Reuben Lim is a Singaporean citizen and former international civil servant. He holds a BA in European Studies from the National University of Singapore and is currently pursuing an MSc in Management at Trinity College Dublin. While the Globe takes the utmost care to publish accurate information, by the nature of these first-hand accounts we are unable to independently verify their accuracy.

In late March I developed an innocuous cough – one so mild and intermittent that I quickly wrote it off as something minor and certainly not the coronavirus. Two days later, the frequency of the coughing episodes had increased but at no point would I have described them as “persistent”.

By then, I had already been self-isolating at home for six days under Singapore’s government-mandated Stay-Home Notice. A surge of infections had been detected among Singaporeans returning from abroad, particularly Europe and the US.

Described as a second wave, it kept people on edge and authorities laid a series of measures to prevent spread to the wider community. To ensure that I never left my home, I was asked to report my GPS location as well as take photos of my surroundings several times a day.

Having recently returned from Ireland which had less than a thousand Covid-19 cases the day I left, I thought that the chances of me contracting the virus were extremely low, particularly as I had taken adequate precautions during my time in Dublin and on the journey back. Regardless, the cough was enough to be a cause of concern for my family.

After some persuasion from them, I called a dedicated hotline for returnees which set off the public health machinery. I was instructed to visit a nearby GP to get my symptoms checked out. After a quick examination, the doctor felt that the likelihood of me having the coronavirus was low. Nevertheless, I was referred to the National Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCID) for a swab test on the very same day as returnees were considered a “high-risk” group.

Given the mild symptoms I had presented, I was pleasantly surprised at how easy it was to get access to a test. This was not the case in Europe where I observed that only those with serious symptoms had access to tests.

Confident that I was negative, I happily went through the motions. “At least I could give my family some peace of mind,” I told myself. The entire process at NCID involved an assessment by a doctor, an x-ray and a nasal swab – all of which were completed within a short span of 45 minutes.

Because my x-ray did not show signs of pneumonia, I was instructed to wait at home for the test results. A call would be made if I tested positive while a text would be sent if it was negative. The efficiency observed at NCID was impressive and also gave me an interesting first-hand glimpse into the much-lauded “gold standard” coronavirus response I had read about in the news.

The next morning, a call from unfamiliar number flashed on my screen. It was at that very moment that I knew something was wrong.

For almost a week, I had nonchalantly interacted with my family without taking self-isolation recommendations seriously. I was mortified at the thought that I could have very well passed on the virus to them

True enough, the other person on the line was a representative from the Ministry of Health. She called to inform me that I had tested positive for Covid-19 and that an ambulance had been dispatched to bring me to hospital.

My heart raced upon hearing the news. For almost a week, I had nonchalantly interacted with my family without taking self-isolation recommendations seriously. I was mortified at the thought that I could have very well passed on the virus to them.

The ambulance arrived soon after and brought me back to NCID where I was to be isolated and treated. I have to admit that the experience was rather exhilarating. This was the first time in my life that I was transported in an ambulance and warded at a hospital.

I was placed in a luxurious two person ward that had the trappings of a hotel, including an en-suite shower and a fine view. I was quickly attended to by two doctors who explained that I will be warded for a few days as there was a chance that symptoms could worsen.

Blood tests were conducted (there are markers to look out for indicating susceptibility to worsening symptoms) and for the rest of the afternoon, a flurry of calls from various health ministry official came in.

In particular, I spent about 30 minutes with an epidemiologist interested in details of activities and whereabouts over the past two weeks. This was for contact-tracing purposes which has been credited for helping authorities stay one step of the virus and keeping the curve flat.

Another official called to reassure me that close contacts a.k.a. my family will be well taken-care of, and indeed they were. My parents were brought in to be examined and tested the very same day which thankfully came back negative.

