Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines are surging ahead of their regional neighbors, with FDI increases of 17, 19 and 20.4 percent, respectively, in 2013, according to Bank of America Merill Lynch

By Matthew Zito

Meanwhile, Singapore continues to receive the lion’s share of total FDI in the region, which last year grew five percent to a net value of nearly US$64 billion. The city-state’s attraction for foreign investors derives not only from its often overlooked manufacturing base, but also as a channel for routing FDI into other locations in Asean.

Based on World Bank figures, Vietnam showed a more modest FDI increase of 6.36 percent year-on-year for 2013. Analysts expect this to spike, however, following Vietnam’s entry into full compliance with the Asean Economic Community by 2015. This will remove virtually all tariffs on goods traded between Vietnam and Asean member nations, as well as various quantitative restrictions and non-tariff barriers. To date, 72 percent of registered capital for FDI into Vietnam has come from manufacturing and processing.

The ten member states of Asean can be divided in many ways: geographically, the bloc is split between continental states like Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia and the archipelagos of Indonesia and the Philippines; culturally, the region is home to the largest Muslim nation in the world (Indonesia), bastions of Buddhism like Cambodia and Thailand, and the Roman Catholic majority of the Philippines; and in economic terms, the GDP of Indonesia exceeds that of runner-ups Thailand and Malaysia combined, and weighs in almost one-hundred times larger than Laos. But it is the region’s growing integration that is drawing the attention of foreign investors. With a milestone target for economic integration fast approaching in 2015, the region is poised to be awash in FDI over the coming years.

In fact, investment into Asean is already at an all-time high, with FDI inflows into the region’s five largest trading countries (the “Asean-5”: Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand) totaling US$128.4 billion in 2013, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch. Of course any discussion of the rising competitiveness of Asean must address the dragon in the room: China. In terms of both total investment and year-on-year growth, these five powerhouses outperformed China in 2013.

Historically, Singapore has been the greatest recipient of FDI in the region, followed at a wide margin by the remaining Asean-5 members and Vietnam. The city-state is also the largest source of intra-regional FDI at 45 percent, while the greatest outside contributors are the European Union (25 percent of total FDI), Japan (13 percent) and the United States (11 percent).

Investment has been variously directed into different sectors based on its country of destination. Whereas in Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam, the manufacturing industry has been the main recipient of investment, there has been a greater emphasis on the services sector in the more advanced economies of Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines.

From a regulatory standpoint, manufacturing is the most liberalized sector for foreign investment into Asean, contrasting with the more stringent restrictions placed on business services, communications and transportation in the region. The World Bank’s East Asia Pacific Economic Update found that Thailand, the Philippines and Malaysia are among the most restrictive countries for foreign equity, while Cambodia and Singapore allow for nearly 100 percent foreign ownership in most sectors.

Asean Economic Community

Asean Economic Community is one element, along with the Asean Security Community and Socio-Cultural Community, of the larger Asean Community initiative targeted for implementation by 2020, as decided upon at the Asean Concord II in October 2003. In 2007, further details for AEC were laid out in the AEC Blueprint, including the now looming deadline of 2015. The Blueprint sets out the intention to “transform Asean into a single market and production base, a highly competitive economic region, a region of equitable economic development, and a region fully integrated into the global economy.”

The first of these goals promises an unrestricted flow of goods, services investment, and skilled labor between member nations, as well as a “freer flow” of capital. Liberalization measures for the free flow of goods, services, skilled labor, capital and investment have already been 85 percent achieved, according to official Asean estimates. Although doubts have been raised as to whether Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam will be able to meet the compliance target of 2015, The World Bank has calculated that Asean’s overall trade costs have come down 15 percent over the past ten years, with intra-regional trade nearly doubling over the same period, to almost US$500 billion last year.

As envisioned by the Blueprint, the achievement of these goals calls for “new mechanisms and measures to strengthen the implementation of its existing economic initiatives; accelerating regional integration in the priority sectors; facilitating movement of business persons, skilled labor and talents; and strengthening the institutional mechanisms of Asean.” To accomplish these goals, the Blueprint sets out various targets for IP, e-commerce, and infrastructure projects by 2015.

AEC is supported by two further agreements: the Asean Comprehensive Investment Agreement (ACIA) and the Asean Framework Agreement on Trade in Services (AFAS). The former includes provisions for the liberalization of FDI using a negative list approach – in which investment is permitted into all sectors not explicitly prohibited by a given signatory country -, and sets out mechanisms for dispute resolution and rule making . Conversely, AFAS provides for the opposite approach, whereby FDI in certain services is prioritized based on their inclusion on a positive list.

