Editor’s note: The spread of HIV-AIDS across Southeast Asia has been devastating. For many who have been diagnosed over the years, lack of access to affordable or effective treatment can leave them living out a death sentence denied those in the wealthier West. And even for those who are able to receive the treatment they need to live long and fulfilling lives, the weight of shame brought to bear on them by a society that blames them for their sickness can be relentless. But while increased testing and less debilitating treatments have massively reduced the rate of HIV infections across the region, the road to recovery has been a long one. In July 2008, Southeast Asia Globe visited a Buddhist temple in Thailand dedicated to relieving the suffering of those living with HIV and AIDS – by relying on the steady tread of tour groups through the makeshift hospice. Now, for the first time, you can read their stories online.

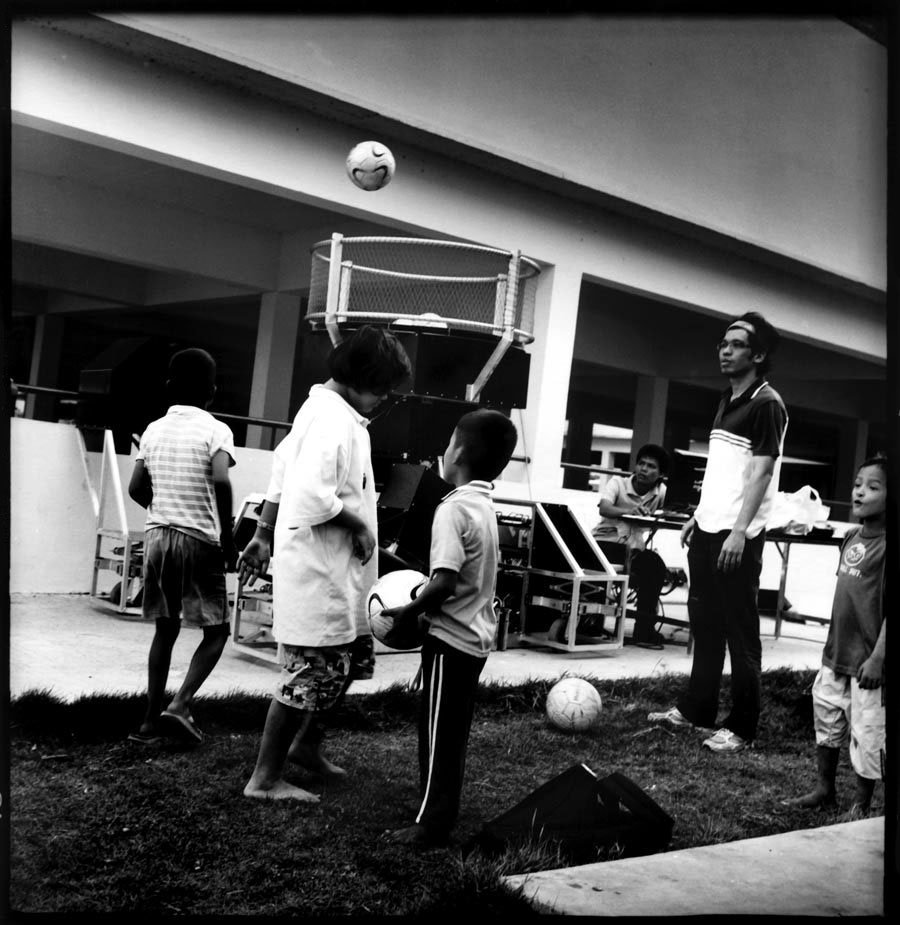

The Soccerbot is a computer-controlled training machine that can shoot footballs at speeds of up to 90km/h. With tireless accuracy it can do low passes, curved shots and corner kicks. It is priced at about $160,000 and only one has been made. Today this prototype sits outside an orphanage for HIV-infected children in central Thailand, spitting out footballs with a force that could lift the residents off their feet.

