In Singapore, a country with almost 14,000 food and beverage services, “Have you eaten?” goes deeper than small talk. It’s a way of expressing care and concern, of asking how you are in a city-state where openness around mental health is still in its infancy.

In Divaagar’s kitchen, the words stretch boldly across a wall painted in pale lilac. They overlook a fridge filled with pixelated food and friendly chatter, a frying pan cooking dinky painted eggs and a “window” screen showing a bright, anonymous city-scape.

The Singaporean visual artist’s ‘Model Kitchen’ is the opening work in MENTAL: Colours of Wellbeing, a collaborative exhibition between the Lion City’s ArtScience Museum and the Melbourne Science Gallery which launched on 3 September. The exhibition aims to showcase different stories across the mental health spectrum through the interplay of art, science and technology.

Divaagars’s kitchen is a hyperrealistic caricature of the family hub where eating, food preparation and conversation take place. The kitchen was a “source of conflict” for the artist growing up. It was also a spot where he learnt recipes, overheard family gossip and learnt about his Indian Tamil and Malay heritage.

“Food, and food preparation, over the past couple of years especially, is quite intimate to everyone,” said Divaagar, referencing the claustrophobia of pandemic lockdowns. “I thought that would be an easy entry point.”

There are over 430,000 adults living with a mental illness in the city-state, according to a 2021 release from the Institute of Mental Health. This is almost 9% of the total estimated adult population. But despite government efforts, longstanding cultural taboos and societal pressures have stymied conversations. Now, artists and scientists are speaking out to tackle cultural and societal stigmas around mental health and call for greater resources and support.

ArtScience Museum Director Honor Harger believes a combination of global events and rising local demand made the timing of the exhibition’s Singaporean launch critical.

“We already knew from our own observations of society that mental well-being was becoming an urgent question for young people in Singapore,” she said. “To reflect on the pandemic, plus the overarching crisis of climate change, the new crisis of the war in Ukraine has done to our collective mental well being could not be more timely.”

Ryan Jefferies, Melbourne Science Gallery’s Creative Director, agrees that the health crisis helped influence a closeness of shared experience. The chance to expand the original iteration of the Australian show, which ran from January to June, was an opportunity to take this closeness to cross-continental levels.

“We’re very interested in global perspectives on these big issues,” Jefferies said. “This was a real opportunity to reflect on mental health in Asia Pacific, in general.”

Local resonance was important. Only 17 works out of 21 works from the original Australian iteration were adopted for the ArtScience Museum. Meanwhile, seven additional artworks – five from Singapore, and two from the wider Southeast Asian region – were added.

One Singaporean artist is Tan Yang Er, also known as ‘Yangermeister,’ who dove into her own psychotherapy journey for her collaboration with creative technologist Akbar Yunus. In ‘Scenes from Therapy,’ animated neon wigs sway jerkily on a chequered floor. Another sits rigid on one of two reflective chairs formally facing each other. Named Breakthrough, Confusion, Static, Clarity and Exhaustion, the wigs represent the various stages of the therapy process.

Sharing such intimate work gained mixed reactions. The artist described being targeted online.“I’ve gotten some very negative comments before,” Tan said. “Saying it[‘s] narcissistic when the work is so about yourself”.

“But as artist[s], we’ve got to be brave. Honesty is liberating.”

Efforts have been made at top-level to make this honesty easier. Senior Minister of State for Health, Janil Puthucheary, announced plans to establish a national mental well-being office in March. The nation’s first Wellbeing Festival, spearheaded by the Singapore Tourism Board debuted the nation’s first 10-day Wellbeing Festival in March, showcasing wellness activities and experiences including yoga and cooking classes.

But Allison Heilizcer, a therapist who has been working in Asia for over a decade, notes that behind the increased attention on wellbeing, lies a worrying lack of information.

“There is a dearth of studies and data on mental health in Asia,” she said. “There is also a stigma around getting mental health care, and the cost is out of reach for most if they’re paying out of pocket.”

