It was just past midnight and the purple castle was bumping.

Those brave enough to walk past the looming, nearly three-metre-tall praying mantises guarding the front gate joined the crowd within to sway and step to the rhythms. Spinning out the tunes was a DJ on stage, perched just below a towering simulation of a medieval water wheel lit up with a projected flow of liquid superimposed with black-and-white video clips of the avant-garde variety.

In festival parlance, the place was a trip, and just one of many lovingly crafted set pieces for the eclectic oddball vibes of the Jai Thep Festival. Held this year at the very end of January at the Lanna Rock Garden near Chiang Mai, Thailand, the three-day event is now in its fifth year and, for the most part, is a place by hippies, for hippies – or anyone who shows up at the camp-in gathering with friendly intentions.

Back in the castle, a burst of familiar notes butted into tech house music to announce the opening theme of the Mario video games, an 8-bit chime immediately recognisable to the crowd. The DJ – Note Panayanggool, a 27-year-old Chiang Mai native better known as Notep – looked on with a smile through dark sunglasses as the gleeful dancers cheered, before she dropped the bass and sent everyone back to dancing.

Notep, who now commands a huge following in her native country – including more than 750,000 Instagram followers – got her start in music about a decade ago when she placed second on Thai reality TV talent competition The Star. In a Youtube video of one of those performances in 2011, she’s playing a ukulele and singing sweetly, a squeaky clean image that helped launch her into a pop contract after the show ended.

That lasted for about five years, a chapter of carefully manicured image and sound that grew to chafe against Notep’s musical ambition. When her record label contract expired, she broke out into a new period of electronica, performing as a duo with a friend under the name X0809.

With the new title came a new sound – and an image that shed her saccharine past. “We were just freaks,” she tells Southeast Asia Globe with a laugh, sitting on the edge of a children’s sandbox late into the night at Jai Thep. “We dressed up the weirdest that we could and sang these weird songs, but I loved it, it was so much fun.”

She looks more cool than freaky at the festival, where she’s wearing a shimmery blue baseball jacket that helps her stand out even in a crowd as funky as this one. She explains the period as X0809 eventually gave way to a solo run as a DJ and, most recently, a transition away from music to more visual and mixed-medium arts that embrace themes of mindfulness, meditation and, most recently, environmentalism.

That last point could open a new chapter for the budding advocate. She’s begun writing environmental messages into her work to share information with her audience in an easily digested package, and she’s working with like-minded friends to throw her public profile behind movements to clean up Thailand and its sea coast. She’s also started the work to reforest a piece of land she owns near Chiang Mai.

This bigger package of themes helped put her on a direct course to the eye-shaped gates of Jai Thep and its progressive ethos of environmentalism-cum-spiritualism.

The festival is part of a wider movement of socially conscious, ‘eco-raving’ music festivals cropping up in Thailand and the region. The most prominent of these is the pioneering Wonderfruit festival, the ‘Burning Man of Asia’ created by Thai duo Pranitan Phornprapha and Montonn Jira. First held in Pattaya in 2014 with an emphasis on sustainability and social responsibility, it’s a plastic free festival with stages constructed from biodegradable materials like bamboo, rice and hemp branches.

Still, an inescapable question remains how environmentally friendly any festival can truly be when calculating the carbon footprint of transportation, both for acts and revellers. Festivals with global cache – especially ones that attract tens of thousands of guests – can stack up emissions to match, and that’s still leaving out the more local considerations of waste and electricity usage. Some musicians and others in the industry have started advocating seriously for more climate-friendly touring schedules and on-stage gimmicks, but the logistics of greening a mass event can be tricky, even for big names.

Experts calculated in 2016 that the UK festival circuit alone produced almost 19,800 tonnes of carbon emissions every year, a massive sum that didn’t even count the traveling tonnage of artists and attendees. Soft rock group Coldplay pledged in November to stop touring until they could go carbon-neutral and, with increasing anxiety about climate change, they might very well be the first of a trend.

Such concerns could dampen spirits in the festival-saturated West, but for now, the party is still going strong in Thailand. Jai Thep and other festivals in the country bank partly on the fact they’re bringing in a crowd heavy in locals, whether native-born or expat – a demographic that does help reduce the overall carbon footprint.

And like the larger Wonderfruit to the south, Jai Thep also holds big aspirations of minimising its environmental impact, an ethos imprinted on the culture of the place.