The orphanage is part of a charitable empire built by Alongkot Dikkapanyo, 54, a celebrated Buddhist monk who began caring for AIDS patients in 1992, when most of his compatriots still shunned them. His empire has two parts: this remote, 1,200-acre complex, which is home to more than 1,000 children, including many HIV-positive orphans; and Wat Phra Baht Nam Phu, or “the temple of Buddha’s footprints,” built into a parched hillside 90km away, where about 200 HIV-infected adults live and about 10,000 have died. Across Thailand, the temple’s name is synonymous with suffering and death, an image that has allowed its abbot to raise the equivalent of millions of dollars.

Antiretroviral (ARV) drugs, which allow HIV sufferers to live longer, now threaten to undermine this fundraising rationale and shake up the temple’s murky finances. Not even the inventor of Soccerbot can quite understand why the abbot bought it. “I came here expecting to see a team of 30 players,” says Puttachai Rattanalangkan. “But there’s nobody. Just these kids.”

Donations to the temple are tax free and come mainly from tourists, Thais and westerners, who visit the temple in their thousands every week. Today, the resident guide Max, 37, who is HIV-positive, leads a group of middle-aged Thais to the first stop on the tour: the Life Museum. “Take a look inside,” he urges through a megaphone. “You don’t have to take off your shoes.”

Inside are dozens of mummified corpses donated by dead AIDS patients. These illustrate “how death affects all of us, leading us to the truth that in life we must do good for others”, says a sign. One insect-nibbled body still has two globes of silicon suspended from the chest by skeins of flesh. A sign lists the owner’s former occupation as “Singer, Sex Worker (Lady Boy)”.

