Memories of a refugee childhood

In 1991, sixteen Khmer families from Cambodian refugee camps received asylum in the Netherlands. Chhay Lin Lim's family was among them. Lin Lim was born in the camp in 1986, now he's sharing his early memories of life living as a refugee

Chhay Lin Lim, former refugee and the author of this piece, is today a blockchain lecturer at Saxion University in the Netherlands. He has authored the Blockchain Basics Book, which is currently taught in universities in the Netherlands.

I understand that my story is just one small, but essential part of my family’s overall journey for safety from the civil war (1967-1975), Khmer Rouge (1975-1979) regime, and the subsequent Vietnamese occupation. According to some estimates, 2 million out of 8 million people died during this long period. This figure has been contested many times. I don’t think anyone knows how many people have actually died, but if I look at the family members of my parents’ households: 40% from my mum’s side died and 25% from my dad’s side.

Khao I Dang, the refugee camp where I was born

My parents were forced to work in labour camps in the countryside in Battambang by the Khmer Rouge. They eventually met each other while fleeing from Battambang to the Thai border when the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia. As with most fleeing Cambodians, my parents decided to get together – not out of love, but more out of the need and desire to share their hardships. This was after all, a months-long journey through the heart of the Cambodian jungle in which my father lost his father, the granddad I never came to know. My mother lost her brother and her father. As my mother was separated from her brother early on during the Khmer Rouge regime and never witnessed his death, she had always held hope that one day she would find him again.

My parents’ long journey towards Thailand brought them to the Sa Kaeo camp which was the first organised refugee camp that opened in 1979. Within just eight days, the refugee population grew to 30,000. The camp eventually closed down half a year later, because of unfavourable conditions. The drainage in the campsite was for example so poor that several refugees, too weak to lift their heads, drowned from a flood as they laid on the floor in tents made of plastic sheets.

One month after the opening of Sa Kaeo, the Khao I Dang camp was opened and many people were repatriated into Khao I Dang. My parents eventually ended up there as well.

Khao I Dang was a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodian border where I was born. It was a bamboo village with dirt roads, barbed wire, and armed guards. Within just five months, the camp’s population reached 160,000. Population wise, this would make the camp the 11th largest municipality in the Netherlands.

Although the camp gave us more safety, violence and theft ran rampant.

Religion and death

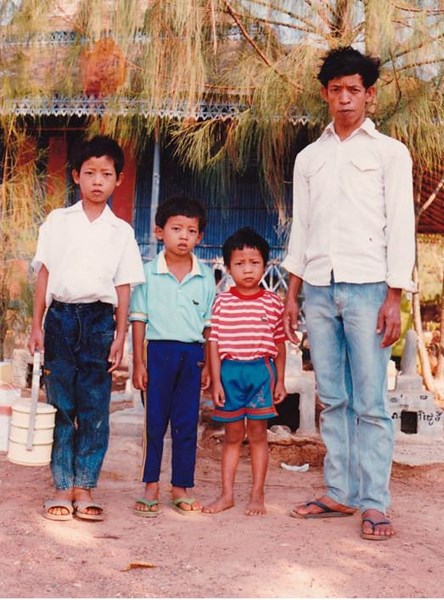

People continued their religious activities and some houses were transformed into places for Buddhist ceremonies. In this picture you see my two brothers, my father, and I wearing our best clothes. We just came back from a visit to a local ‘temple’. The husband of my aunty, who had just been allowed to find refuge in Australia, had recently died in the camp.

Behind me is a grave of him. My father hired a photographer to take this picture so that he could send it to my aunty. I am the one barefooted.

The hospital

My father worked at the hospital. The hospital was a large hall with beds placed next to each other. I remember that I visited the hospital where I was given a doctor’s gloves to play with. I would blow it and enjoy a child’s kick out of it.

The night raids

I remember that during some nights, rebels with guns would raid people’s houses to steal their belongings. Often, the word about night raids spread faster than the rebels themselves, and so most of the times we were warned before the rebels reached us. I remember very well one incident when we did not flee early enough.

My brothers and I ran after my father, while my mother took my baby sister in her arms to flee in separate directions. My father brought us into a nearby canal to hide there. When the Thai patrolling soldiers within the camp arrived at the scene, shooting between the two groups erupted. When I think back to this moment, I can still clearly feel the fear I had. I wanted to cry, but my father put his hands tightly on my mouth so that I would not make any sound. We then fled to the hospital where my father was working, and stayed there during the night. We were too afraid to go back home, and waited until the next morning.

