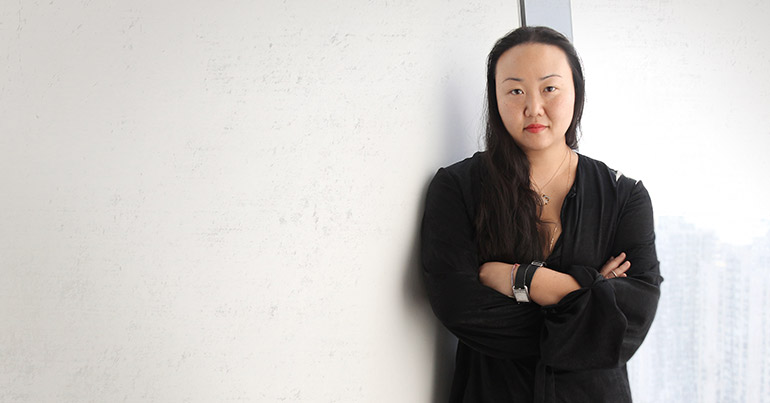

Ahead of her appearance at the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival, the US writer opens up about her searing account of sexual abuse and self-harm in her Booker Prize-shortlisted novel A Little Life

In the haunting expanse of her Man Booker Prize-shortlisted novel, A Little Life, US writer Hanya Yanagihara drags her readers into a world of sexual violence, self-loathing and fractured glimpses of aching beauty.

From its beginning, following four friends from a Massachusetts liberal arts college trying to scrape together a living in the artistic underbelly of New York, the novel slowly distorts around the weight of one character’s unbearable past.

This is Jude St. Francis, an up-and-coming lawyer of frankly absurd talent, whose childhood filled with sexual abuse and betrayal bleeds through the book’s pages as the reader presses deeper into the early years of his life. Within these moments are some of the scenes that polarised readers and critics alike with their graphic depiction of rape, paedophilia and unrelenting violence.

A cipher even to his closest friend, Willem, the now-crippled Jude struggles to overcome the warped lessons of his childhood dragged from motel to motel by the lecherous Brother Luke, habitually resorting to intense self-harm behind his friends’ backs.

Speaking to Southeast Asia Globe, Yanagihara explained her fascination with the darkest expression of one person’s power over another. “I’m interested in it because it’s the ultimate misuse of power,” she said. “All art is interested in inequitable relationships: between two people, or between man and the state, or between man and nature.”

A little life lost

It is not the first time that Yanagihara has been drawn to vivid depictions of child abuse. Her first novel, the similarly acclaimed The People in the Trees, drew inspiration from the life of Nobel prize-winning medical researcher and convicted child molester Daniel Carleton Gajdusek.

Written as the memoirs of one Norton Perina, a similarly afflicted researcher trying to wrest the secret of immortality from an imagined Micronesian tribe, the good doctor grapples with his own sexual desires in a culture where the gang rape of a ten-year-old boy is considered a central part of the tribe’s identity. Although told in the same subjective tone as Nabokov’s Lolita, a novel Yanagihara draws upon heavily, the author herself is firmer in her repudiation of the book’s central relationship.

“An adult who abuses a child has on his side physical strength, intellectual dexterity, and authority,” she said. “No matter what he may say, it’s not a relationship – it’s an exercise in tyranny.”

Unsurprisingly, the act of writing some 734 pages of violence, grief and degradation for A Little Life did not leave Yanagihara unscathed. Working by day as the editor of travel and lifestyle magazines in New York, she struggled to keep the story from seeping through into her own world.

“I can’t say that the book didn’t first creep, and then barge, into my own life,” she said. “But I think it would’ve occupied far more of me had I not had a day job I could go to four days a week. It was both relaxing and reassuring to know that I had eight or nine hours a day to spend outside the life of this book.”

Love in a man’s world

As the four central characters stumble through their halting transition into adulthood – achieving, to a man, wildly improbable success in the process – the novel unflinchingly examines the four friends’ inability to communicate the deep-seated insecurities that gnaw at them. It is this, perhaps, that makes Jude’s self-loathing more viscerally upsetting – even after a botched attempt at self-harm almost costs Jude his life, his closest friend is unable to confront him about the depression that clearly eats away at him. According to Yanagihara, this reticence to express vulnerability is still very much a symptom of male friendship ideals rooted in an earlier time.