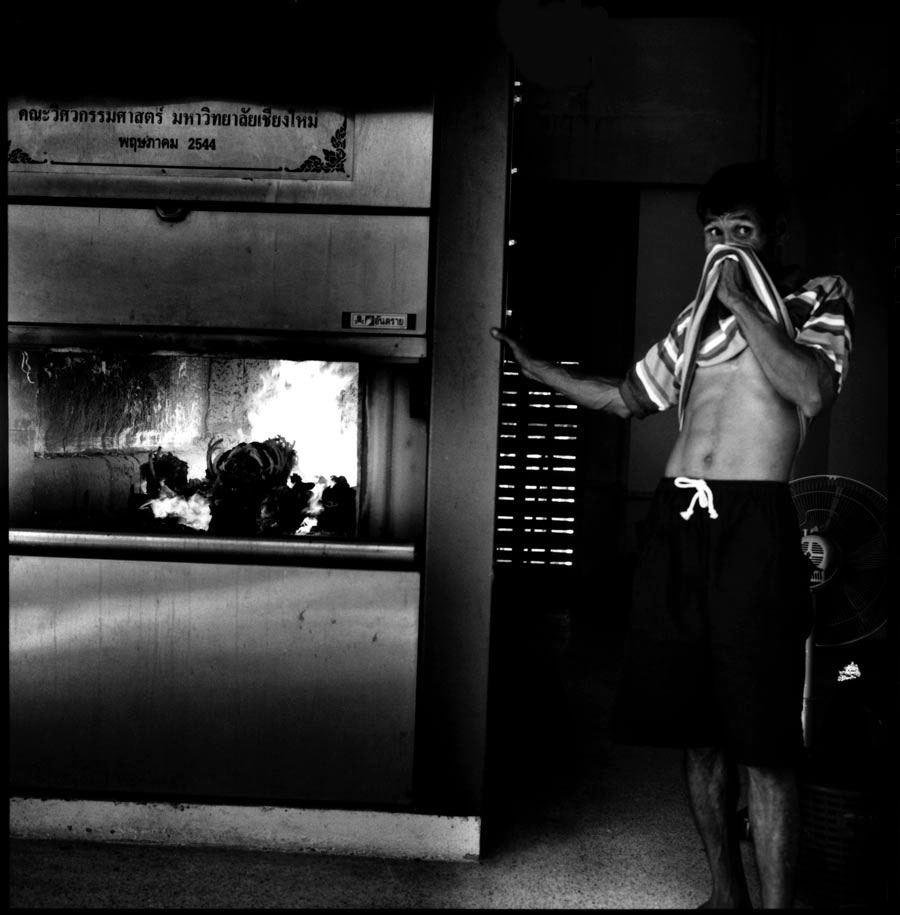

his face during a cremation. There are

now eight incinerators at the temple’s

crematorium. Photo: Agnes Dherbeys

Soccerbot, a football training machine,

outside the orphanage for children

with HIV. Photo: Agnes Dherbeys

We pass the crematorium – the temple has eight incinerators, notes Max – and a garden of crude sculptures made from the pulverised bones of more dead patients. Then we stop outside a one-storey building. “This is for people who are in their final stage,” announces Max. “If you want to take their photos, please ask them first.”

There are 31 men and women in the ward. They ignore the tourists. Some totter about in adult nappies, their faces smeared with talcum powder to hide cancers and other skin diseases. Others are curled up in bed, lost in pain and torpor; one man is being eaten to death by a rectal carcinoma. Some patients are blind, while 11 others – including five skeletal forms in a poorly quarantined side-room – are battling tuberculosis. Stray cats and dogs stroll at will through the ward.

The tourists file out. The final stop is a large Buddha statue surrounded by a wall of sandbags; these contain the ashes of the dead, hundreds and hundreds of them, vainly awaiting collection by relatives. Then the tourists are given Buddhist pamphlets and an opportunity to donate. A large party of school-children is right behind them.

Death and tourists: these have been constants for Michael Bassano, a Catholic priest from upstate New York who is the temple’s longest-serving volunteer. He is a fit-looking 59-year-old who has spent four years caring for HIV patients – bathing their fragile bodies, massaging their diseased skin, holding them in their final moments. “It doesn’t matter what their history is, what [sexual] orientation they are – they’re one of us,” he says. “They’re human beings. Let’s treat them as though their life has value and meaning.”

“Yes, people still die of AIDS, but with this new medicine we can encourage them to keep on living. This is a temple of life, not of death”

Volunteer Michael Bassano

At least one million Thais have been infected with HIV since the first reported case in 1984. More than 400,000 have died. Thailand was one of the few developing countries to successfully curb its epidemic with awareness campaigns, and later pioneered the widespread distribution of cheap ARVs. In the 1990s, up to 100 patients died at the temple every month. By the time Bassano arrived in 2003, there were less than 15 deaths and ARVs soon reduced the toll to single figures. Bassano feels it’s now time to change the temple’s morbid image. “Yes, people still die of AIDS, but with this new medicine we can encourage them to keep on living,” he says. “This is a temple of life, not of death.”

Some patients come to the temple voluntarily. Others are abandoned like rubbish. One night, recalls Bassano, a car with its lights off pulled up at the temple gates and a man was pushed out. He died two days later. He also remembers a patient who had been so neglected at home that his left leg had been paralysed for seven years. “One day he said to me, ‘I want to walk’,” says Bassano. And with the priest’s help he did. “He walked every day for the next five months. Then the disease hit his digestive tract and he was gone. But for a while he was the happiest man alive.”

