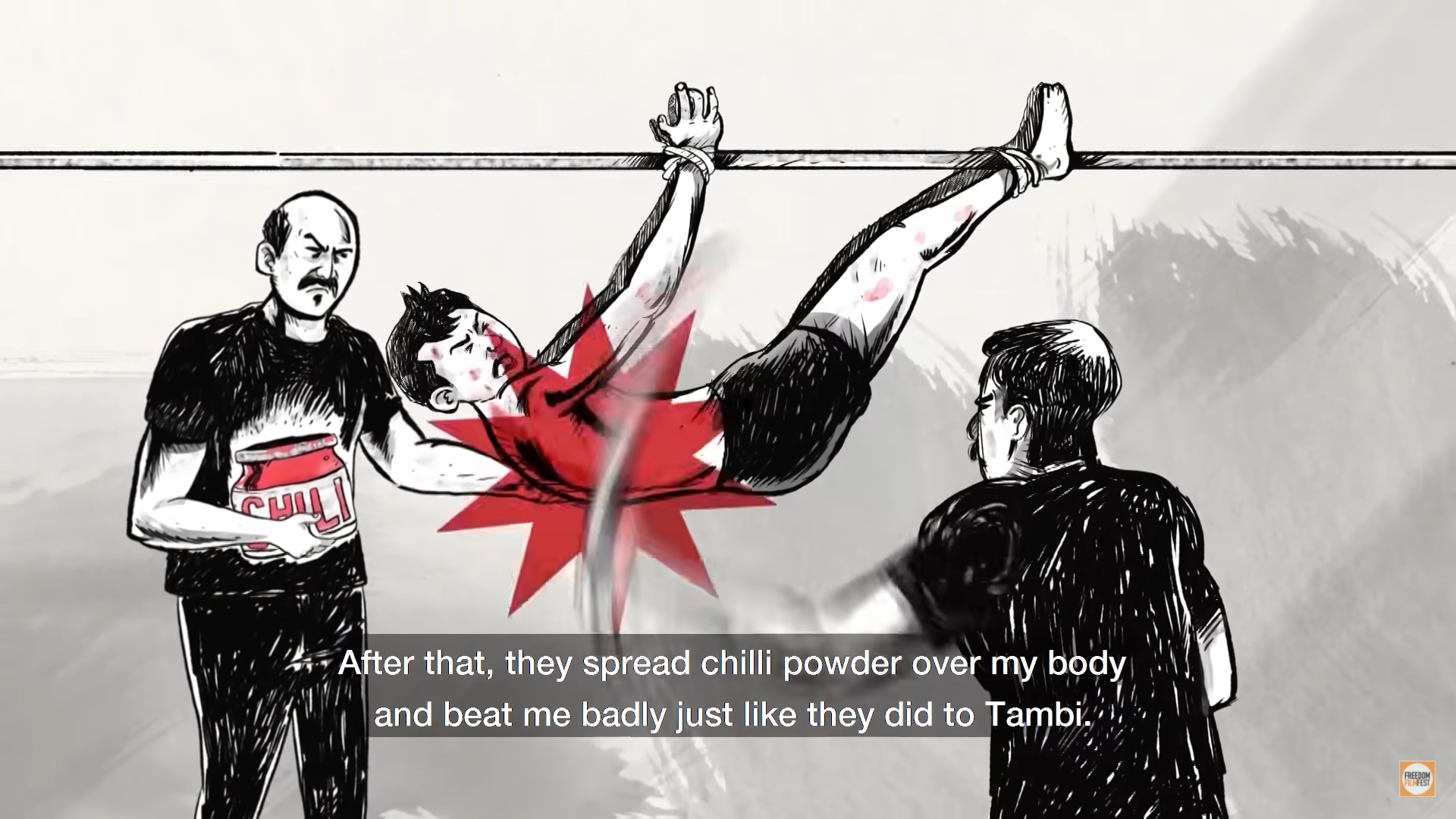

Like a rotisserie chicken, teenager San is bound and hung on a stick by his wrists and ankles.