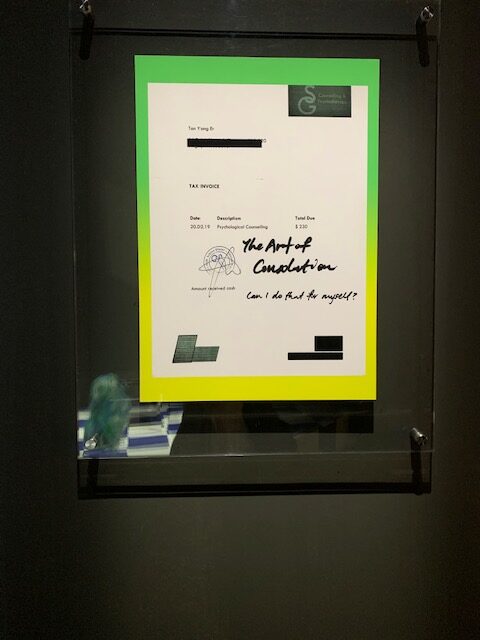

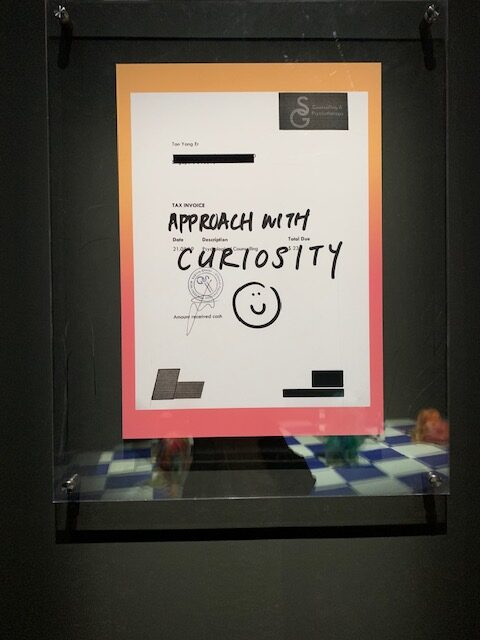

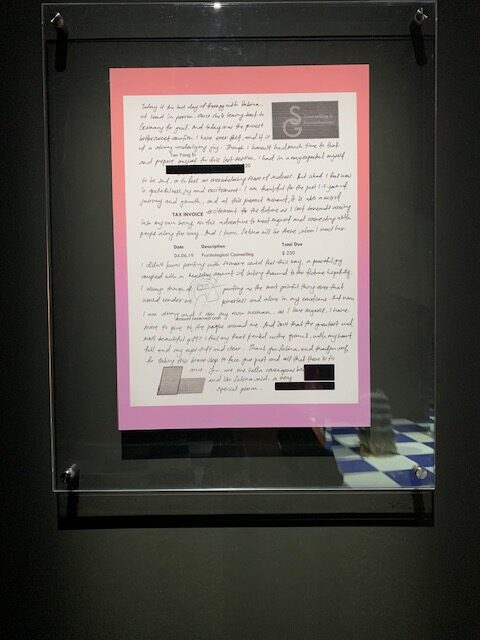

Tang Yang Er annotated receipts from her personal therapy sessions as a diary of her own mental health journey.

On the wall of Yang’s ‘therapy room,’ hang framed, annotated receipts from her sessions, a foreboding reminder that support in the Lion City can be expensive. Fellow exhibitor Dr. Emma Burrows, points out that it is not just price, but lack of resources that can render support inaccessible.

“In Singapore, there are 2.3 psychiatrists for every 100,000 people. In Australia, there are over 14. We’re talking about access to this sort of support,” Burrows observed.

‘Wheel,’ the neuroscientist’s collaboration with Japanese-Australian artist Hiromi Tango, explores the link between exercise and mood. For Burrows, the bridging of art and science breaks down interdisciplinary siloes and also brings the “indecipherable” language of science to the mainstream.

“[As] a scientist in a museum it’s a new way to explore making the invisible visible,” Burrows said. “Everyone should have access to information. Especially when it’s about our health.”

