The drive from Timor-Leste’s capital city Dili to the small village of Balibo took nearly three hours, with the Mitsubishi Jeep speeding along the scenic, western coastline. At the time, none of the three passengers in the vehicle knew that only one would make it back to Dili alive.

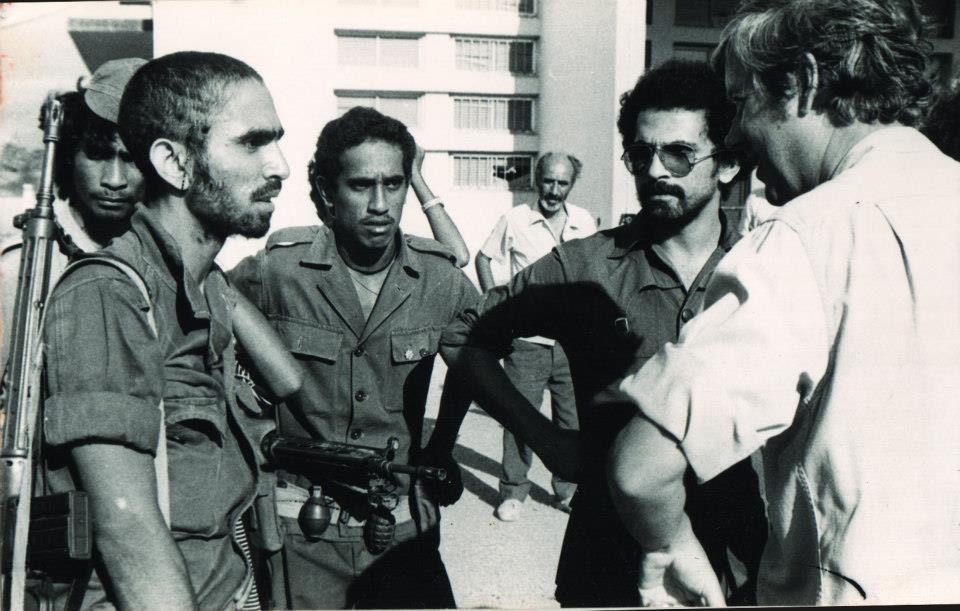

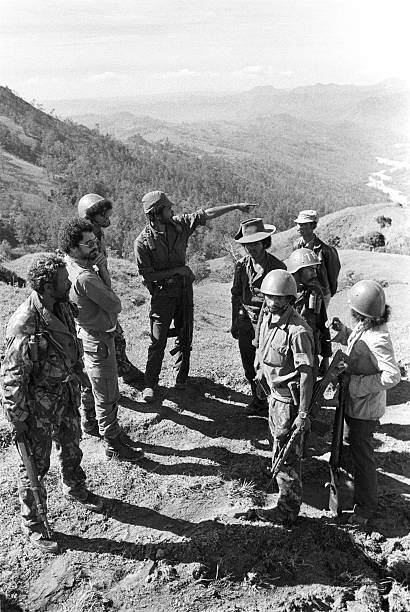

It was October 1975, and José Ramos-Horta had been tasked with accompanying two foreign journalists from the capital to a military camp in the central village of Balibo. They were joining three journalists who had arrived a few days earlier. Together they made up what would fatefully become known as the Balibo Five.

Only days later, the journalists were murdered by Indonesian soldiers in an event that shocked the world. It also precipitated the Indonesian invasion to come that December, starting Jakarta’s quarter century-long occupation of its small neighbour.

“We never thought they [Indonesians] would dare to capture and in cold blood murder journalists. That was totally unexpected,” said Ramos-Horta. Then just 24-years-old, he would go on to win a Nobel Peace Prize and serve as both prime minister and president of Timor-Leste.

“But what they [Balibo Five] underestimated – that I underestimated – was the Indonesian determination to eliminate any witness to their [invasion].”

At the time of the Balibo trip, Ramos-Horta was serving as the Minister of External Relations and Information within Fretilin, the largest group opposing Indonesia’s advancement into Timor-Leste. Pushed into exile following Jakarta’s invasion, he travelled the world lobbying for support amidst mounting geopolitical tensions that left Timor-Leste isolated and riddled with conflict under the occupation.

Now, 25 years since his 1996 Nobel Peace Prize award, Ramos-Horta spoke to the Globe via video from his home in Dili, spelling out the significance of this fateful press trip within the context of an imminent Indonesian invasion, the wider Cold War and Timor-Leste’s struggle for independence.