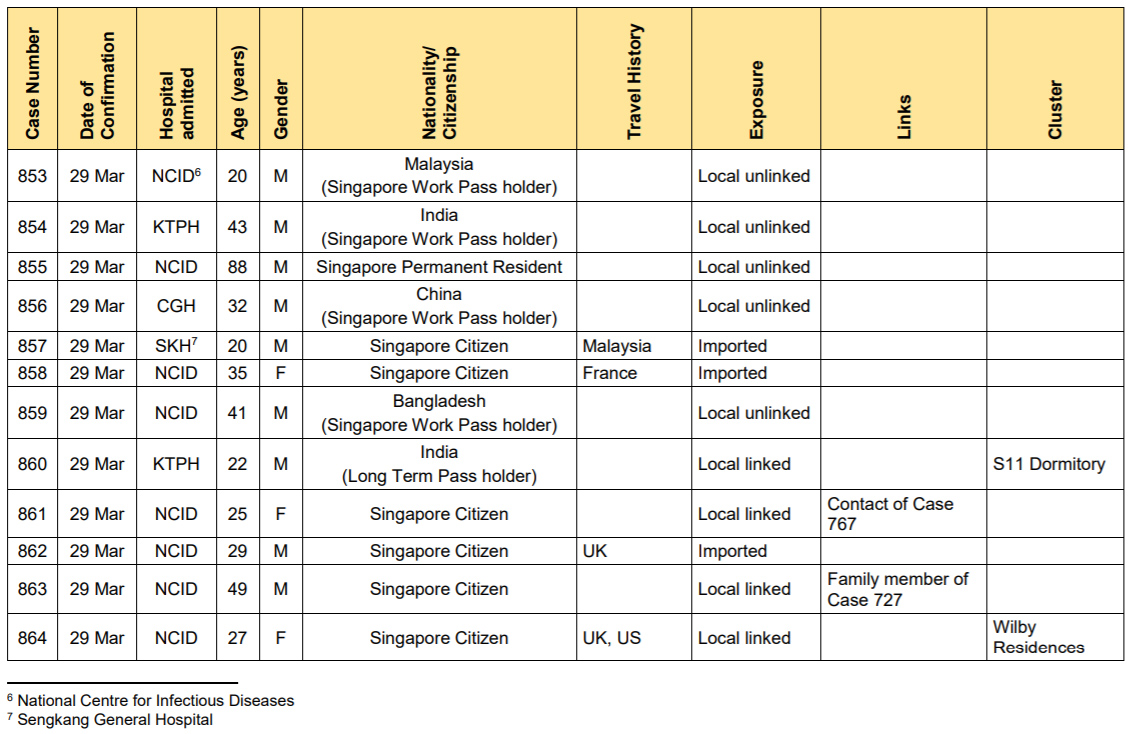

Nevertheless, they were served with a 14-day Quarantine Order. The National Environment Agency also visited our home to deliver cleaning supplies and disinfect the common areas of the building. We genuinely felt looked after. When evening came round, the daily press release from the Ministry of Health, known for containing an unusual depth of details, was released and lo and behold, I saw myself officially recorded as Case 862.

The next few days proved to be a great learning experience for me about the virus and the government’s response. Being able to have access to and speak with doctors on a daily basis allowed me to glean off medical knowledge first-hand and clarify conflicting information I had come across in the media, such as the risk of reinfection.

I was made aware that it was common for young adults to present only one symptom and that short-term immunity of up to a year is possible after recovery. It also became apparent to me that Singapore’s approach to tackling the virus deviated from countries elsewhere and adapted to local conditions.

Rather than advising the mildly sick to self-isolate and recover at home, authorities here prefer to hive off all of the infected and isolate them from the rest of the community until they’ve fully recovered. Proper self-isolation is apparently very hard to achieve, particularly when most households live in apartments.

In addition, NCID is a new state of the art hospital that opened late last year and I was very privileged to be among the first to be warded there. A lot of thought had clearly went into the design of the hospital and the widespread use of modern technology is equally impressive. Negative pressure rooms were the norm, iPads, scanners and QR codes were used instead of pen and paper while doctors communicated with patients via intercom to reduce unnecessary contact.

Fortunately, my stay at NCID turned out to be short. My symptoms did not worsen and my cough had disappeared by day four after admission. The infection had been limited to my upper respiratory tract and had not progressed further into my lungs.

I was lucky – every other patient I interacted with, including those who were of the same age group as me, had more severe symptoms that required hospitalisation of a week and more. This goes to show how unpredictable the virus can be and the varying effects it can have on people regardless of their age.

To make room for new patients, I was transferred out on day six to a convalescence centre known as a Community Isolation Facility where I would stay until I have fully recovered. This facility turned out to be another luxurious experience – it was essentially a holiday resort by the beach that had been booked out by the government for the clinically well to recover.

While everyone had to stay within the confines of their rooms, they were big in size and came balconies that allowed us to enjoy fresh air. Food, water and all other essentials were also provided on a daily basis. No doctors were stationed at the facility but representatives from the health ministry would call three times a day to check on each person’s condition. Nurses would also come round every four to five days to collect nasal swabs for testing.

Two negative swabs were needed in order to be discharged and again, I lucked out. After five days at the facility, my first swab test came back negative indicating that I was no longer infectious. The second swab test occurred a day after and also came back negative which came as a relief.

12 days after I was first diagnosed, I was finally cleared of the virus and officially discharged! This was a relatively short time for recovery as the virus can linger in the body for as long as a month.

From the point where overseas students were advised to return home until the end of my treatment, I have consistently felt reassured that Singapore has me and my family’s welfare at heart

Today, two weeks after being discharged, I returned out NCID again for a follow-up consultation. I am very happy to share that the doctors have given me a clean bill of health and have also requested that I donate my plasma which I am more than happy to do.

The entire experience has been no less than surreal. I am very thankful that my brush with Covid-19 was the mildest of the mild. Apparently, my immune system is a lot stronger than I thought! In addition, the amount of care I received despite my mild symptoms was unparalleled with what I’ve experienced elsewhere. Frontline workers truly are heroes.

A lot has changed since I was discharged. Singapore is now under a partial lockdown which was extended until 1 June. This as case numbers have skyrocketed, particularly as large clusters have been detected among vulnerable migrant populations residing in dormitories.

Capacity constraints means that not everyone is able to recover in the comfort of a beach resort and a new bare-bones convalescence centre has been set up inside the halls of the Singapore Expo. Whatever feel good feelings about Singapore’s earlier “gold standard” success has also largely dissipated.

Yet I remain optimistic that Singapore will successfully weather through the crisis. Despite recent missteps, the government continues to take decisive action and remains hell-bent on containing the virus.

From the point where overseas students were advised to return home until the end of my treatment, I have consistently felt reassured that Singapore has me and my family’s welfare at heart. If my observations and experience with the excellent healthcare system here are anything to go by, I believe that those who need access to testing and treatment will continue to get it, albeit in less luxurious circumstances.

I am also very pleased to read that migrants, which now make up the overwhelming majority of cases, are receiving the same free high-quality care and treatment that Singaporeans are entitled to. As a person with an interest in migration affairs, this is very heartwarming to see.

Plenty of reasons to be happy about being back home!

This story is part of the Globe’s Tales of the Pandemic series, a collection of personal essays from across Southeast Asia called published each Monday covering different aspects of life during this unprecedented time in human history. All of these Covid-19 stories can be found here. If you’d like to contribute a personal essay of your own, please email your story of roughly 1,000 words to a.mccready@globemediaasia.com.