Committee of Nationalities (GSCN) was established on February 11 as a multi-ethnic demonstration group by a group of 16 Karen, Chin, Kachin and Rakhine youths. Since then, representatives of 29 additional ethnic groups have joined the protest alliance.

Initially, its members walked through Yangon holding flags of the groups they were representing. But near the end of February, the regional outfits were replaced by gas masks, goggles and homemade shields, to protect demonstrators from the military’s violent crackdown efforts. Security forces have already arrested at least 17 members of the group for participation in the protests.

“We have a system of collective leadership and we are working on four objectives: to end the dictatorship, abolish the 2008 constitution, build a near-federal democratic union and to free all those unjustly detained,” a GSCN representative told the Globe, asking to go unnamed.

The majority of my community still live under fear. They do not dare to raise their voice. The village leader is Ta’ang but he doesn’t want more trouble

But while protests gain momentum in Yangon, fear keeps some indoors, demonstrating their opposition in less conspicuous ways. This has been the case in conflict-torn northern Shan State where many members of the Ta-ang ethnic minority have been protesting from home. But even this can be dangerous.

The Ta-ang, or ‘Palaung’ in Burmese, have an estimated population of half a million living in Myanmar, China and Thailand. On a few occasions in Namhsan, the capital of Palaung Self-Administered Zone, hundreds have filed through streets since the coup in narrow streams donning the group’s green and red flags and calling for the military to step down.

But a deep-running fear of the military, resulting from decades of armed conflict between the Ta’ang National Liberation Army and Myanmar’s military, keeps many silent.

“The majority of my community still live under fear. They do not dare to raise their voice,” a young Ta’ang entrepreneur told the Globe, adding that he’d heard the village leader had asked some community members not to bang pots and pans, a common form of protest in Myanmar today. “The village leader is Ta’ang but he doesn’t want more trouble.”

Still, local disapproval can only go so far.

“[The village leader] didn’t speak to me directly so I still bang pots every night,” the entrepreneur said.

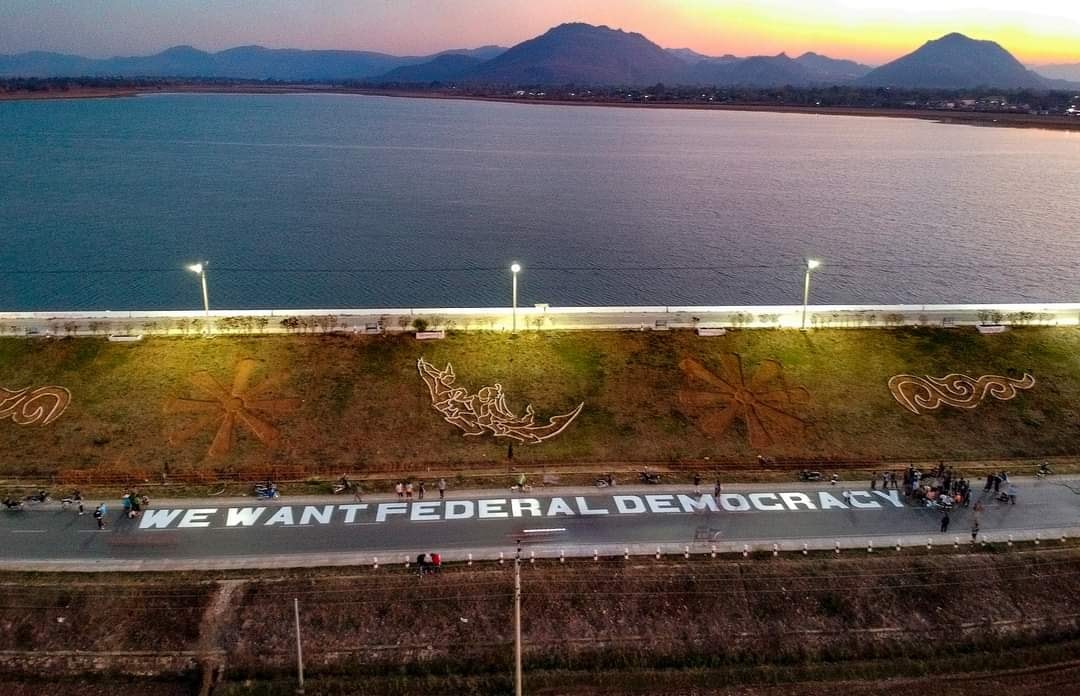

Other low-intensity demonstrations have sprouted across the country. Graffiti and road murals have become a common sight, with dozens of slogans in metre-long letters painted across roads in English, crying out “Respect Our Votes”, “Federal Democracy,” and “No Dictatorship”.

When these first started popping up in mid-February, they were quickly erased overnight, but there are now so many around the cities and towns that authorities no longer try to remove them: a small victory for the people, says Theik Soe Aung, a 27-year-old activist from Loikaw, the Kayah State capital.

Kayah State on the western border with Thailand is the country’s smallest state and home to the Karenni people and a multitude of smaller ethnic groups. Theik Soe Aung has been organising road paintings in his home state.

“NLD supporters want to write ‘We Want Democracy’ on the road but most of the young ethnic people’s vision is clear – they want not only democracy, but federal democracy,” he told the Globe.

Theik Soe Aung said many Karenni people were unhappy with the NLD’s centralised rule, feeling like their voices and opinions were totally neglected during its tenure. A prime example of this, he said, was the installation of a bronze statue of General Aung San in a park in Loikaw, the state’s capital, in 2018.

Karenni people do not identify with the Burmese general, unlike the majority Bamar people, and protested the installation. Then, as is happening now, their protests were quashed by a heavy police response, including batons and tasers.

The military already took away my childhood. So I am out protesting on the streets of Yangon every day.

Similar tactics have been used in Kayin (Karen) state, which borders Kayah on its southern border and is populated by the Karen people, a nation of 3.5 million people within Myanmar, plus more than 1 million who have relocated to neighbouring Thailand and elsewhere in the world. Many left their homeland to flee a brutal, seven-decade civil war, pitting the Myanmar military against the Karen National Liberation Army, an ethnic armed organisation, and its breakaway group, the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army.

“Since I was born, I have been running for my life,” said Nan Eh Tue, an ethnic Karen now living in Yangon.

From the age of three years old, her family often had to move to avoid conflict before fleeing to Nu Po refugee camp on the Thai side of the border at the age of 14.

Though she now lives in cosmopolitan Yangon, Nan Eh Tue has heard the protests back in Kayin State have been bolstered by large groups, including the young and “very poor”, travelling from smaller villages to urban centres to protest military rule.

The commitment to protest speaks to what was lost in the state through decades of violence – and what might be gained in a more democratic future.

“The military already took away my childhood,” Nan Eh Tue said. “So I am out protesting on the streets of Yangon every day.”

For the protection of interviewees, some names have been changed at their request.