“The Indonesian propaganda machinery kept churning out fake stories saying that there was a civil war still going on, creating this whole scenario of an impending catastrophe and they would come and liberate us. But, at the time, there were no more civil war, the civil war only lasted two weeks,” Ramos-Horta said.

“So my responsibility was to challenge this propaganda, and nothing better than with independent journalists. I connected with media abroad – New Zealand, Australia, US, Japan – trying to bring journalists to Timor-Leste to cover the situation here.”

In late 1975, shortly after the Balibo trip, tensions between Indonesia and Timor-Leste had escalated and Fretilin sought out international support to counter the Indonesian forces. Ramos-Horta was selected as the group’s de facto spokesperson and arrangements were made for him to travel abroad.

“I can manage a gun, but that’s not exactly my purpose. My function was in the international field. So I went to New York, which was an experience. I had this secret novel mission, this impossible mission to lobby the UN.”

Arriving in New York, the cosmopolitan city was nothing like home.

“I wouldn’t say it was a traumatic experience because I don’t get traumatised that easily, but it was most unpleasant. Arriving in New York in December, that particular year it was very cold and there was snow everywhere, and I’d never seen snow in my life,” recounted Ramos-Horta.

Despite the novelty of the city and the cold weather, Ramos-Horta jumped into his role as a diplomat, securing meetings with members of the UN Security Council and lobbying for support among representatives from post-colonial countries across Africa and Central America.

While the former president recounts that many of these conversations were fruitful, they ultimately yielded little in terms of tangible results. Cold War-era superpower allegiances reigned over all decision-making in the international arena, and the small island nation of Timor-Leste was often collateral amidst regional tensions and fears of communist proliferation.

Though Ramos-Horta maintains that Fretilin was never a communist party, paranoia surrounding leftist movements in Southeast Asia, particularly in the wake of the US war in Vietnam, contributed to international support for anti-communist dictator Suharto.

“Indonesia’s invasion of Timor-Leste was likely motivated by the post-Vietnam syndrome. The embarrassing defeat in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, and the American tragedy that destroyed Indochina and killed so many millions of people in the name of the fight against Soviet and Chinese communism,” said Ramos-Horta.

“To think that Timor-Leste, which at the time had only about 600,000 people, would be another communist enclave, that is far-fetched by any stretch of imagination. We were led by Catholic leaders, nothing to do with communism.”

Whispers of Marxist ideologues permeating Fretilin’s ranks had been prevalent since its founding in 1974 as a pro-independence group, securing liberation from Portuguese rule a year later. By the time the Balibo Five arrived in Timor-Leste in late 1975, this reputation had reached international ears and was driving support for Suharto’s Indonesia, the largest anti-communist force in Southeast Asia.

With rumours of an imminent invasion swirling, Ramos-Horta remembers warning the men that they should return to Dili a few days after arriving. They refused, driven by a mix of adrenaline and a conviction to tell the story of the Timorese people.

“I told all of them, I’m returning [to Dili], I would advise all of you to return with me but they said, ‘no, we came here to film some action’,” said Ramos-Horta.

“I remember [one of the journalists] Greg Shekleton making this comment to his colleagues, ‘We have to report this to the public, to the outside world. We have to help these people, we can see that they just want freedom for their country.’”

Ramos-Horta returned to Dili alone. Three days later he would be notified of their murder.

Unsure at first if the rumours were true and hopeful that the men had only been taken hostage, Ramos-Horta issued a statement on behalf of Fretilin urging their immediate release, offering imprisoned Indonesian soldiers in exchange. But two days later, their deaths were confirmed.

After the murders were uncovered, a multilateral cover-up operation was initiated by Australia, where all five journalists had been working, fearful that the incident would jeopardise Indonesian plans in Timor-Leste. The cover-up pushed the narrative that the journalists were killed in the crossfire as Indonesian forces faced off against Falintil, the armed wing of Fretilin.

Even to this day, Ramos-Horta becomes angered as he speaks about the incident and its aftermath, alleging that deception on the part of Australia and the West emboldened Indonesian forces as they prepared to invade.

“They were not killed in crossfire. They were captured alive and were brutally murdered with knives. They were so mutilated that to hide the physical evidence of how they were killed, they were burned beyond recognition and became ashes,” said the former president.

“If Australia had stepped in and loudly protested the killing of the [Balibo] Five, demanding the truth, and had Australia shown courage in raising the issue at the UN, probably the [Indonesian] invasion would not have happened. 200,000 people would not have died. My own sister and two brothers, who died during the occupation, would be alive today.”