Organisers signed on to the Festival Vision: 2025 pledge, a movement within the industry to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50% while working toward other sustainability goals. To that effect, Jai Thep festival staff and attendees also eschew single-use-plastic, meaning festival-goers at the Lanna rocks are now seldom seen without metal cups and bottles slapped with a psychedelic sticker. In a bigger sense, and in true camping spirit, guests there are also expected to pack out everything they bring in – theoretically eliminating much of the immediate impact on the popular recreation area.

The festival’s preference to march to the beat of its own upcycled-material-drum can take on other unexpected forms. Just off the mainstream, it’s easy enough to find people dancing, juggling or even deliriously laughing themselves into some kind of transcendence.

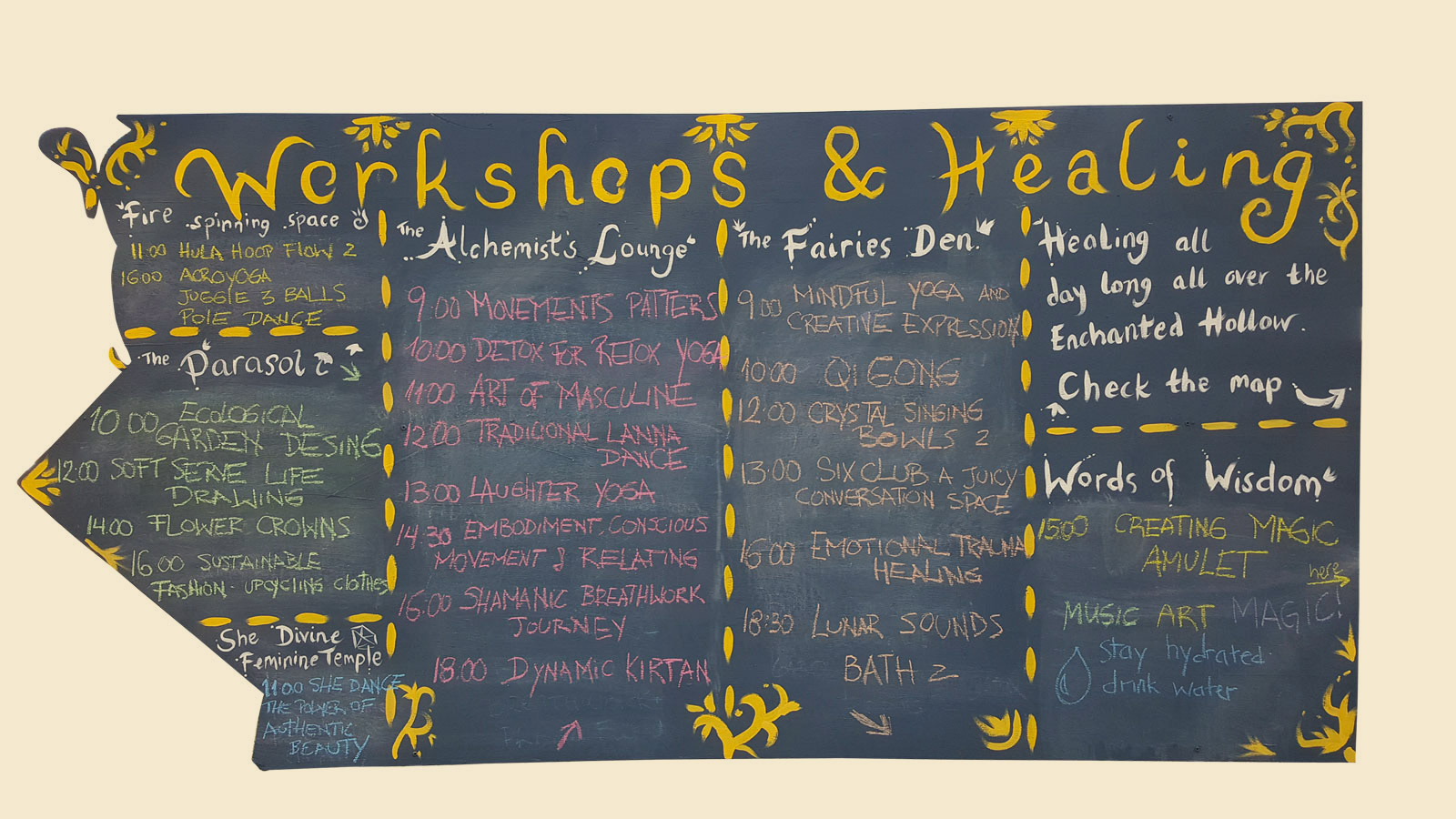

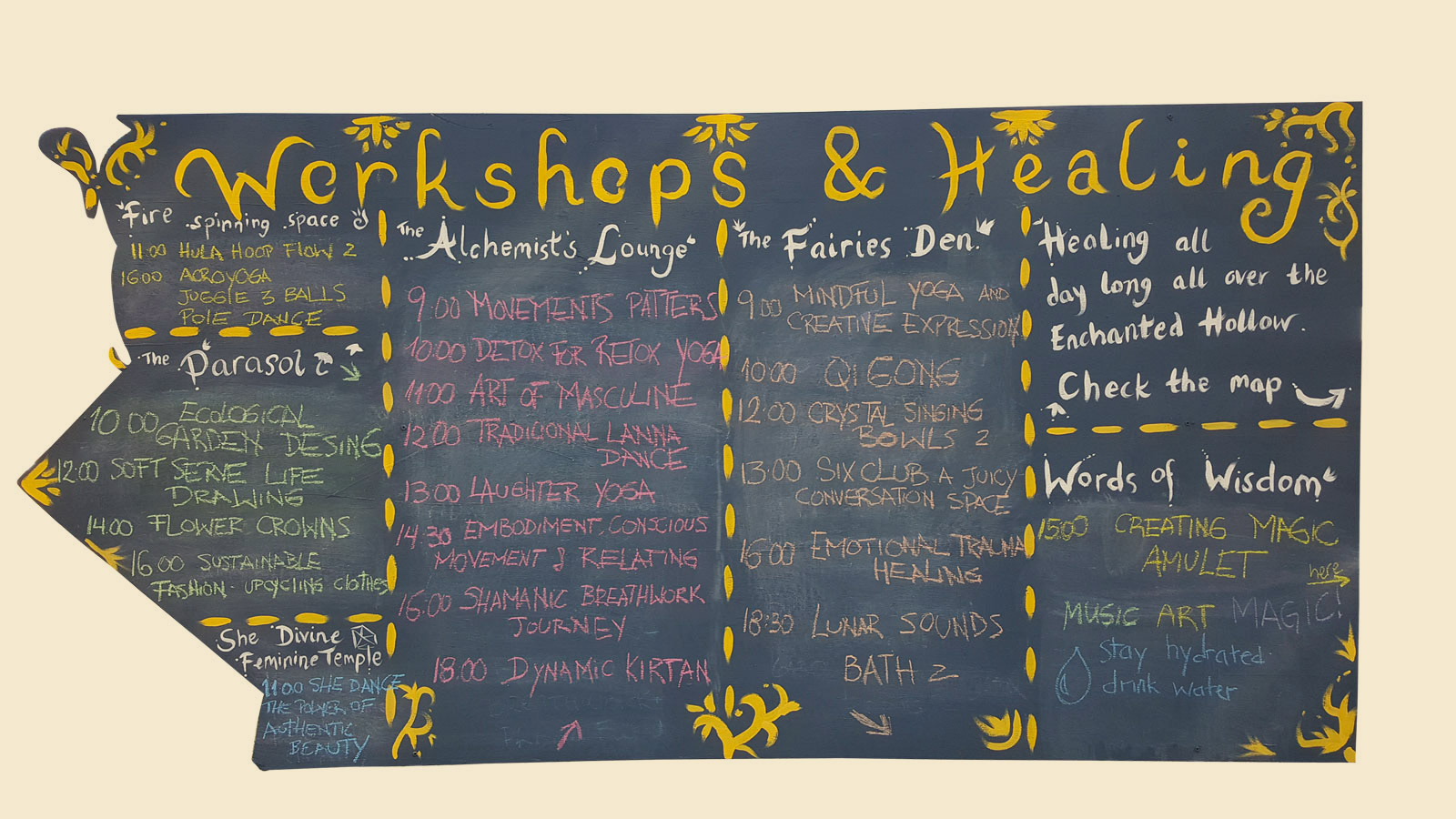

Saffiya Arnous helped facilitate that last one in a workshop devoted to Laughter Yoga, a practice developed by an Indian physician Madan Kataria that, in its very simplest form, involves a group of people laughing with each other for an extended period.

It’s a playful medium, and Arnous leaned fully into the spirit – she showed up to the workshop in full unicorn attire, from her pink-and-white unicorn leggings to the horn on her headband. Under her tutelage, the group worked through various games and exercises designed with the sole purpose of laughing hilariously with one another, first as a voluntary act and then, inevitably, in genuine, spontaneous bursts.

