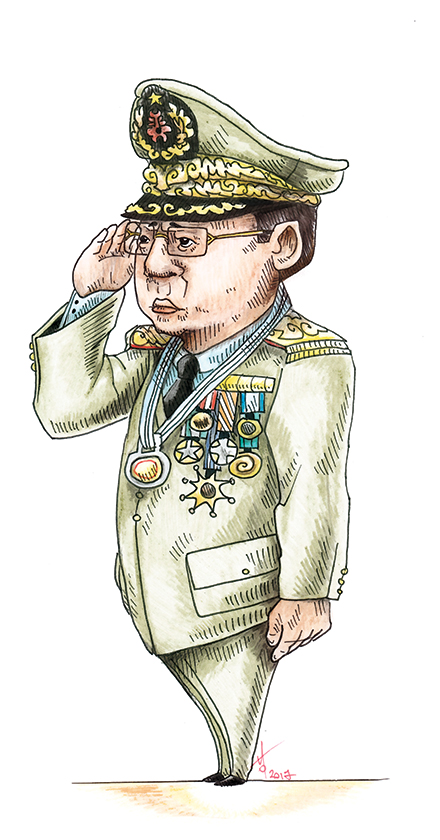

Who is he?

The commander-in-chief of the Myanmar armed forces – known locally as the tatmadaw – senior general Min Aung Hlaing rose through the ranks at the height of the military’s fierce campaign of suppression against the nation’s armed ethnic insurgencies. For more than three decades, the military has employed its ‘Four Cuts’ policy of systematic terror and forced relocation – inspired by earlier British campaigns against Myanmar’s communists – to strip rebel groups of funding, food, intelligence and recruits.

Why is he in the news?

Aung Hlaing has been the chief architect of the intense counter-insurgency campaign against Rakhine State’s Rohingya communities – a crackdown that has driven more than 600,000 of the Muslim minority across the border to Bangladesh. And despite the international condemnation slowly mounting against state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, the general has shared little of the blame for the bloodshed – even receiving an audience with Pope Francis during the Catholic church leader’s visit in November.

How did he grow so powerful?

Although the tatmadaw-drafted constitution of 2008 paved the way for a slow transition to civilian government, the document enshrined a great deal of autonomy and authority within military hands. As supreme commander of all armed forces, Aung Hlaing appoints one quarter of all parliamentary seats and commands the police, border guards and the wider military through his control over the home affairs, defence and border affairs ministries. Most importantly, his authority over two massive holding companies and a vast network of patronage allows the military virtually complete economic self-reliance.

What does he stand to gain?

K. Yhome, author of Myanmar: Can the Generals Resist Change? said it was possible the general was preparing for a presidential campaign in the upcoming 2020 election, having seen his chances of the presidency stripped away by Suu Kyi’s 2015 landslide. “If the military today is doing what they’re doing in Rakhine State or in other ethnic minority areas purely with the political ambition of this man to become the next president – I don’t have the answer to that, but that would be a very dangerous direction for this country to go down,” he said.

Will it work?

While he emphasised that the campaign still had its detractors within the nation, Yhome said that the military had long used the threat of Islamist terror rising within the Rohingya to portray itself as the last bastion between the Buddhist majority and an insidious assault on Myanmar’s culture and values. “The regime has been able to create a very systematic division between the majority Burmans and the ‘others’ – which includes other ethnic minority communities and the Rohingya,” he said. “I think… there is a huge [number of] Burman Buddhists that believe that what Min Aung Hlaing and the tatmadaw is doing is for the good of the Burman society.”