Yong Han Poh is a senior at Harvard University in the US studying Anthropology and East Asian Studies. She has written for The Diplomat, the Singapore Policy Journal, and the ArtsEquator. While the Globe takes the utmost care to publish accurate information, by the nature of these first-hand accounts we are unable to independently verify the accuracy of the details contained within them.

On March 10, a Tuesday morning, two days before my senior thesis was due, my roommate knocks loudly on my door when I am half asleep. “Han,” she says, half-crying as she enters my room. “Wake up, they’re cancelling Harvard.”

Still half-asleep, I open my inbox to find a barrage of emails, confirming what she said. The President of Harvard University, Larry Bacow, had written to inform us that all undergraduates were to leave campus by Sunday, March 15, 5pm.

Over the course of the next 24 hours, my phone explodes. Friends take to social media to express their horror, grief, and outrage. Students fret over what this means for international students who might not be able to leave at such short notice, for visa requirements, or for safety reasons, particularly for those who come from Level 3 Advisory countries (“avoid nonessential travel”), or for students with vulnerable living situations. Professors are equally confused about how to conduct classes via app Zoom, especially when coordinating across seven different time zones.

Harvard’s eviction notice makes international headlines, and someone from Channel News Asia asks to interview me. After the interview, she texts, “It just seems so overbearing”, referencing the university’s policy. I don’t know what to respond.

Several days later, I watched as news reports flood in. Boston had its first cluster of cases tied to a pharmaceutical conference, and it looked like Massachusetts was headed for Italy levels in the next two weeks if nothing was done to contain the crisis.

It seemed that initial accusations about the eviction policy being a liability issue rather than public health risk seemed unfair. The virus posed a looming threat – not just to Harvard, or Massachusetts, or even the United States, but to the world.

Suddenly, fretting about finishing up senior year and attending commencement seemed petulant and childish. There were frontline workers dying in Italy, and doctors had to triage between patients as hospitals reached full capacity.

Within a few days, life as I knew it had been completely upended. I spent the final five days and ten hours since the eviction notice submitting my thesis, booking flights, packing four years worth of material objects into two-and-a-half suitcases, and spending my last few moments on campus with my best friends.

On Sunday, I bid Harvard and the US farewell as I headed home for Singapore, about to start a fourteen-day (self-imposed) quarantine.

The oddest part about living through a pandemic is the strange mix of emergency and normalcy. In quarantine, I receive the world through my phone in the confines of my bedroom. Every few minutes, I scroll listlessly through my Facebook feed as it updates me on the crisis: the UK reverses their botched plan for “herd immunity”, Trump dubs Covid-19 a “Chinese” virus. Someone has created an infographic that tracks the number of reported cases and deaths live; another government unit develops an app for contact tracing.

At the same time, my mother, who is overjoyed at me returning, cooks all my favourite dishes (fried tomato-egg, and mentaiko salmon), joking about how her daily routine is already the quarantine life.

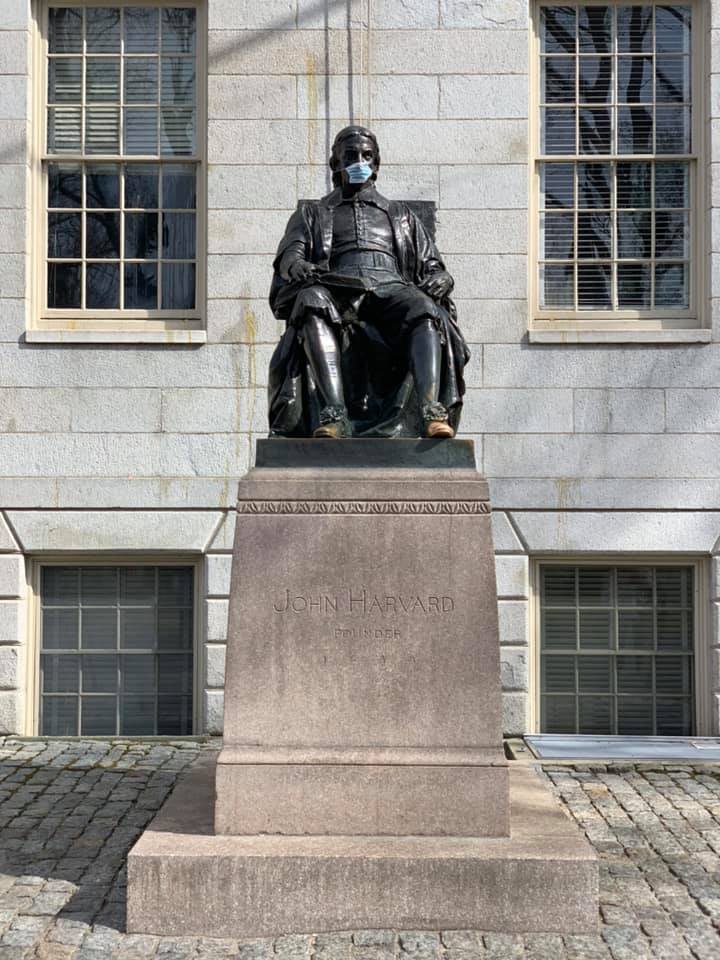

“At least you will have an interesting story to tell your grandkids,” my mother comforts me, as I grieve about the abrupt end to my semester at Harvard, and my stay in the United States. Amongst my cohort mates, there is a sense of living through history, or at least, history-making. As the former Dean of Students Archie C. Epps III infamously said, “Harvard University will close only for an act of God, such as the end of the world.”