The everyday tools of torture are seen lined up in a row – buckets of chili powder and paint thinner, combined into a paste for their potency. A police officer donning boxing gloves towers over him, beating him senseless while working in a coat of the red mixture onto his bruised skin.

These were the scenes in a recently released short animated film, Chili Powder and Thinner, in which police officers stand accused of torturing three teenage boys – San, Tambi, and Kula – in a custody centre on February 6, 2018.

Amin Landak, the film’s cartoonist, employed this striking imagery to highlight an important issue that has come to the fore once more in Malaysia – deaths in police custody.

“The way I’ve chosen to illustrate this is completely out of character. I used rough and almost sketch-like strokes to show the brutality behind it,” he told the Globe.

The four-minute film is based on testimony by 16-year-old San, recounted to human rights group Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), and released by the Freedom Film Network in mid June. Following a spate of reported deaths in police custody this year, it has tapped into a wider conversation about police accountability and brutality in Malaysia, usually hidden behind bars. Authorities, seemingly rattled by the film’s impact, have opened several police investigations into the team behind it since its release.

The film’s producers released Chili Powder and Thinner to push forward the long-running public discourse on establishing an Independent Police Complaints of Misconduct Commission (IPCMC) bill, which has come to the forefront once again after an increase in reported custodial deaths across Malaysia in 2021. Already this year, there have been 12 reported deaths of detainees, people held in police custody who have not been convicted of a crime, compared to nine in all of 2020.

Mohammad Alshatri, programme officer at SUARAM, who also directed and wrote the script for Chili Powder and Thinner, said that this number is heavily underreported.

“The majority of the cases documented were because of health issues, neglect, not being given proper care, and mistreatment,” said Mohammad. “Our records are probably 25% of the parliamentary data of all deaths in custody in Malaysia.”

After his gaping wounds were left untreated, Kula joined this list of victims. Before becoming another custodial death statistic, Kula was on his way to pick up a friend with San and Tambi, before being pulled over for having mismatched car plate numbers.

The innocuousness of the alleged crime only emphasised the inhumanity of the police’s actions to Mohammad.

“I had never encountered any case that used this method,” Mohammad said, recalling his first thoughts at hearing San and Tambi’s testimony of everyday mundane objects being used as instruments of torture.

“When I met them, they still had bruises, their skin was peeling and I could see the unhealed wounds. It was quite heartbreaking.”

The potent work of Chili Powder and Thinner encapsulates the grim reality of detainees in Malaysia, a country where activists have grappled with the thorny issue of police accountability and reform for almost two decades now.

Beyond the perhaps more visible issue of deaths of unconvicted young men like Kula, there exists a more pernicious and widespread issue of violence within the wider Malaysian penal system. From 2018 to 2020, SUARAM reported a total of 441 deaths in custody, which includes deaths in prisons and immigration centres. This makes for an average of 12 deaths a month over that period.

Only one in four deaths in custody is disclosed by the Ministry of Home Affairs, said Mohammad. The official cause of death determined by authorities is often vague, he continues, with most classified under “medical”, “natural causes” or “unknown”. Family members of the victims, if any exist, are left in the dark on how to pursue further investigation.

A disproportionate number of reported victims are members of the Indian minority. Despite only making up 6.9% of the Malaysian population, Indians account for nearly a quarter of all deaths in custody. This year alone, six unconvicted Indian men have died in police custody.

But with Malays also making up almost half of all deaths in custody, Amin is keen to emphasise this is a Malaysia-wide issue that impacts everyone.

“It’s not an issue of race. This is a fight between the people and police violence,” Amin emphasised. “The violence you see here can happen to anyone, your race doesn’t matter here.”

