When asked about the upcoming results of her latest criminal trial, Maria Ressa almost brushes off questions, instead turning to the bigger-picture questions on her mind.

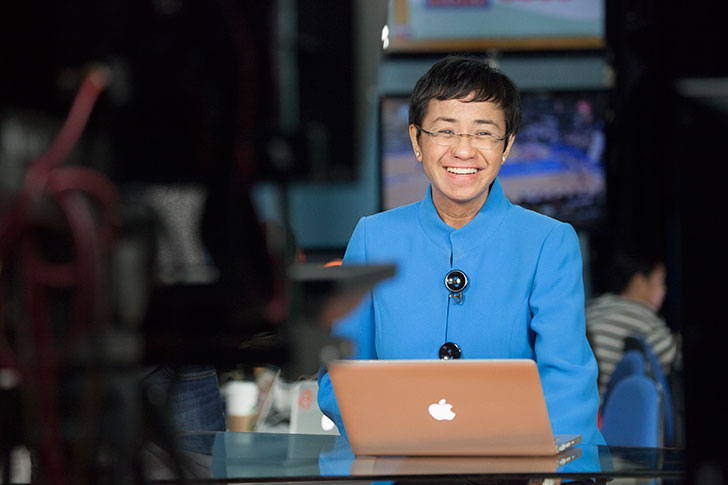

“I never wanted to fight the government,” said Ressa, founder and CEO of Rappler, a Filipino media outlet based in Metro Manila. But she’s been in a yearslong legal battle with the government nonetheless that has recently culminated in a raft of criminal charges – including a count of “cyber libel” that human rights groups have blasted as “absurd” and for which Ressa is now awaiting court verdict.

Ressa was charged with eight criminal violations in 2019 and posted bail all eight times. Though her court date for the cyberlibel case has been delayed to April 24 by the effects of the global Covid-19 pandemic, she could face a potential 12-year-sentence in prison if convicted of that alone. When recounting the charges levelled against her, she says the Filipino government is attempting a legal strategy of “death by a thousand cuts”.

The cyber libel case stems from an article published by Rappler in May 2012 after a reporter investigated Renato Corona, former chief justice of the Philippines Supreme Court, who was facing an impeachment trial at the time. Sources told Rappler that Corona had been using a vehicle owned by a businessman with alleged criminal ties. The businessman was named in the resulting article and, five years later in 2017, filed a complaint with the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) cybercrime division to dispute how he was represented.

The case was initially dismissed because of a one-year statute of limitations on libel. But just a few weeks later, the NBI recommended Rappler be prosecuted for cyber libel, a distinct charge which does not have a statute of limitations. Ressa was arrested and later posted bail.

Rappler released a statement saying the case sets a “dangerous precedent that puts anyone – not just the media – who publishes anything online perennially in danger of being charged with libel.”

“It can be an effective tool of harassment and intimidation to silence critical reporting on the part of the media”, the statement read. “No one is safe.”

The flexibility of the charge and the potential for steep sentencing drew red flags from the international legal community. Ressa is now represented by 40 defence lawyers, including the high-profile human rights lawyer Amal Clooney.

Southeast Asia Globe spoke with Ressa on March 16, a few hours after her trial date was rescheduled for late April. She was initially supposed to hear the verdict on April 3, but now, due to the pandemic spread of the novel coronavirus, Filipino courts are open for essential services only until April 15, a date that may be pushed even further.

Other charges filed against Ressa in 2019 include alleged crimes in how Rappler itself is run, including charges of tax evasion and violation of the anti-dummy law, a statute to prohibit foreign ownership in certain economic sectors.

While it has never been easy being an independent journalist in the Philippines, she began to face more intense vitriol in late 2016, when she published her findings about the use of misinformation and propaganda during President Rodrigo Duterte’s 2016 election campaign.

If the government won’t tell us how they’re dealing with it, we will ask the questions, we will try to get to what the solutions can be

Ressa has long been a vocal critic of Duterte and has been committed to investigating his self-proclaimed “war on drugs,” among other topics related to his administration’s often heavy-handed approach to civil rights.

Press freedom advocacy group Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has named the Philippines as among the top-four worst offenders for spreading state-sponsored disinformation online. In such a contentious news environment, Ressa says she’s had to adjust to the harsher realities of publishing independent news here.

“I’ve had my rights curtailed because I’m a journalist”, she said. “And the irony for me of course is that now, more than ever, the government needs to work with journalists. And you know, I’m not alone.”

Ressa can sound blasé about her own problems. When asked about them, she immediately switches the subject to the global pandemic and the Filipino government’s response.

The countrywide shutdown was abrupt and sweeping in nature: A ban on public transport, for example, was instituted with just a few hours’ notice, leaving commuters scrambling to enter the city. The Philippines was also the first country to shut its financial markets, a move met with controversy.

On April 1, Duterte warned that violators of home quarantine orders would be shown no mercy, instructing the police and military to “shoot them dead.”

The strongman leader was unsparing in his rhetoric.

“Is that understood? Dead,” he said in a public address. “Instead of causing trouble, I will bury you.”

Rappler covered this speech and is dedicating significant manpower and resources to reporting on as many angles of the pandemic’s impact on the Philippines as possible.

“The world is fundamentally, drastically changed,” Ressa explained. “And we are working around the clock to cover this.”

Before founding Rappler, Ressa spent two decades working as CNN’s lead investigative reporter in Asia. She went on to open CNN’s Manila bureau in 1987 and its Jakarta bureau in 1995. Later, for six years, she headed up the largest news group in the Philippines, ABS-CBN.

Ressa believes the size and breadth of large networks like CNN and ABS-CBN are the very things that prevent them from being agile in their innovation and adaptation. Her proposal: A media outlet that could flex and bend much more quickly to meet the needs of the community.

And so Rappler was born, first on Facebook in 2012, and then as a full-fledged news website.

Part of the philosophy driving the new, independent media outlet for the Philippines was connection with the community. Rappler is equal parts editorial team and civic engagement tool, a blend of strategies that work separately but come together to push Ressa’s goal of aiding and informing the Philippines.

“The elevator pitch for Rappler is one sentence: We build communities of action,” she said. “And that already shows you how different we were from traditional media.”

That model may prove crucial, especially as accurate information is becoming difficult to obtain and parse given the firehose of Covid-19 updates.

Rappler’s transition from a Facebook niche to a media outlet with a monthly audience of 12 million has not been easy. The publication’s leaders have increased security at its offices multiple times this year.

As of March 15, all journalists had to register for accreditation from the government in order to be exempted from community quarantine. Ressa was initially fearful that Rappler staffers would not receive accreditation as some form of retaliation, preventing them from reporting on Covid-19 in an in-depth way.

While they did receive accreditation after a tense waiting period, Rappler joined other media organisations, press freedom advocates and academics in signing an open letter decrying the government decision to require it.

Ressa believes the role of the media is especially important during the crisis times of Covid-19.

“We’re not getting any real facts or any methodology, or a framework of thinking about the coronavirus from the government right now”, she said. “If the government won’t tell us how they’re dealing with it, we will ask the questions, we will try to get to what the solutions can be.”

Until something else happens, Ressa continued, until journalists are shut down by criminal cases like the many on her docket, are persecuted further or even physically harmed, all they can do is try to set the record straight.

“The propaganda war is still ongoing,” she said.