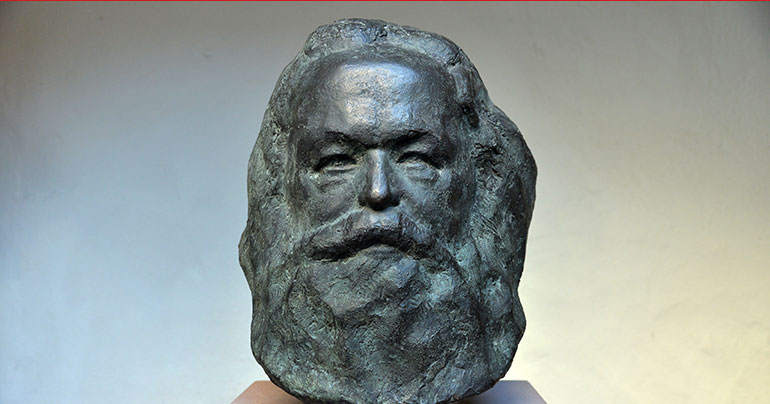

Contradictions come easily in Vietnam, be it the Communist party flags bearing the golden hammer-and-sickle flapping in front of the golden arches of McDonalds, or Vietnam’s close relationship today with the United States, its former aggressor. Another is the fact that, as one of the four last remaining nations that consider themselves Marxist-Leninist, there is scant mention of Karl Marx in Vietnam, even as this month marks the bicentennial of the birth of the grandfather of the communist cause.

His image, along with Vladimir Lenin’s, appears only in miniature on the party’s propaganda banners, overshadowed by the figure of Ho Chi Minh, the national hero. Even the hawkers of junk tourist artefacts offer up little of Marx – just commemorative tableware and historic postage stamps. One can come away with a T-shirt emblazoned with the hirsute philosopher, but only after some hunting.

Outside the Reunification Palace in Ho Chi Minh City, Giang, a technology student who asked for his second name to be withheld, says he had to study Marx at high school but didn’t find the topic interesting or relevant, an opinion shared by many other young people Southeast Asia Globe spoke with.

“He’s not important any more in Vietnam,” Giang says, adding that the younger generation has a greater affinity with the likes of Mark Zuckerberg and the late Steve Jobs, the founders of Facebook and Apple, respectively. About 40% of Vietnam’s population is below the age of 24.

Classes on Marxism-Leninism and ‘Ho Chi Minh Thought’, as the national philosophy is known, are compulsory in high school. But, in 2013, the party had to make these ideological courses free at state-run universities because of a lack of interest.

Over a few Saigon beers – a brand controlled by a state-owned brewery until a Thai firm paid $4.8 billion in December for a majority share, part of Vietnam’s ongoing jettisoning of state-owned firms – one middle-aged local cites Marx as the reason his country was poor for decades, and the teachings of Adam Smith, the philosopher considered the father of modern capitalism, the reason why Vietnam is now wealthy.

It is safe to say, though, that a few Vietnamese will be thinking of Marx on 5 May, the philosopher’s birthday. It certainly won’t be a big affair, according to Christopher Goscha, a historian of Southeast Asia at the Université du Québec à Montréal. “There will be the required commemorations but they will be low-key, limited in number and occur mainly within the domain of the party apparatus,” he says.

Wealth inequality is rapidly widening: Vietnam’s richest person earns more in a day than the poorest earns in ten years

The party still reads from the Marxist canon, but only intermittently. Since the 1980s, party grandees have ceased their trumpeting of the “class struggle” and “proletarian internationalism”. Instead, their new language is of economic prosperity for all, a more generic promise. This is chiefly the result of the Doi Moi reforms, introduced in 1986, that replaced a centrally planned economy with the free market. But party jargon still splits the difference: Vietnam has a “socialist-orientated market economy”, contend the apparatchiks, or party members.

Granted, they have had some successes. Poverty rates fell from almost 60% in the 1990s to about 20% today, according to the World Bank. But wealth inequality is rapidly widening: Vietnam’s richest person earns more in a day than the poorest earns in ten years, according to a recent Oxfam report.

“The rich-poor divide only shows signs of getting worse,” admitted Nguyen Phu Trong, the current party general secretary and the nation’s most powerful politician, in 2013. Corruption is also on the rise. A recent report by Transparency International ranked Vietnam the second-worst country in Asia-Pacific, after India, for petty graft; 65% of respondents said they had to pay bribes to access public services.

Political analysts say the party’s core message – “We take care of everything, so you don’t have to” – is looking increasingly specious, as is the party’s legitimacy, considering it hasn’t held free elections in decades. This journalist was told years ago by a renowned dissident that many Vietnamese consider their current situation to be the worst of both worlds: unfettered capitalism and unwavering authoritarianism.

