Experienced educator and senior partner at Yejj Consulting, Ali Copple explains how to get the most out of Cambodia’s international schools

What was the private education landscape like when you arrived?

I was hired initially to tutor World Vision children – this is in 1990 – and within a few weeks they thought there are other international kids here too, so I was hired to start ISPP [International School of Phnom Penh]. It was a home school at the time. In our first year we went from six at the beginning to 33 at the end of the year, and it just grew. It was mostly NGOs and some embassies that had families, not a lot of Cambodians.

How would you describe the international school options now?

It’s not changed as much as I would have thought over the past four to five years. There are probably – we think about tiers – there are probably two or three in the top tier, in the second tier maybe three to four, below that are still good schools, maybe another four. There are also schools that are run as businesses. Lots of these schools hire customer service people, and their job is to sell the school to get customers in, and that’s not wrong as long as they’re being authentic about what they’re saying about the school.

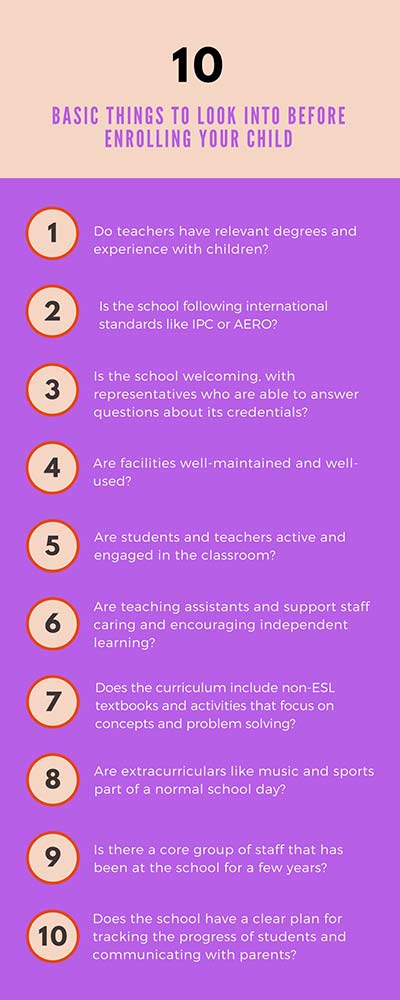

How can parents evaluate a school before deciding to send their kids there?

I think that as a parent walks in the gate their impressions are really going to help them know if the school is what it claims to be. Is it nice? Is it welcoming? Is it somewhere you would like to stay yourself? Often the reception areas are very nice, but once you get past that, you need to see the rest of the school. What do you hear? What do you see? When you go into the classrooms are the children engaged? Are they busy? Or are they sitting very quietly for long periods of time – that would be indicator number one that you don’t want to be at that school. Can you see that there is mutual respect between the children and the adults? I would recommend going for almost an hour to sit quietly in the back of classrooms – you can learn a lot about a school that way.

How do you know if you have found the right school?

I think your child is the best indicator for you. Is your child happy to go to school every day? If you have a question, what happens? Can you go see a teacher? What kind of communication are you getting from the school? I think you can tell [for] yourself if you go into the school, like when you buy a used car – you kind of know you made a mistake because you got pushed into something.

A helpful guide

Teachers

A school would ideally have teachers with education degrees, but if a school employs some teachers without degrees it does not need to be a deal breaker. If teachers have degrees in other fields related to working with children, or are in the process of earning their teaching certification, that’s a good sign. “It is an indication that the teachers… are lifelong learners as well,” said Ali Copple, an education consultant based in Phnom Penh. “Often in middle-tier schools, there will be lots of teachers hired with TESOL and TEFL certificates, which is great for teaching English but not for a holistic curriculum,” she added. Staff turnover is to be expected at an international school, but if it happens too often that is a clear sign that the school is not going to offer a stable learning environment.

Curriculum

As with teachers specifically trained to teach English, some schools will build their curriculum by cobbling together ESL programmes, making it seem like a general curriculum. However, without a holistic curriculum the school is less likely to have accompanying activities that imbue critical-thinking and problem-solving skills to students. Even middle-tier schools should at the very least be able to explain what standards they follow and what programmes they use in their curriculum. If the textbooks for subjects like maths and science are all ESL-oriented, that is a strong sign that the school is not following a real international curriculum. “We probably have too many [self-proclaimed international schools] that are not actually international schools, which can be confusing for parents,” Copple said.

Accreditation

Any top-tier school will have international accreditation that makes its qualifications applicable to other international schools or universities. As with the qualification of teachers, a school does not have to be accredited to be a good international school, but it does need to have a system ensuring that students are becoming critical thinkers and independent learners. “Children that go through an international programme, even if it’s not accredited yet, they are learning those skills, they are learning how to work in a team and a group, they’re not thinking only about what somebody tells them to do,” Copple said. “If children are actually going to an international school, they will be fully equipped to study outside of the country.”

Facilities

The quality of a school can often be seen in the quality and amount of learning materials in classrooms, as well as other areas where students can play, learn or exercise, according to Copple. If playgrounds and in-class resources look well-used and well-maintained, that is a good sign, as is having lots of student work hanging up in halls and classrooms. For younger students in particular, there should be lots of practical things in the classroom for them to use and explore. If the school has a range of age groups, there should be different areas for playing or staggered break times. Shared spaces such as cafeterias, gymnasiums, auditoriums or computer labs should be well-used and hygienic.

This article was published in the October edition of Southeast Asia Globe magazine. For full access, subscribe here.

Read more and Discover the SCIA Education Experience here.