This was my first introduction to international hypocrisy – the same Western countries in the security council had voted yes on the resolution condemning the invasion, went on selling weapons to Indonesia

The full truth of what transpired in Balibo in October 1975 only came to light at the turn of the century, when journalist Jill Jolliffe published a report into Australia’s role prior to and following the invasion.

The book was a turning point in the investigation into the murders, confirming that Australia knew that Indonesian forces had already begun arriving in Timor-Leste prior to the occupation and the cover-up following the attack.

But Australia was not alone in their quiet support for Indonesia. In a series of communications and an in-person meeting in Jakarta in 1975, Indonesian president Suharto spoke with US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and President Gerald Ford. Both men confirmed that if Indonesia was to go ahead with their intervention in Timor-Leste, the US would not stand in their way.

Rising communist affiliations within Fretilin in the late 1970s only cemented Western support for the Indonesian occupation. In 1978, Nicolau Lobato, a prominent leader within Fretilin, was murdered in combat and Xavier Amaral was ousted as president, leaving the group’s leadership open. The subsequent reshuffling of the party’s top echelons saw an influx of Marxist factions that unofficially rebranded the party as communist.

Back in New York and Washington, these changes made Ramos-Horta’s job as a lobbyist all the more difficult, particularly in rallying support among American and European countries. He recounts that many Western countries would agree to peace deals on paper, but failed to keep their word behind the scenes.

“This was my first introduction to international hypocrisy – the same Western countries that in the [UN] security council had voted yes on the resolution condemning the invasion, they went on selling weapons to Indonesia,” explained Ramos-Horta.

“They all agreed that Indonesia was the most important anti-communist front in Southeast Asia.”

While he continued to lobby for Western support, Ramos-Horta also saw merit in playing on Cold War divisions to win favour with communist countries. He sought out a meeting with representatives from the Soviet Union, hoping to capitalise on animosity towards the US.

“I had a funny experience with the Soviet ambassador Yacob Malik. One afternoon, I sat down with him, but he was sleeping most of the time. Our meeting lasted for twenty minutes, then he woke up and said ‘we will support you’, meaning he would vote in the security council,” said Ramos-Horta, laughing as he retold the story.

“This was easy for the Soviets because anything that would upset the Americans they would do. Not that they were sympathetic to us – Timor-Leste had no strategic interest value to the Soviet Union.”

By 1994, after two decades of lobbying world leaders to little avail, the future president began looking for new ways to raise the plight of the Timorese. In such an effort, he turned his attention towards the Nobel Committee and began lobbying it to award the Peace Prize to Bishop Carlos Belo, a leader within the Timorese peace process.

After two years of failed campaigns, in 1996, he finally received word of their selection. Bishop Belo had been selected for his in-country work within the church, working to advance the peace process despite threats to his life. Ramos-Horta, a surprise inclusion for the award, was selected for similar efforts abroad.

“A friend of mine phoned me and asked me, ‘what do you think about this year?’ and I said, ‘I don’t care, they can give it to anyone they want, I don’t want to hear about the Nobel Peace Prize again,’ said Ramos-Horta. “Well a few days later Bishop Belo and I got the news, and, for me, totally by surprise.”

While other factors were at play – namely the 1997 economic crisis that swept through Asia, contributing to Suharto’s resignation in Indonesia – Ramos-Horta credits the award with providing a major step towards securing Timor-Leste’s 1999 independence referendum.

“It was enormously important for the visibility of the struggle, for my visibility as a spokesperson for the Timorese. It enabled me to have doors opened wide in Washington and elsewhere, in Europe.”

The newly opened doors precipitated greater international pressure on Indonesia to hold a referendum, in which the Timorese were given the opportunity to vote for either greater autonomy under the Indonesians or a fully independent state. The vote came back 78.5% against special autonomy within Indonesia and in favour of complete independence.

For Ramos-Horta, who had been barred from his homeland since the invasion in 1975, the referendum sparked hope that he might be able to return – something he finally did in December 1999.

“An estimated 10,000 people were at the airport welcoming me. I was totally surprised and overwhelmed. I had heard from different people how popular I was in the country but if only one hundred people had turned up at the airport I would have been surprised,” said Ramos-Horta.

“I didn’t feel right that I was in a car and they were walking, so I got out of the car and walked with them. We walked all the way from the airport to the government building, it took us two hours.”