And it does seem like the end of the world, at least, according to the increasingly dire headlines every day. The US stock market is falling faster than during the Wall Street crash, and analysts anticipate the worst financial crisis since 1929. Airlines seem to be headed for bankruptcy unless governments step in with massive bailouts, and most employees have already been asked to take unpaid leave. Italy tops the 10,000th death toll, despite its long lockdown.

Boredom is a small price to pay, and I am grateful to have shelter and food at hand. Others have not been so lucky: some Malaysians have had to sleep rough following a sudden lockdown; in California, the large homeless population has nowhere to self-isolate

Still, I take comfort in the fact that at the very least, Singapore’s leaders seem to know what they are doing. In contrast to Trump’s confused Oval Office speech that inspired unease rather than confidence, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong oozed calm and quiet confidence as he addressed the nation in three languages (the meme community lapped it all up; PM Lee’s trademark pink shirts included.) In quarantine, I watch live videos of Minister Lawrence Wong delivering daily updates of the coronavirus situation, and try to avoid being too smug about having good government.

Every few days, a rotating official from the Ministry of Health calls me. “We are calling you because you have recently returned from overseas,” the official clarifies, “so we are here to check up on your health and well-being. Have you been experiencing any symptoms?” I have not been issued an official Stay Home Notice (SHN), but I imagine someone trawled through the Immigration & Checkpoints Authority’s (ICA) records for a list of recent returnees from the United States, a burgeoning hotspot.

A remarkable effort, I silently applaud, and marvel at the army of volunteers recruited for the sole purpose of calling returnees. “This is the deep state,” I text my friend, simultaneously reassured and troubled by the surveillance practices at play. “At least she asked you how you are,” he jokes. “This is the deep, but caring state.”

By day five of quarantine, I have already played fifty-seven games of Sudoku (Expert level), binged watch an entire series of a Chinese fantasy drama (admittedly fast-forwarding through the boring bits), attempted to memorise the Three Character Classic (三字经) and stalked my (fictive) crush via multiple social media platforms.

Inspired by the large swaths of people performing live acapella concerts and initiating fourteen-day drawing challenges, I resume work on my novel (already twice-abandoned). After all, William Shakespeare wrote his best plays during the plague. You could be Shakespeare, I try to inspire myself, before being distracted by Zoom Memes for Self Quaranteens.

There is nothing to structure my day, apart from meal times. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner take on disproportionate heights of fantasy – I eagerly anticipate each meal, imagining the countless possibilities at hand. I snap a photo of my mother’s cooking and upload it onto Instagram; it has almost become a ritual, a ritual offering to my friends, most of whom are also on (self-imposed) SHNs. We take gratification in collective isolation; somehow, that it makes it less alienating.

In between meals, I continue to scroll through listlessly on social media, watching people upload ab workout videos as I binge on matcha wafers. The world is on fire, but someone tells me to “take deep breaths and meditate”. I grudgingly comply, before remembering I have a class on Zoom in ten minutes. I decide I should wear some pants, just in case. The professor begins the session with a reminder about final paper deadlines and exams. The world may be ending, but I still have to submit my essays.

Boredom is a small price to pay, and I am grateful to have shelter and food at hand. Others have not been so lucky: some Malaysians have had to sleep rough following a sudden lockdown; in California, the large homeless population has nowhere to self-isolate.

For now, life goes on; at least, a mutated version of life as we know it – a Black Mirror-esque techno-dystopian reality where we work, socialise, and even date through virtual screens. Our sense of reality may be distorted by the ever-expanding news, most of them dire, about new cases and mortalities; our daily rhythms interrupted by the exigencies of flattening the curve.

These will all no doubt be dissected by future academics looking back at the crisis. The virus has already transformed much of modern life: once-bustling cities – designed for density – have now become barren ghost towns. Gestures of intimacy – a hug, a handshake, a kiss on the cheek – are now abandoned or at least radically transformed (elbow bump, anyone?)

Elsewhere, assumptions about remote work are shifting, as employers are forced to contend with social distancing policies. Similarly, universities are forced to re-evaluate their role in higher education and the value of on-campus teaching as colleges worldwide contend with virtual lessons.

But we may need some distance before we can properly excavate this pandemic from history, and take stock of the damage done – not just in terms of bodies, but also public trust in governments and institutions, our social fabric, and individual sanity. Right now though, it is still too early to write a history or sociology of the pandemic.

The situation is still rapidly evolving with no end in sight, at least, in most countries outside of China, which has reported no new local infections on March 18. When that moment comes, we will have plenty of reckoning to do, plenty of systems to fix and perhaps plenty of officials to boot.

Till then, we can only take refuge in collective strength, through the solidarity of strangers, to keep our spirits up. As individuals, our ability to help others (particularly if quarantined) may be limited, but we can still salvage some sense of agency in these trying times. Check in with family and friends who might be too embarrassed to ask for help. Donate to local soup kitchens and homeless shelters that serve critical vulnerable populations who may not be equipped to “shelter-in-place”.

And maybe write an article to relieve the tedium of self-isolation.

This story is part of the Globe’s collection of personal essays from across Southeast Asia called Tales of the Pandemic. Published each Monday and covering different aspects of life during this unprecedented time in human history, all of these Covid-19 personal essays can be found here. If you’d like to contribute a personal essay of your own, please email your story of roughly 1,000 words, preferably with images, to a.mccready@globemediaasia.com with the subject “Covid-19 personal essay”.