[The IPCMC is] for the good of all, including the police. It’s not just about [police] misconduct, but their welfare … It’s not supposed to destabilise the country, but rather a safer and stable country

With recurring incidents of deaths, what has grown over the past 15 years is an overwhelming call for police reform. Human rights groups in the country have campaigned for the introduction of the IPCMC since it was first proposed by independent body the Royal Commission in 2005, seeking to introduce a watchdog to oversee the Royal Malaysia Police.

With the landmark change of federal government to the Pakatan Harapan coalition in 2018, their unceremonious collapse in February 2020, and then the rise of Perikatan Nasional government thereafter, the bill has been subject to many changes amidst this political upheaval. Consequently, a watered-down version of the IPCMC, the Independent Police Conduct Commission (IPCC), was tabled in an August 2020 bill.

One of the most crucial differences between the IPCMC and the IPCC is the removal of Section 33 (1), depriving the commission of enforcement powers and limiting their role to recommendations, significantly limiting their ability to challenge impunity.

When asked about the divide between supporters and critics of the IPCMC, Anna Har, co-founder of the Freedom Film Network that released Chili Powder and Thinner, said that the proposed body is treated with suspicion by some, who see it as a threat to the institutions that uphold law and order in Malaysia.

“[The IPCMC is] for the good of all, including the police. It’s not just about [police] misconduct, but their welfare,” she told the Globe. “It’s not supposed to destabilise the country, but rather a safer and stable country.”

“We all have a connection to someone who is in the police force, who really are decent people. We’re not saying that everyone’s bad. We’re just trying to help the government improve its system.”

Hostility to police reform is evident in the response to the film from authorities. After its release, police opened investigations into those involved in its production and dissemination.

Har and Amin, who had their office and home raided by the police on July 2, are currently under investigation under Section 500 of the Penal Code for defamation, Section 505 (b) of the Penal Code for publishing content that might cause public alarm, and the Section 233 (1) (a) of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 for improper use of network facilities.

Shortly after, investigations into Mohammad, as well as SUARAM executive director Sevan Doraisamy and advisor Kua Kia Soong, along with the co-founder of youth-led collective MISI:Solidariti, Sharon Wah, were opened under the same charges.

To Har, it’s clear that Malaysian authorities are tapping into a deeply rooted culture of fear, given the frequent use of legal warfare to suppress expression.

“They’re trying to make us the example of warning others to keep quiet. The police are the hands and legs of people in power,” Har told the Globe.

Over the years, Freedom Film Network has released four films tackling similar themes around police violence. However, Har says this was the first film to trigger an official reaction. Both Amin and Mohammad believe it’s the combination of the graphic reenactment of police misconduct and the testimony of a minor that sparked the strong response.

“I had heard about stories of torture inflicted on adults, but I couldn’t visualise it. It wasn’t that memorable because they were adults, but this was different, this was a 16-year-old boy,” Amin said. “If it’s just images, it wouldn’t have the same impact. The animation made it much more expressive.”

Mohammad believes the film held up a mirror to the police, leaving them uneasy at what they saw.

“The police see it [the film] as too much, it hasn’t been done before where people reenact their acts and illustrate it,” said Mohammad. “The police are seeing themselves being scrutinised. It doesn’t sit well with them.”

While authorities may have hoped to silence the film and its makers, as is so often the case with attempts at suppressing content, their actions have only given the film new life.

As a consequence of the controversy, views of the film on Youtube, which sat at 20,000 on July 1, tripled in just a few days – spurred on by the publicity surrounding police efforts.

“Everyone should watch the film, if you are afraid to share it, then just watch it,” said Har. “They can’t catch 60,000 people.”

Despite the investigations, the creators behind Chili Powder and Thinner remain resilient in the face of efforts to suppress the film.

“To tell you the truth, the police are intimidating, but I’m not going to stop conveying what I feel is right and speaking out against injustice,” Amin confessed.

“I kept thinking, what if this happened to my family?”