Kao Kalia Yang was born in Thailand’s Ban Vinai Refugee Camp: a gift, her grandmother told her, in a time when her family did not dare to dream of presents.

Yang’s family arrived at the refugee camp 11 months before her birth in December 1980. The family had lived for five years hiding in the jungles of Laos from a genocidal regime intent on exterminating Hmong, a stateless ethnic group, ‘to the last root.’ When it became impossible to stay in Laos any longer, her family made the dangerous crossing of the Mekong River into Thailand.

Between 1975 and 1997, approximately 138,000 Hmong made a similar journey. Many who did not know how to swim did not make it to the other side. Yang’s father pulled her grandmother, mother and older sister across the raging waters tied together with bamboo.

Nine years later, Yang would listen to her father, Bee Yang, perform Kwv Txhiaj – traditional Hmong song poetry – under the bright fluorescent lights of a Minnesota civic center.

At the Hmong New Year’s celebration, her father sang to a rapt audience: “Lost are the ones who run through jungles without shoes, the young screaming for their elders to run faster, a giant moon on the other side of a river, the glittering water a mirror for what will come,” she recalled in The Song Poet: A Memoir of My Father.

Like her father, Yang has the skill of storytelling. Through memoirs, essays, children’s books and public speaking, she shares stories that often go undocumented about the Hmong, refugees and often unwritten topics.

The written Hmong language was destroyed by Chinese forces centuries ago. It wasn’t until 1950 when a French missionary translated the Bible into Hmong that the script reappeared. Now, Yang brings the oral history into the written form.

“My dad is a beautiful song poet,” she said in an early morning Zoom call from her home in Minnesota. “This ability to express the things that make his heart heavy, the things that lift the heart high… I’m following in the tradition of my dad and the great storytellers of my people but I’m working in an entirely new medium for my community.”

Yang’s parents were married in a clearing hidden in the jungle of Laos. The ceremony was muted. Sitting quietly, the couple listened carefully to the elders and for the sound of guns. “Everyone had heard the whispers,” Yang wrote in The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir. “A group of ten thousand North Vietnamese soldiers had entered from Vietnam to help the Pathet Lao soldiers capture the remaining Hmong.”

Laos was immersed in a civil war from 1959 to 1975 between the communist Pathet Lao and the Royal Lao Government. In the early 1960s, the US Central Intelligence Agency began recruiting Hmong people in Laos in an effort often referred to as the Secret War.

With the Pathet Lao allied with the Viet Cong, US military leaders saw the country as a threat during the Vietnam War and dropped more than 2 million tons (1.8 million metric tonnes) of cluster bombs on Laos between 1964 and 1973. In The Latehomecomer, Yang wrote of how “jagged pieces of broken mountain” rained down on her family and the “earth blew up in their faces.” The country is the most heavily bombed nation in the world.

US forces withdrew from Laos in 1973, leaving many Hmong behind among the Pathet Lao, which sought to rid all Hmong from the country. For those who surrendered to the government, there was death or reeducation camps. Many, like Yang’s family, headed deep into the jungle where they lived, evading those set on destroying them.

One morning, while Yang’s mother was boiling yams over a small fire, their camp was ambushed. After a months-long separation, the Yang family reunited and headed to the bank of the Mekong with a torrent of monsoon rains pouring down on them. By 20 May 1979, they arrived on Thai soil. They lay on the ground, wet and shivering, as soldiers firing guns were still visible on the other side of the river. Although scarred, they survived.

Yang’s first memories are in Ban Vinai Refugee Camp in northeastern Thailand. She remembers her mother, Chue Moua, instructing her that she could only play within an area stretching as far as her mother’s sarong. Holding the end of her mother’s cloth in one little fist, she’d play in the orange dirt with the other. It was only as an adult she realised the river of her childhood was nothing more than a sewage canal.

Approximately 45,000 people were crammed into the 400-acre (162-hectare) camp surrounded by cement walls and guarded by Thai soldiers. Thailand received a flood of refugees during the Indochina wars. By the time Yang’s family reached Ban Vinai, Thai authorities had adopted a program called “humane deterrence,” aimed at discouraging more refugees from seeking asylum in Thailand. As such, Hmong received food rations only three times per week, often consisting of dried fish and rice that smelled of “mold and dark places,” Yang wrote in The Latehomecomer.

Hmong were not allowed to leave the camp. When they did, many were beaten, raped or killed. Death in the camps was a regular occurrence. In a PBS documentary, a former camp occupant said that during his time in Ban Vinai there was “not one day where we didn’t carry the dead to be buried.”

Yang can’t forget the deaths. Traditional Hmong drums played the sound of a beating heart every time someone died. Yang would run crying to her family, making them promise her they’d live forever.

Although life was hard, Yang was surrounded by people who loved her: parents, an older sister, a grandmother, aunts, uncles and cousins. They treated her with care and buoyed her spirit with stories, she said.

