Lander Perez has two rest days a week.

“It’s really very stressful work,” said Perez about his job counselling survivors of online sexual exploitation in boy’s shelter Kanlungan sa Er-Ma near the Filipino capital Manila. Though he finds his social work “priceless” and rewarding, the emotional toll can weigh heavy.

“Especially for us who are residential social workers, because we are directly living with the children. Every time you wake up, you see the faces of your children, and when you go to sleep, the last thing that you’ll see is their faces again.”

From his webcam on a recent video call, four pieces of A4 paper can be made out taped to his wall – three bible verses, and the last proclaiming, ‘Faith, Hope, Love’.

“Before this pandemic, usually I’d go outside, go to the mall, eat out, just have time to enjoy myself,” he told the Globe. “Now … I just stay in my room, I just have to rest and watch some random movies to release my stress.”

The online sexual exploitation of children (OSEC) has been proliferating in the Philippines for years, making it the global epicentre of the livestream sexual abuse trade according to Unicef. But making matters worse, pandemic conditions have meant this online exploitation has mushroomed in recent months.

On May 25, the Philippine Department of Justice Office of Cybercrime reported 279,166 OSEC cyber tips as the pandemic took hold between March and May – a 265% increase from the same period last year. In response, law enforcement and children’s rights groups have mobilised inter-agency initiatives against what NGO Save the Children have called the Philippines’ “secret pandemic”.

“Many of our partner shelters are almost full at this time, and rescues are happening almost every week,” said Adesty Dulawan. A psychologist and clinical supervisor at World Hope International (WHI), Dulawan supports child exploitation survivors and trains social workers, including Perez, on OSEC case management.

But the pandemic has presented problems with providing care, with live-in, locked-down social workers like Perez now among the only people serving a growing number of children in need of protection.

“Even us, we cannot go to the shelters anymore,” Dulawan said. “Some of our staff are doing interventions online for the children, but the most we can really do at the moment is supporting the social workers.”

A 2020 report from the International Justice Mission (IJM), an international NGO focusing on human rights and law enforcement, names the archipelago nation as the largest source of online child sexual abuse cases, with eight times more referrals than any other country.

The IJM report also wrote that IP addresses linked to the Philippines used for child sexual exploitation more than tripled between 2014 (23,333) and 2017 (81,723). Survivors were a median age of 11, the youngest under a year old. 41% of those conducting the exploitation were parents and 42% other family relations.

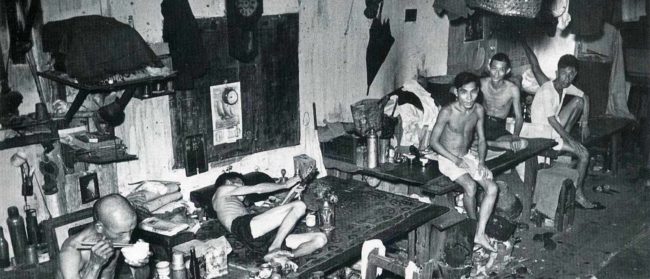

With widespread poverty, English language ability, and cheap internet access, the Philippines is a hotspot for perpetrators seeking cybersex transactions. These customers, overwhelmingly from Western countries, pay for the photos, videos, and livestreaming of the sexual abuse of minors. Usually, family members orchestrate the shows, which can draw $100 a broadcast. By comparison, the daily minimum wage in the country varies from $5.70 to $10.61 per day.

As a socially distanced world migrates online, so do economies of exploitation. Numerous agencies, such as Europol, Epcat Sweden, the UK’s National Crime Agency, have registered clear rises in online child abuse activities since Covid’s onslaught earlier this year.

“The trend that we’re seeing is that it’s only going to scale up,” said Dulawan.

Meanwhile, the Philippines’ stringent five-month lockdown and deepest economic contraction on record has left many jobless. The Philippines has recorded by far the most coronavirus cases in Southeast Asia with 190,000 as of writing, with almost 5,000 new cases on August 22 alone.

“Here in the Philippines, it’s quarantine – period,” said Lovely Galura, a residential social worker at Lost Coin Foundation’s girl’s shelter. Though restrictions vary across the country, for many households, only one member holding a ‘quarantine pass’ can leave to retrieve essential goods.

“A lot of work has closed,” she said. “And everyone is looking for financial support.”

National stress, inevitably, is running high. Amie Gosselin is external relations director at 10ThousandWindows, an NGO whose vocational training and rehabilitation services for survivors of violence and exploitation has had to go digital in recent months.

She said their crisis management hotline has been “ringing off the hook” since the start of the pandemic.

“People were extremely concerned that they couldn’t even feed their kids for the next 48 hours,” Gosselin said. “Interpersonal violence has spiked – people stuck in the same house, anxious and stressed … we’ve seen a huge spike in is suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.”