The very visible ‘Wheel,’ is a vibrant human treadmill in rainbow colours, emphasising the critical link between exercise and mood. But the joyfulness has a sober side, according to Burrows. The roller could also represent the incessant grind of the rat race. The live tracker and digital platforms giving runners feedback in real time emphasises the importance of cheerleaders but also the pervasive influence of social media. Equally Burrows stresses that behind the growing vogue for “wellness” is a serious reticence to progress to medical help.

“There’s a lag time in getting help,” Burrows said.“When people with depression, wait for a year. People with OCD wait for 11 years. People are not seeking out help. I love that our exhibition is joyful, but there is a serious problem under that.”

Heiliczer agrees that there is a skewed focus on physical over mental healthcare in Asia, not just from the public but also from professionals.

“Physical health is prioritised over mental wellbeing especially in public healthcare systems. This is an unfortunate irony as mental wellbeing is very much connected with physical wellbeing,” she said.

According to Alecia Neo, an artist whose work focuses on long-term collaborations with individuals and communities, Singapore is still a country where “there is a lot of emphasis on family being the first line of defence” when it comes to mental healthcare. The nuclear family unit has led to a “squeezed generation” of female caregivers in Singapore, supporting elderly parents who have moved in and children.

“That’s one thing that can definitely be worked on. There needs to be… better systems of care,” Neo said. “Not just family. Because families are becoming smaller.”

Neo’s ‘Between Earth and Sky,’ filmed 12 participants, seven caregivers and some of their charges, as they each perform a self-choreographed dance. The moves show the rituals and rawness of receiving and providing care. Hanging above the screen are kites made from the caretakers’ clothes.

The work emphasises the mental stress of not only those reliant on family members for daily care, but also those providing it, something Kimberly Wong, research executive at AWARE, underlines as an urgent and under-reported issue.

“Caregiving is often physically, mentally and emotionally taxing,” she said. In a 2019 survey of family caregivers by the non-profit organisation, two-thirds of respondents reduced their working hours or quit their jobs to accommodate caregiving, putting them under significant financial strain.

Wong suggests that the government should consider the introduction of a caregiver support grant, using the average salary of professional care workers as a reference point. She also believes community networks can provide vital support.

“Community-based formal care services should be made more available and accessible. Such services help in the redistribution of care such that family caregivers are not solely responsible for caregiving,” Wong said.

The importance of mental health support for those in supporting roles extends further than the family unit. In August, the Ministry of Health launched a chatbot app to help tackle rising complaints of stress and burnout amongst teachers. The app’s robotic responses hit the wrong note with some users, but Neo believes that there is a wider underlying issue.

“If class sizes don’t change, teachers are still overwhelmed. They still can’t give the care. Fundamentally, the values have not shifted,” she said.

In Myanmar, where mental health resources are limited and account for just 1.4% of total public sector spending, according to 2020 UN research, the burden of care also often falls on family. Burmese artist Shwe Wutt Hmon’s photographs document her sister Ky Kyi Thar’s experience living with Schizophrenia. A trained artist, Ky Kyi Thar painted over her sister’s photos, bright abstract colours contrasting against their black and white realism. The siblings’ partnership shows the stark everyday of living with mental illness and the empathy of recovery.

Back at Burrows’ and Tango’s Wheel, the tracker has clocked up over 377.74 kilometers since its setup at the ArtScience Museum. The aim, Burrows quips, is to beat Melbourne’s record of 18,000. As the world shifts from the heart of the global health crisis to economic ruptions, Sta are in a similar race, not against each other, but against the rising urgency of a mental health crisis, swelling despite the well-intentioned efforts of government initiatives.

But for Burrows, the immediacy of audience reactions and engagement is its own milestone of progress, and her own mental health boost.

“I work with the brain and a lot of the challenges we experience with brain conditions probably won’t be solved in my lifetime. I guess it’s a dopamine hit, seeing people enjoying, laughing at the exhibits,” she explained.

As these visitors leave Divaagar’s kitchen, another bold sentence painted on the wall guides them on their journey.

“How are you?” it says.

Photos and videos by Amanda Oon for Southeast Asia Globe