In another incident, our neighbours were too late to flee and somehow for reasons unknown, a rebel threw a hand grenade inside their little home that killed the whole family.

Playing hooky

Despite the violence and misery, people tried to rebuild their normal lives. I went to kindergarten and remember so well one incident that I played hooky.

I was four years old and walking to school by myself, I stopped and decided to return home to my mother’s small shop. This is an incident that I am personally extremely proud of. As long as I can remember, I have always detested school. I hated to sit still and to be told what to do and what not to do. I took this attitude with me to the Netherlands, and still today I am very critical of schooling. My mother, a soft young woman, let me stay with her at the shop. But then my father came by, got angry with me, and spanked me for not going to school. Until this day I still don’t think that I did anything wrong.

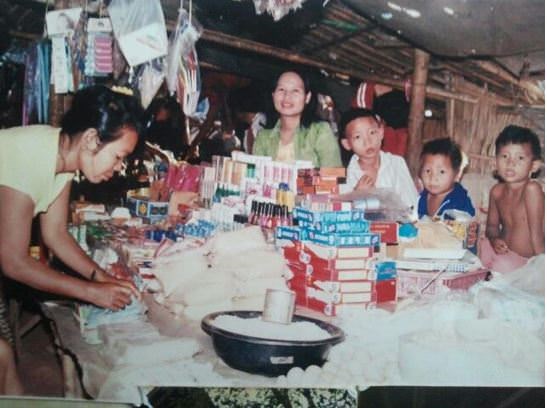

Our little shop

Trade went on. Although it was illegal, industrious people were trying to make money by starting small businesses. This shows to me that entrepreneurship is natural to us human beings, and that economics and trade are naturally emerging processes as people are always looking for ways to improve their lot and to fulfill their needs.

Thai merchants would come to the fences, away from the Thai soldiers who were patrolling, in order to sell food to the refugees inside. Such activities occurred during night-time. When Thai soldiers would find out that we were trading with outsiders, they would beat us and take away our belongings. We, refugees, were also not allowed to get outside of the camp or we would risk being shot dead by Thai soldiers.

During day-time, people inside the camp would expose their new belongings and small shops would emerge. My mother sold small products of convenience. Some of it was smuggled by Thai people into the camps that we, Cambodians, were selling to other Cambodians. Other things like oil and sugar were given to us as part of a food relief program that we used sparingly so that we could sell it further. With the money we earned, we could then buy other goods that we needed more.

Other ways through which we made money was by brewing alcohol made from rice and apples. Although alcohol was illegal, it did not stop my parents from brewing it. Whenever a Thai soldier would come to our house for inspection – I don’t think you can really hide the alcoholic odor that was surrounding our little house when we were brewing alcohol – my parents would bribe him with money so that he would leave us alone.

Continuing the story

These are some of my childhood memories of our lives in Khao I Dang. Maybe next time I can tell more about our life in the camp, share some of my older brothers’ memories, our cat that was lost, killed and eaten by someone or my first encounter with inspiring Superman and Spider-Man comic books. Maybe, I will also write about our continuing journey to the Netherlands and the psychological impact my experiences in Khao I Dang had on me.

I can tell about the nightmares that haunted me until my teenage years, how I always felt alienated from the people here and the inferiority complex towards Dutch people that I developed as a little child for feeling different. Feeling different made me feel insecure. Every time I met someone, and I think it lasted until my later teenage years, I would always ponder whether the person would kill me if he would be put in similar circumstances as those many killers from the Khmer Rouge period. In other words: as a child, I already wondered excessively about the “banality of evil”. These thoughts were of course extremely unhealthy, especially when you are as young as four or five years old.

The biggest lesson I have learned from my childhood is that both good and bad experiences are important in our lives. Happiness, in my opinion, is very much overrated and hardship is at least as valuable.

I have not written this so that people pity me. Pity, and in particular self-pity, is an extremely damaging emotion. It multiplies our suffering and reveals an extremely pathological egoism. When I look back at the hardships my family has overcome, I like to remind myself of Haruki Murakami’s saying that:

“Only assholes feel sorry for themselves.”

Serey is a Cambodia-based social platform and blockchain startup founded by Chhay Lin Lim. It established the Khmer Diaspora campaign to collect the personal stories of Cambodians young and old. Through blockchain technology, Serey can save these stories so they won’t be lost in the future, all while connecting members of the Khmer diaspora to their history and with each other.