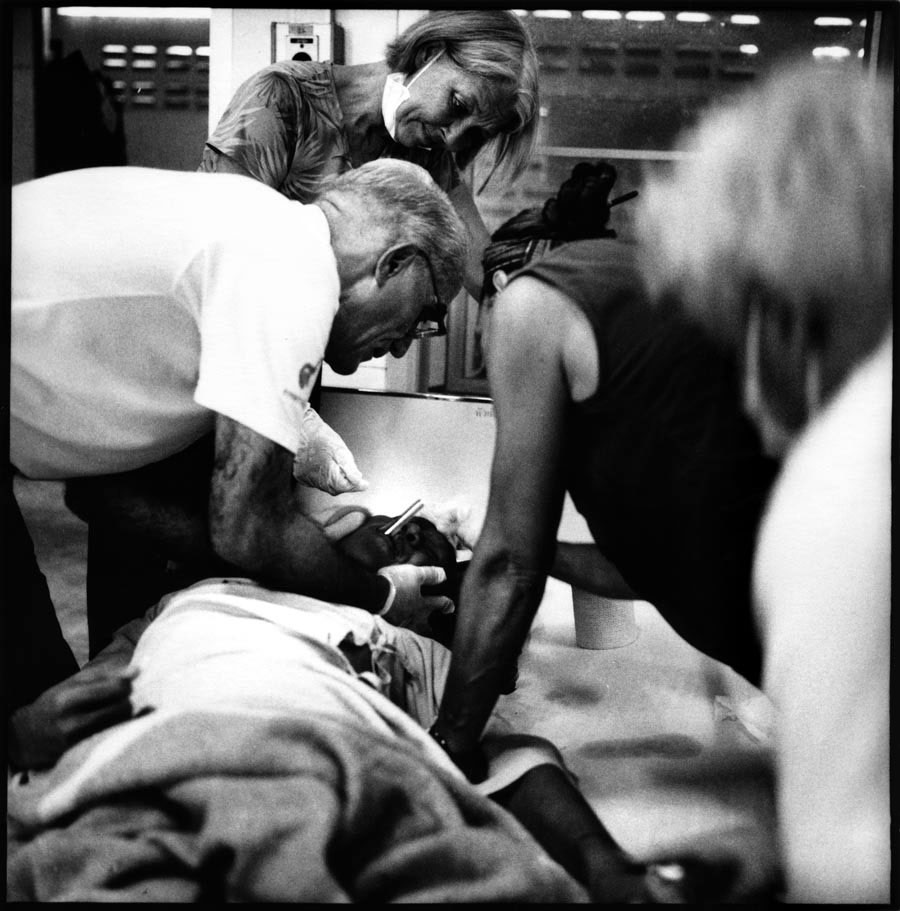

Clockwise from bottom right: staff attend to patient Chan, so ill that he has lost the power to speak. Chan died five months after arriving; monks pray in front of a large Buddha statue; tourists arrive at Phra Baht Nam Phu. Photos: Agnes Dherbeys

This inspired Bassano to “do the simple things that bring people back to life”. A 28-year-old woman with HIV called Amphan arrived six years ago and fell in love with another patient. When he died in 2003, she threw herself from the top of a four-storey building, shattering her pelvis. She has been bedridden ever since.

Every day the priest took her in a wheelchair to the Life Museum, where the corpse of her boyfriend is preserved. “She finds it reassuring as she talks to him,” says Bassano. “Otherwise she sits in that bed all day and nobody talks to her.”

The Thai staff oversee the suffering but are “not really hands-on”, says Bassano. He partly blames the Buddhist notion of karma. Patients also believe that HIV is a karmic death sentence. Chukiat Sungsorn, 51, a former engineer, was shocked to discover he had the disease after taking a blood test during an AIDS awareness campaign. “My wife had it but never told me,” he says. “I don’t know how she got it.” And he never asked. “I wasn’t angry. Bad karma is following me. I did something bad to my wife in a past life, so I must pay for it in this one.” Chukiat looked after her at home until she died and, when neither family nor friends would do the same for him, took himself to the temple six years ago.

“I only stay here because society doesn’t want me; people are disgusted when they find out I have HIV”

Patient Sanoer Soiwan

The staff are also poorly paid (about $109 to $218 a month) and trained for what is gruelling work. “I work 12 hours a day,” says Wilaiwan Khantiwong, 26, the slender, no-nonsense woman who runs the ward. “Often I can’t do much for the patients and I feel like giving up. But if I leave, who will take care of them?” Wilaiwan is a licensed nurse who has worked here since she was 17. “I do every job, from cleaner to doctor,” she says. Today, she carries not a stethoscope but a tube of Toblerone, a donation from a Swiss tourist. Paracetamol is her strongest painkiller. “We have some morphine, but it might have expired by now. Without a doctor around, I don’t dare use it.”