Amid this, Hanoi is busy imprisoning critics at a rate not witnessed in decades. The latest estimate suggests there are more than 100 political prisoners, though that number is increasing by the week. Many won’t be released from jail for decades, but this hasn’t perturbed the pro-democracy movement. Activists say it’s sturdier than ever, combative as the government becomes more confrontational. Nguyen Chi Tuyen, a prominent human rights defender who goes by the online name ‘Anh Chi’, says “the communists use [Marx’s] philosophy as a tool to control our minds”. But, he adds, anti-party protestors often employ Marxist language to criticise the regime.

Labour-rights activists who requested anonymity say they sometimes evoke Marx as a means to promote their cause, arguing the party has forgotten about the working class. Environmental activists maintain that communist leaders now leech onto ruinous capitalists, such as the owners of the Formosa steel plant that, in 2016, spilled tonnes of toxic waste into the coastal waters around central Vietnam. Communities have been left devastated; many won’t recover. Hanoi, at first, came to the defence of the factory’s Taiwanese owners. Only after unprecedented protests did it change tack. “Marx would have been on our side, not theirs,” says one activist who asked not to be named.

The historian William J. Duiker, in his biography Ho Chi Minh: A Life, wrote that since Uncle Ho’s death in 1969, party grandees have continued to debate his legacy. His goal, most say, was to end capitalist exploitation and create a revolutionary world “characterised by the utopian vision of Karl Marx”. But, as Duiker notes, some dissenting voices say he wanted to “soften the iron law of Marxist class struggle by melding it with Confucian ethics and the French revolutionary trinity of liberty, equality and fraternity”.

If so, the party is revising this. While the “socialist-orientated market economy” might sound like a euphemism, it is actually much closer to Marx’s understanding of the way societies development (the “materialist conception of history”, in Marxist jargon) than Ho Chi Minh’s belief that Vietnam, in the mid- 20th century, could hoist socialism upon what was basically a feudal country. Marx argued a capitalist stage was necessary in between.

Indeed, what proponents of the socialist-orientated market economy maintain is that Vietnam must now develop the productive forces of a capitalist society, including an industrial economy, a working-class base and national wealth. Only then, they say, can Vietnam achieve socialism.

“The market economy of its own cannot destroy socialism. But to build socialism with success, it is necessary to develop a market economy in an adequate and correct way,” said current Party General Secretary Trong on a visit to Cuba, another socialist nation, in March.

Party theoreticians take these things seriously. After all, Trong was president of the central committee’s Theoretical Council during much of the 2000s. At a central committee session last year, he announced that 2030 will be the deadline for when the aforementioned socialist-orientated market economy must be completed.

Exactly what it is supposed to resemble remains questionable – and it isn’t without internal criticism. Bui Quang Vinh, a former minister of planning and investment, reportedly said in 2014 that “we keep studying that model, searching for it in vain. There is no such model to be found.” What most observers reckon is that the whole enterprise is mere theoretical contortionism, an attempt to adapt to the “new environment without having to question [its] monopolistic power”, says Benoit de Treglode, a Vietnam expert and director of research at the Institute for Strategic Research in Paris.

If true, Marx matters for another reason. Hoang Minh Chinh was a Moscow-educated communist politician until he turned party critic in the 1960s. He would spend the rest of his life, until his death in 2008, in and out of jail for insisting the party had to reform and democratise. The historian Christopher Goscha, in his The Penguin History of Modern Vietnam, writes that Chinh wanted to remind Vietnam’s communist leaders that they were on the wrong side of history, first in the late 1950s as the Soviet Union underwent its “de- Stalinisation” programme and then in the 1990s as the Soviet bloc collapsed. “[Chinh] praised the 19th century German socialists who, despite Marx’s rebuke of their ‘revisionist’ moderation, had pushed through a groundbreaking political programme at Gotha in 1875,” Goscha writes, referring to a 19th century party congress in the German town of Gotha that laid out how to commingle Marxism and electoral politics – what today might be called social democracy. But Marx, in a famous polemic, rejected it as too moderate and “revisionist”.

“Chinh symbolises a strand of Vietnamese democratic socialism with republican influences, and I believe that he was not alone within the party to hold these ideas,” Goscha told Southeast Asia Globe. What political observers are asking today is whether the party still has such believers in social democracy and whether the party can reform, even democratise, from within. As such, the old Marxist debates alive in Europe in the 19th century are now spoken afresh in Asia in the 21st century.

Most commentators, however, believe that change is impossible under the current leadership of Trong, a conservative who is willing to maintain the party’s rule by whatever means, either through socialism or capitalism. That said, the semantics of a socialist-orientated market economy must be of some comfort for party loyalists who have spent their entire lives studying Marxism only to discover many of Vietnam’s woes have been solved through capitalism.

But, then, those who try mastering a new language, as Marx once wrote, begin by translating it back into a language they already know.