Eyes seemed to look over Ros Saboeun’s shoulder as she flipped through an album of family photos. Her eyes glistened as each memory opened and closed. The sunlight reflecting off the wall of pictures behind Saboeun appeared to make the still stares glimmer as well.

“They were all so beautiful,” Saboeun said. “Especially, Sothea.”

Her home in Battambang is layered with legacy and serves as a living memory of the seven siblings Saboeun lost to the Khmer Rouge. A shelf of vinyl records from the Kingdom’s rock ’n’ roll past leans against a wall adorned from floor to ceiling with photos. The picture frames hang on aging posters advertising past performances by one of Saboeun’s siblings.

“There wasn’t a person in the country who didn’t know her name and most still do,” said Saboeun, pointing at a life-size bust of her younger sister, Ros Serey Sothea.

That name needs no introduction in Cambodia.

Sothea was among the most revered musicians in the Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s and was granted the honorary title of ‘golden voice.’ Her popularity among a generation of Cambodians persists today.

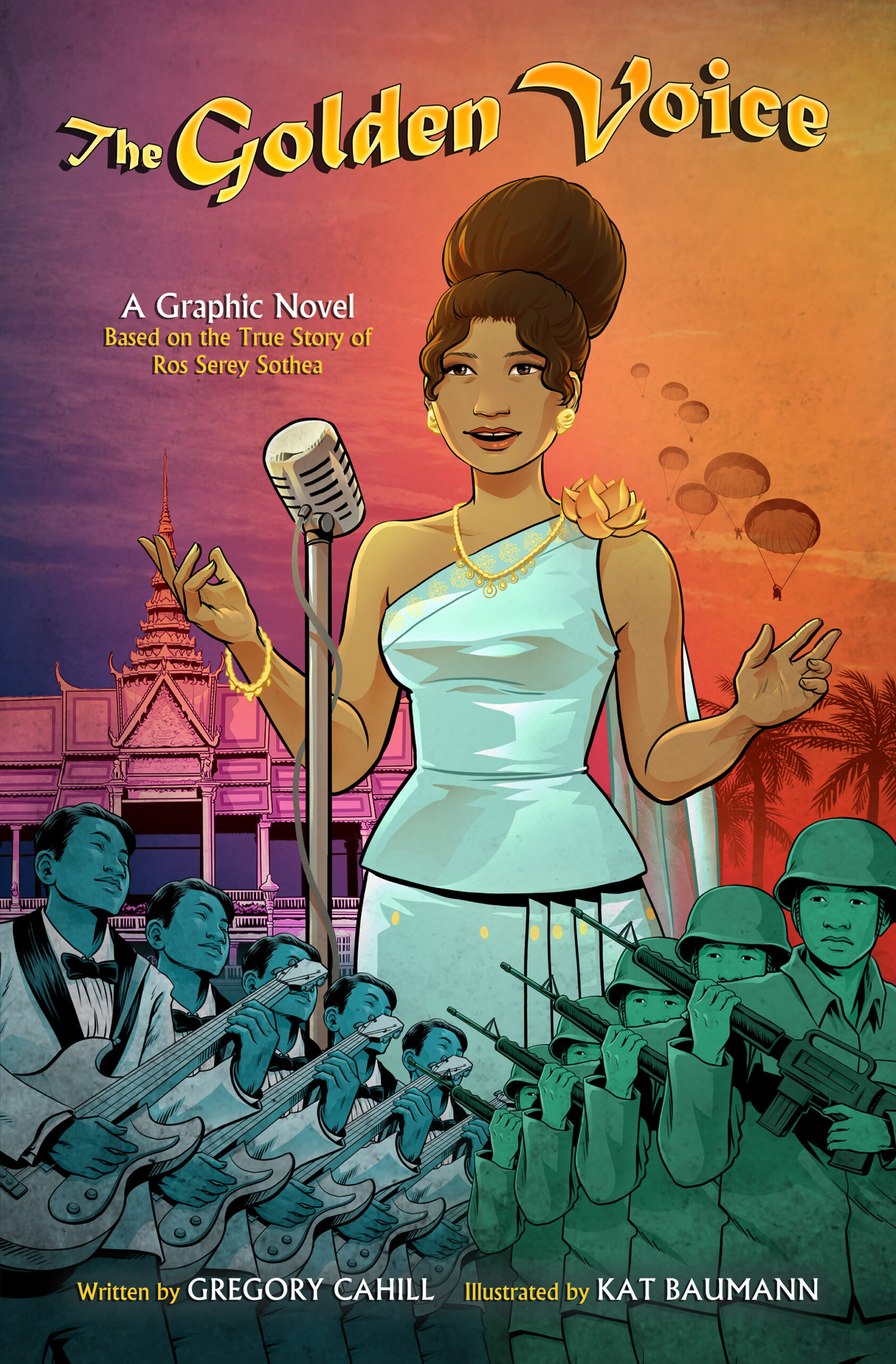

Plans are underway to retell the story of Sothea’s rise to fame as a graphic novel titled, ‘The Golden Voice.’