When offenders are being caught during lockdown, that will send the message to others that there’s a high risk of getting arrested when they engage in OSEC

Consequently, some households have turned to exploitation to make ends meet. This precarious combination – homebound cyber-abusers and a Filipino population stretched thin – means online child sexual exploitation has increased both in demand and supply.

“It’s difficult for [homebound children] to reach out for help,” explains Grace, a social worker in the Philippines who wished to remain anonymous.

What’s more, because of community quarantine, social workers are “blinded [from] what’s happening inside the home” she said, while schools, friends, neighbours and other family members cannot check on a child’s wellbeing as easily.

But while social workers are hindered, police raids soldier on. Since lockdown, IJM has supported 16 sting operations targeting online child exploitation.

Samson Inocencio, director of IJM Philippines, told the Globe via email operations had resulted “in the rescue of 61 victims and at-risk children and the arrest of 11 trafficking suspects”. Three prosecutions have also passed via virtual trial.

“When offenders are being caught during lockdown, that will send the message to others that there’s a high risk of getting arrested when they engage in OSEC,” he said.

Sheltering newly rescued survivors during a pandemic, however, presents novel problems.

“Initially, the shelters had been hesitant to accept children from outside because of the threat of Covid,” said Grace. But shelters soon adjusted. “Children are in need of protective custody because they have been at higher risk inside their homes.”

To prevent facility outbreak, the Philippine Department of Social Welfare and Development is quarantining children for two weeks after arrival. “They require Covid tests,” said psychologist Dulawan. “Remember, [the shelter] is a confined space, so they’ll all get Covid if even one gets Covid.”

Siblings of the same sex can also be isolated in the same ‘cottage,’ but siblings of different sexes stay in separate ‘cottages’ in the same compound.

“Securing our health, that’s number one, protecting our clients,” said Lost Coin Foundation’s Galura. “But it’s very challenging, this pandemic … the kids, they are bored in the house.”

Thankfully, Galura’s shelter has a garden where kids can play and plant vegetables. “We have activities, arts, game-based therapy, expressive arts therapy to help [them] express their emotions.”

Perez at Kanlungan sa Er-Ma said his team has to really “think outside the box” to engage the kids under lockdown.

“Usually we plan activities outdoors, but right now we are not allowed to go outside and it’s really affected the behaviour of our children,” he said.

Through art, children can share their stories at their own pace, and Perez has found expressive arts therapy a rich intervention that bodes well with the stay-at-home order.

But while the shelters are proving more vital than ever during the pandemic in protecting vulnerable children, those in the field believe there needs to be a transformation in how the sector operates.

“The Philippines has a very strong shelter-based culture,” Dulawan explained, adding that kids can be institutionalised for years, even until adulthood.

Though some children enjoy their life in the shelter, Dulawan thinks that in the long term, the system needs to change. “Family based care is still really the best form of care, not putting them into institutions.” Through WHI, she has been able to de-institutionalise about 146 children since 2018, with ongoing support.

Grace also thinks kids shouldn’t be sheltered long term. “What we need is to really strengthen the community-based mechanisms, to protect and prevent children from becoming victims of OSEC. We need to strengthen the families.”

She believes that, even though OSEC cases have been rising for years, the right response isn’t to build more shelters to house survivors. Nor is there a need for special OSEC shelters because survivors have “different dynamics”.

“You know, they are still children… [what] they need is a balance between warmth and structure.”

Now, more than ever, we need tech companies to innovate technologies to detect live streaming of abuse … These solutions could change the course of history for vulnerable children

In the meantime, major coalitions are moving to meet the cresting issue of spiking online child sexual abuse during the pandemic.

Organisations, the media and politicians are proliferating webinars, articles, statements, and calls for legal action, such as the Beat OSAEC 10-Day Digital Campaign initiated by the Child Rights Network in collaboration with several civil society groups. Perez and Kanlungan sa Er-Ma are also lobbying for an OSEC-specific law to improve judicial processes.

On August 10, spurred by Senator Imee Marcos, the Philippine House Committee on the Welfare of Children elected to begin an investigation into the OSEC spike. Marcos criticised telecommunications firms and internet service providers for failing in their legal duty to report cases of online child sexual exploitation, as well as detect and block the transmission of child pornography online

“Now, more than ever, we need tech companies to innovate technologies to detect live streaming of abuse,” called Inocencio. These solutions could “change the course of history for vulnerable children”, he added.

For Grace, the impetus must be on “strengthening the community-based mechanisms, strengthening the families as the frontline in the protection of children”.

“It is easier to build stronger children than to repair them,” she said. “The scars are – it’s like Covid – you cannot see who the infected are.”