Ideally the temple should have two doctors and three registered nurses, says Bassano. The last doctor to work here was a Belgian volunteer named Paul Yves Wery, who left in 2004. He wrote a parting account of his years at the temple, describing it as unsanitary, ill-equipped and mismanaged. After Wery’s book was published, all foreign volunteers except Bassano were asked to leave.

These days, patients see a doctor only once a month when they are taken to a hospital in the nearby town of Lopburi for a check-up and a fresh supply of ARVs.

Many HIV patients get AIDS dementia, a degenerative brain disorder that can make them moody, incoherent or violent. Due to the lack of staff, unruly patients are sometimes kept in steel cages next to the shower area. When I visited, one cage was occupied by a patient who has been ripping up the ward’s mosquito nets. Some people are caged for their own protection. One dying woman screamed so much she was beaten and gagged by other patients.

Fewer than 17,000 infections were reported in Thailand in 2006, compared to 143,000 infections in 1990, according to UNAIDS. But the infection rate could climb again. HIV prevalence among intravenous drug users and male sex workers remains high, while condom use among Thai teenagers is shockingly low. Thailand must now try to re-educate the public about a horrific and incurable disease.

The temple claims to be doing just that. But could its tours also be sustaining the prejudices that make it so hard for HIV sufferers to remain in Thai society? Bassano believes so.

“Some kids come through with their hands over their mouths,” he says. “Sometimes they pass through this 33-bed ward without even saying hello.” A patient called Sanoer Soiwan, 39, a former grilled-chicken vendor, hates the tours. “I only stay here because society doesn’t want me; people are disgusted when they find out I have HIV.” After eight months at the temple, Sanoer feels healthy enough to seek work outside, but nobody will hire him. “I think all day and all night about how I can get out of here.”

As a rule, only adults live at the temple. About 1,300 children live on a separate compound called the “second project”, which includes the orphanage. But not all are orphans – many are children of poor local farmers – and only 140 have HIV; about the same number of infected adults live here too. Most buildings on the second project’s vast compound seem deserted and in disrepair. The Soccerbot sits outside a building that houses 74 orphans. Children – some emaciated, some as young as three – wander the cheerless hallways or wordlessly rummage through boxes of bric-a-brac.

The lone adult supervisor is Nuanchan Hassanam, 43, a weary-looking woman with a “Love Forever” tattoo on her arm – an unwelcome reminder of the estranged husband who gave her five children and herself HIV. Nuanchan says raising orphans is like “trying to keep crabs in a bucket”. They are short on staff and basic clothes. “The children need vests, underwear and shoes,” she explains. So why has $150,000 been spent on a football machine? “I don’t know,” she shrugs. “The abbot wants the children to exercise.”

Famous Thai monks have an almost rock-star status. They are courted by politicians and celebrities, and lavished with donations. They generally prefer audiences to interviews. So, one Sunday morning, I join dozens of tourists at the temple kneeling before Alongkot in a room crowded with Buddha statues. Many people clutch photos or amulets of him to sign or bless. His words are sometimes lost in the crash of donation boxes being emptied in the room.

Alongkot reckons about four million people have now visited the temple. He defends the tours, claiming they raise awareness and improve patients’ self-esteem.

When Alongkot took in his first HIV sufferers, it was an act of compassion before its time. Sixteen years later – with hundreds of thousands of Thais visiting and the temple’s coffers spilling over – the patients seem overlooked, even as their very public plight keeps the money rolling in.

With ARVs getting cheaper and more effective, the strategy might not last much longer. “How will they get money if people look healthy?” Asks Bassano. “People are getting better. You can’t stop this process. The ARVs are here to stay.”