Closing the photo album, Saboeun rose from the floor for a more comfortable couch. Black and white photos of each of her siblings were directly at eye level from her seat.

“I worry, as more years pass, Cambodians will begin to forget our history and the people, like Sothea, who made it,” Saboeun said. “I’m happy her legacy is going to be told in a new way, like with this graphic novel. I hope I’ll be able to read it.”

The connection between Cambodia and Greg Cahill, who wrote the graphic novel planned for publication in 2022, began during his childhood in the US state of Massachusetts, when his parents worked as volunteers helping Cambodians resettle there.

Years later, Cahill listened to Sothea’s music for the first time when he was a recent film school graduate in the early 2000s. The soundtrack of a movie, ‘City of Ghosts,’ featured three of her hits: ‘Wait Ten Months,’ ‘Have You Seen My Love?’ and ‘I’m Sixteen.’

“I ended up listening to that soundtrack nonstop for at least a month and it got me into all these Cambodian singers from that era,” Cahill said on a video call from his home in California. “There was one singer, in particular, who really resonated with me. So I did what any young filmmaker would do and I decided to make a short film about that singer.”

Cahill’s film, ‘The Golden Voice,’ received several accolades but was not selected by producers for a full-length film. Surrounded by his wife’s collection of Manga graphic novels in 2019, Cahill realised the story needed to take on a new form: a graphic novel about the life of Sothea.

“At first, I thought a comic book would be a strange way to tell the story of a singer, but then I realised an entirely different approach is exactly what was needed,” Cahill said.

The novel includes a soundtrack, sourced from original vinyl records collected by the Cambodian Vintage Music Archive, to help readers experience Sothea’s voice as she sounded 50 years ago.

“Voices, like the one of Ros Serey Sothea, need to be preserved in their original form,” said Rotanak Oum, president of the music archive. “By doing that we preserve the legacy of the artist, which then protects the history of our Cambodian culture.”

As technology improved throughout the 1990s, music distributors had an easier time remastering old hits to make modern spin-offs. Oum saw these renditions as a misrepresentation of Cambodian classics and feared the original tracks would eventually be lost.

By ordering online from collections around the world and visiting Cambodian-Americans across the US, the music archive now has the original vinyl records of thousands of songs produced in the Kingdom during the 1960s and 1970s, including around 200 songs featuring Sothea.

“There is no double, she is the best, because Cambodians not only love her music, we loved her,” Oum said. “She grew up in a farming family, working the rice fields. Even when her life changed because of her fame, she stayed the same person. It was an inspirational story for Cambodians.”

While the graphic novel will naturally interest Cambodian audiences, Cahill said he hopes to connect with other American communities as well.

To help readers understand the intertwined histories of the US and Cambodia, Cahill wrote a significant subplot following the experiences of US military officers in Phnom Penh during the early 1970s.

“A big part of this for me is helping people learn about what happened to Cambodia and how the US was involved. Most Americans have no idea how deeply our government was involved in the civil war,” Cahill said. “This graphic novel is a good opportunity to help people think more about how our country’s foreign policy affects the lives of all kinds of people, like a singer.”

The novel includes introductory pages with comments from her sister, Saboeun, and directions for listening to the music archive’s soundtrack.

The opening pages are designed by Cindy Sous, whose earliest recollections of her own childhood in Massachusetts include the culture and music her parents brought to the US from Cambodia.

“I remember my mom singing along to Ros Serey Sothea during car rides and when we were just relaxing at home. For me, her music is therapeutic because it reminds me of those simple moments,” Sous said. “But I never understood the power behind the music and what it meant to my mom’s generation until I was much older.”

Connecting other first-generation Americans to the roots of their Cambodian culture is personal passion for Sous, who co-founded Khmer Identity, a social media platform highlighting aspects of the Kingdom’s culture and history.

“It was difficult to understand my Cambodian identity because the community was still healing from its traumatic experiences. We never talked about it and that left a lot of Cambodian kids in the dark,” Sous said. “That is why I want to use platforms, like ‘Golden Voice’ and Khmer Identity, to show there is so much more to the Cambodian community than our trauma.”