“I assume it will change, but change will be slow,” she said. “I know a few people my age – I’m 41 – who are trying to teach their young sons that they have available to them – and a right to – the full range of human emotions, and that voicing, much less feeling, any of them is still compatible with maleness. They all say how difficult it is, and how often they find themselves falling back on old lessons about what a boy should and shouldn’t express.”

Yanagihara said that dealing with this fundamentally limiting perception of men as bastions of stoic fortitude was essential in addressing long-established inequalities between the sexes.

“If men are given permission to discuss shame, embarrassment, and vulnerability… it makes things better for women as well,” she said. “In this book, and in life, the characters’ anger is, often, the manifestation of some other, inexpressible emotion.”

Identity crisis

One of the most immediately apparent leitmotifs throughout Yanagihara’s latest work is the fluid nature of identity. For J.B, a Haitian-American artist whose unyielding self-confidence borders on the narcissistic, his race is initially introduced as a key element in a performance he has maintained since his earliest days at primary school, convincing his white classmates he has risen from the poverty of a broken home.

For aspiring architect Malcolm, his affluent upbringing – and the privilege his family’s wealth grants him – conflicts with his own ingrained understanding of what it is to be black in America. With identity politics increasingly becoming a cornerstone of US national discourse, Yanagihara’s cross-examination of the labels we assign those around us is a much-needed reminder of just how far those boundaries can be pushed.

“All of these characters chafe at the identities that have been assigned to them,” she said. “All of them try to subvert or transcend them. And all of them come to realise that it’s near impossible – society categorises us because history categorises us. And this has always been the case: depending on who you are and where and when you live, what you are makes some opportunities possible and others not.”

For Yanagihara, challenging that status quo is an essential part of what she tries to accomplish through her work – though she acknowledged it was often an uphill battle.

“I’m not sure there’s much use in trying to avoid certain kinds of categorisation,” she said “The thing that’s important now is for us to realise – both in art and in the world at large – is that all of those categories are, in fact, terrifically elastic.”

For her critics, though, that elastic can easily be stretched to breaking point. Perhaps most divisive for critics and fans of A Little Life is Yanagihara’s representation of homosexuality. As in The People in the Trees, the central homosexual relationships in A Little Life are viewed predominantly through the prism of paedophilic grooming and brutal domestic violence. Also troubling, the one relationship in which Jude finds true happiness – a relationship his doting partner refuses to identify as homosexual – is cut short in a fresh wave of disaster that verges on the sadistic. Coming as it does from a heterosexual author, critics are split on whether the novel’s handling of gay relationships is a refreshing refusal to cleave to easy categories or a regressive litany of guilt, disease and denial.

Death rites

In a book of obscene sexual abuse, domestic violence and self-harm, it is a testament to the strength of Yanagihara’s writing that the scenes that leave the greatest impression are not those dealing with the horrors of life but grieving and loss. Early on in the novel, the death of Willem’s disabled brother unfolds with a slow inevitability that mirrors Jude’s own inescapable descent into self-harm – as well as greater tragedies still to come. When asked about conflicting depictions of mental illness and death across the world’s literature, Yanagihara was quick to challenge the West’s language of loss in the face of tragedy.

“I think it’s more that the West and the East have such different approaches to death,” she said. “It’s not that one mourns more deeply than the other, but many Asian cultures, and many Middle Eastern ones as well, have a language, a ritual, for death. I’m not talking about specific religions; I’m talking about specific cultures.”

This, perhaps, is part of the reason behind the book’s unflinching portrayal of the depths to which humanity can sink. By refusing to shy away from even the most graphic details of violence and humiliation, Yanagihara forces us to confront our own refusal to discuss fundamental truths about the world in which we live – and listen for the silence of those trapped beyond society’s most visible spheres.

“In the West, we often pretend it’s not going to happen,” she said. “But throughout much of Asia, there’s a sense that death is not shameful or a topic to be avoided in conversation – it just is. There’s something comfortingly matter-of-fact, something reassuringly, resolutely, un-mysterious about that philosophy.”

The Ubud Writers and Readers Festival will run from 26 to 30 October. The full programme and lineup are available at http://www.ubudwritersfestival.com/