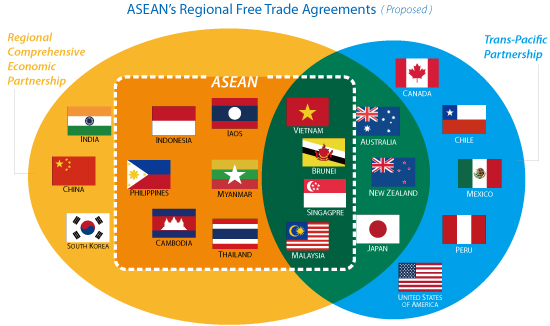

Additionally, several key Asean members (Brunei, Malaysia, Singapore and Vietnam) are also included in ongoing negotiations for the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a U.S.-led regional free trade agreement. The currently 12-member group represents two-fifths of world GDP, including economic heavyweights such as the United States, Japan, Canada, Australia, and Mexico. If ratified, the TPP would entail FTA-style tariff reductions in key economic sectors, in addition to other commitments regarding intellectual property protection, environmental standards, and e-commerce.

Lastly, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) is a proposed agreement for creating a free trade network between Asean and the six countries with whom Asean has existing FTAs (Australia, China, India, Japan, Korea and New Zealand). Unlike the TPP, the RCEP aims to accommodate a broader range of economic disparity between its potential signatories, who account for nearly half of the world’s population and approximately one-third of global GDP.

What is it that makes Asean a preferred destination for FDI?

Demographics

Of especial interest to manufacturers, Asean’s population of more than 600 million is already in the middle of a “demographic dividend”— a period in which the ratio of employable workers rises against the number of dependents. With some 60 percent of the total population of Asean under the age of 35, multinationals like Volkswagen and Foxconn have been keen to take advantage of the labor surplus, especially in light of China having spent its own dividend and now entering a period of demographic aging.

Consumer Markets

Beyond its status as a preferred site for manufacturing, Asean is also witnessing vibrant growth in consumer markets throughout the region. Five of its ten member nations have populations of over 50 million, and the leader among these (Indonesia) has nearly as many people as the next three countries combined. Beyond their sheer numbers, the demographics of these populations are also transforming: Vietnam’s middle class, for example, is expected to increase from two million today to 33 million by 2020.

Investors eyeing opportunities in Asean’s domestic markets would be advised, however, to keep in mind the disparity existing between member states; per capita income among the 52.8 million inhabitants of Myanmar, for example, is only US$900, whereas the equivalent figure for the 5.3 million Singaporeans is US$50,000.

Treaty Network

International treaties form the basis of Asean. In addition to the tariff reductions between member nations as part of the Asean Economic Community (see below), the members of Asean are also signatories to free trade agreements (FTAs) with some of Asia’s biggest economies — China, India, Japan, and Korea — and commonwealth nations Australia and New Zealand. As one such example, the China-Asean FTA ratified in 2011 has reduced tariffs to practically zero on 90 percent of goods traded between the two jurisdictions. For Asean-based manufacturers, the agreement facilitates access to China’s gargantuan domestic market, expected to grow to 600 million by 2020, up from 250 million today.

Taxes

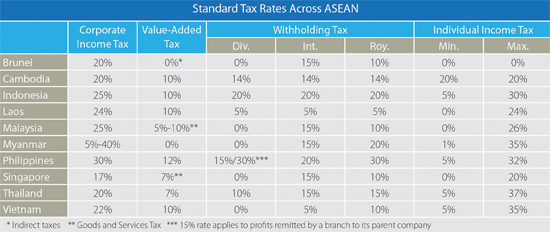

Tax implications for foreign investment into Asean vary considerably between specific countries. Although the AEC Blueprint identified the removal of double taxation between Asean countries by 2010 as a top priority, several members have yet to meet this target; notably, Cambodia has yet to ratify a DTA with any other nation. Meanwhile, the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT ) scheme has long since removed customs tariffs on 99 percent of goods traded between the Asean-6.

At present, tax rates vary between Brunei’s total absence of individual income tax, to Thailand’s maximum bracket of 37 percent; and from Singapore’s ultra-low 17 percent corporate income tax to Myanmar’s exacting rate of 35 percent for some foreign entities. In general, Asean members are concentrated toward the lower end of the World Bank’s “Ease of Paying Taxes” rating, with Singapore, Brunei, and Malaysia being exceptions to this trend.

This article was first published on Asean Briefing.

Dezan Shira & Associates is a specialist foreign direct investment practice, providing corporate establishment, business advisory, tax advisory and compliance, accounting, payroll, due diligence and financial review services to multinationals investing in emerging Asia. Since its establishment in 1992, the firm has grown into one of Asia’s most versatile full-service consultancies with operational offices across China, Hong Kong, India, Singapore and Vietnam, in addition to alliances in Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines and Thailand, as well as liaison offices in Italy and the United States.

For further details or to contact the firm, please email info@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com.