The pages designed by Sous will “embody the vintage look of that era” and take inspiration from aspects of the vinyl album covers to give it a “retro look and feel,” she said.

“If I had had this graphic novel growing up, I feel like I would have understood so much more about my family. I love the idea of representing Ros Serey Sothea’s story in this format because it expands the potential audience a bit more to younger kids,” Sous said. “I hope this novel brings back some power to the Cambodian community in America.”

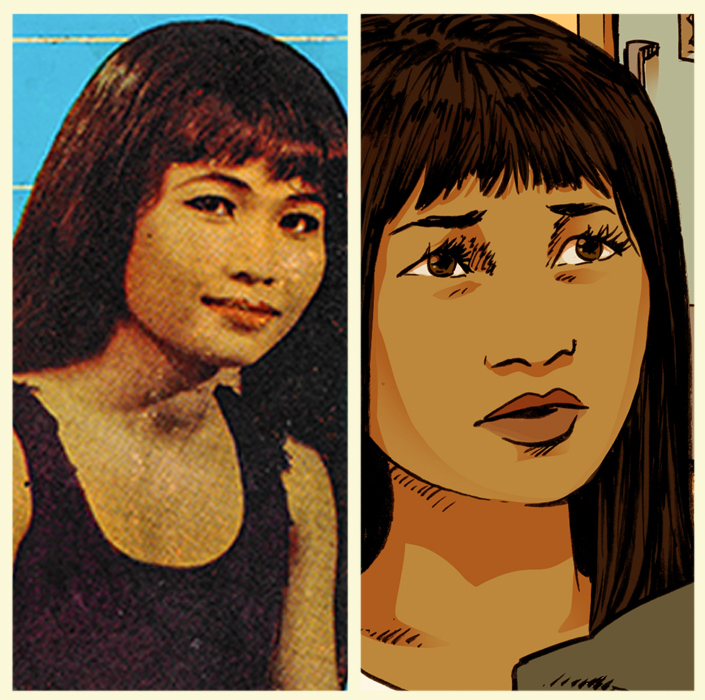

Artist Kat Baumann illustrated the final panels of the graphic novel on 7 November, the day after what would have been Sothea’s 74th birthday.

A remaining question is whether the novel will reach its intended audience. In the final month of 2021, Cahill was still searching for a publisher to distribute the novel in Cambodia.

“I am new to the book publishing world and I’m not too savvy about how book publishing works in Cambodia, but it is a priority for us to get this novel translated into Khmer and distributed in Cambodia,” Cahill said.

Uth Roeun, one of Cambodia’s most famous comic artists, said finding a publisher to translate and distribute a graphic novel in the Kingdom would be a difficult task.

In the 1960s, Roeun rose to fame by retelling classic Cambodian literature in graphic novel form. He said the popularity of comics, and printed books as a whole, has dropped significantly since then.

“In the past, graphic novels supported the spread of literature because it helped people from different educational backgrounds understand the meaning and lessons of our history,” Roeun said. “But with the internet, nobody needs that now. There are lots of resources and tools available people can use to educate themselves for free.”

Roeun still draws regularly, posting his latest work on social media. He has built a loyal audience of more than 3,000 Facebook followers. Despite the level of engagement each post receives, Roeun said none of his fans would buy a printed book of his comics.

“There is no demand for books in Cambodia. People only care about if they have food on the table and money in their pockets. They don’t have time to read,” Roeun said. “Publishers are right to be hesitant in printing anything, especially graphic novels, because it is risky.”

If printing ‘The Golden Voice’ in Cambodia proves impossible, Cahill said he would investigate digitally publishing a Khmer version of the novel.

“This story comes from Cambodia and it would just be odd if the novel wasn’t available in the Khmer language,” Cahill said. “We’ve received a lot of enthusiasm on social media from people in Cambodia, so we are going to do everything we can to get a version of it there.”

Following the graphic novel’s publication in the US, Cahill hopes to visit Cambodia and host a book tour to celebrate Sothea and her surviving family.

“It is a dream of mine to hand Saboeun a copy of the graphic novel in person,” Cahill said. “To thank her for all she has done for her sister, and for all her sister has done for Cambodia.”

Even though it has been decades since their deaths, Saboeun said she has an eternal responsibility as the eldest sister to protect her family’s legacy.

Standing up from the couch, Saboeun walked past her sibling’s photos and stopped at the record shelf. She pointed between the clutter at a little space reserved for the graphic novel that may encapsulate her sister’s story for generations to come.

“That is where I will put my copy,” Saboeun said.

Additional reporting by Borin Sopheavuthtey.