Arnous said she learned the practice in Chiang Mai during her five years of living here as an expat. Now back in her native France, she came back to Thailand specifically for Jai Thep and the friends the event draws together.

One such friend, a Roman-monikered American named Marcus Aurelius Higgs, described the event as a time when the “artist collective comes together” in an organic way.

“It’s not a commercialised thing,” Higgs said. “It’s very much by the people, for the people.”

Both Arnous and Higgs have attended the event since the start. Though it’s gotten bigger with each year and perhaps shed some of its founding do-it-yourself look, they both say it’s maintained its feel as an event that both draws from an existing community and builds its own during the three-day run.

This aspect of the festival draws in people from all over who happen to cross paths with Jai Thep.

Rocky, a burly character covered in tattoos, was one of them. A builder from the US who cavorted and danced his way through the festival in tiny shorts and a Western-style vest and hat, said he’d come across the festival a few years earlier and now helps to construct its fanciful stages and hang-outs. To that effect, Rocky said the nearest thing he’d seen to Jai Thep in spirit is the famed Burning Man festival in Nevada’s Black Rock Desert.

That mass counter-cultural event births each year a temporary settlement known as Black Rock City in the depths of the desert, a bloom of some 67,000 people who throw together an artists’ town for a week of uninhibited self-expression.

Though the spirit may ring familiar, the scale at Jai Thep remains small enough for old festival friends to run into each other with every step, a sentiment shared by one enthusiast who’d come in from the UK after a year away.

“It’s like a festival made just for me,” the reveller said, greeting friends by a stall that sold mulled, hot cider. It was night by then and temperatures had fallen to see-your-breath-levels, leading the guy to extol the multi-purpose values of his shawl, before switching to an emotional reflection on the tight-knit camaraderie of the festival. “It feels like the world gave this to me as a gift, like ‘Oh hi there, here’s something nice for you!’”

Beyond one man swept up in the feeling of a moment, ideas of interaction between individuals and the world are also streaked throughout a gathering like Jai Thep.

The festival as a whole has no religious affiliations of any kind, but there’s a definite spirituality to much of what’s happening here. Hippy subcultures have long favoured a blend of influences from East and West and, with many performers and attendees arriving from Buddhist Thailand or elsewhere in Southeast Asia, there’s a lot of first-hand experience with the meditative arts.

Even in the pulse of electronic music, Notep has found ways to connect art and mind beyond that of passive listening. She’s a big enough fan of so-called ‘sober raving’ to the point where she’s started her own movement “High On Your Own Supply” – a social-media-backed series of substance-free dance parties.

Ironically, the move comes at a time when Notep is transitioning away from seeing herself as a musician.

Last year, Notep began immersing herself in visual art, creating installations and performance pieces rooted in spiritual themes. The art was fed by a diet of research in forms of meditation and homeopathic, spiritual healing methods such as reiki, which purports to use channeled energy to affect the body.

“It has changed my life,” Notep said. “I’m more grounded, more Zen, to the point where people around me have said I seem calmer.”

Like the various yogis also in attendance at Jai Thep, Notep’s work also maintains steady focus on the subjects of breath and breathing. She’s experimented with the concept in her music and, in an installation piece, constructed a machine that responded to her breath to drag a large paint brush across canvas.

The topic even fits into her seemingly unrelated hobby of scuba and free-diving, which regularly takes her to the coral reefs of Thailand’s coastal islands. For an autonomous activity that literally requires no thought to perform, breathing can be deceptively hard, a discovery a Globe reporter made while sitting in on a yoga session intended to detoxify the mind and body through mindful breath.

Notep had some reassuring words on that.

“Everybody sucks at breathing, because we’re human and our minds go crazy all the time,” she said.

Part of her own period of self-exploration has included a dive into the meditative arts such as vipassana, a meditation style derived from Indian Buddhism. Notep herself was raised Buddhist and, while she doesn’t typically use her art to reflect on explicitly religious themes, she says the meditative elements of her work directly tie into its more abstract concepts.

“My dad is a Buddhist and he loves my work because he can relate to it so much,” she said. “Since he’s been coming to my shows, he’s been meditating again.”

So as the music in the purple castle slowly fades to mute and the three-day bender draws to a close, music-weary party-goers, ears ringing, slowly depart the area around Lanna rocks.

Their presence, in theory, will be undetectable in a few days time, as this quiet oasis returns to its momentarily interrupted resting state of tranquility.