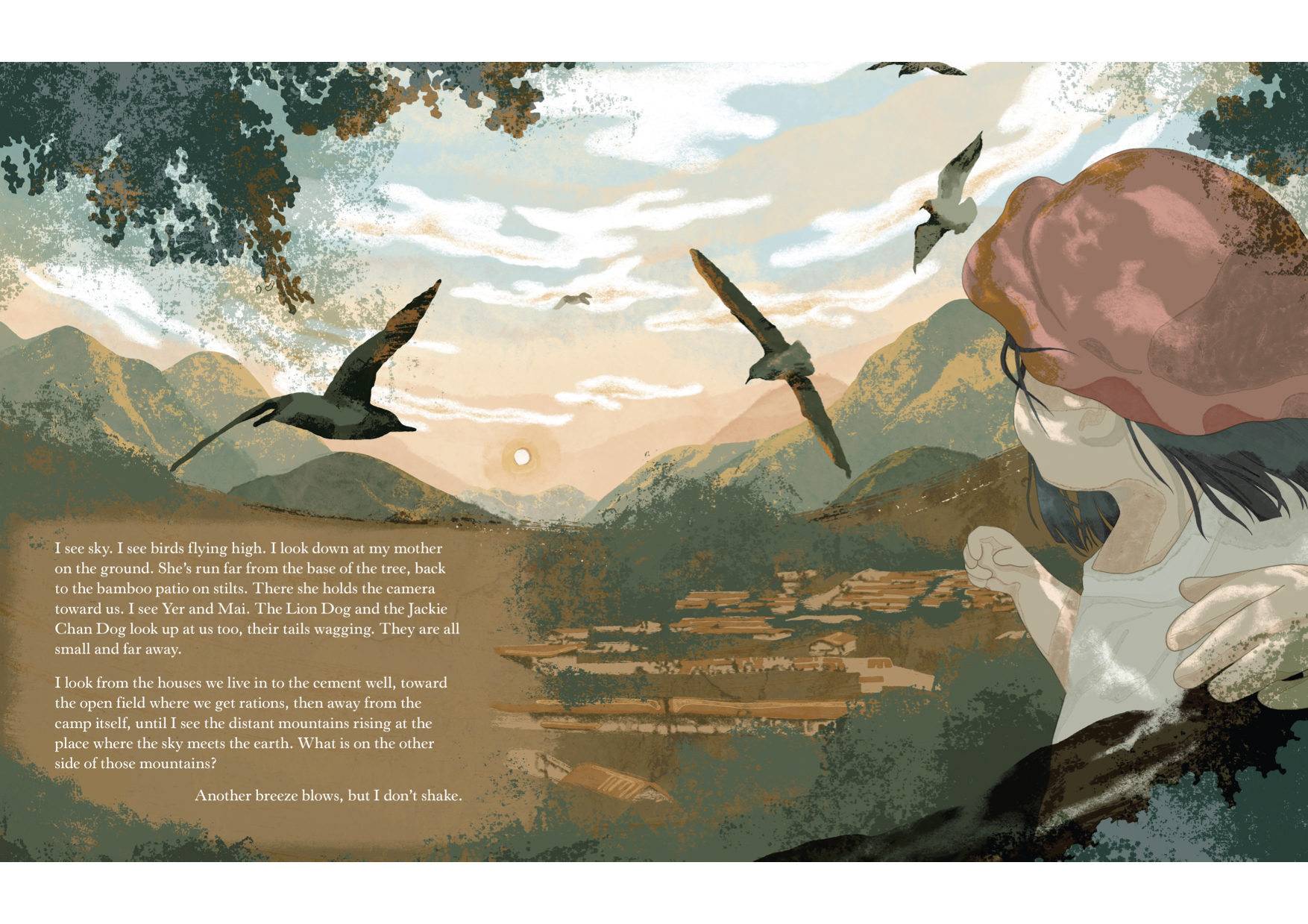

Her most recent children’s book, From the Tops of the Trees, recounts her time chasing chickens and playing with dogs amongst her cousins in the camp. One day, she asked her father if all of the world was a refugee camp. To show her life beyond the confines, he carried his daughter to the top of the tallest tree to look at the mountains in the distance.

Actions like these, and the “gift” of the words of her elders, imbued her life with possibilities, she said.

“Ban Vinai Refugee Camp was the place where I learned how to hold stories close,” she said. “It’s a place that was full of brutality but also full of the innocence of childhood memories.”

Yang was 6 years old when they left Ban Vinai Refugee Camp. But it was back in Thailand where the possibility of a writer’s life was born.

Before she returned to Thailand in her self-proclaimed “journey into Hmongness,” the Yang family had spent over a decade in the US, settling first in the McDonough Housing Project in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Yang felt the pain of seeing her parents become vulnerable in their adopted country: hearing her father’s voice, powerful in Hmong, faltering in English and her mother’s beauty becoming meaningless in her factory job. While her parents worked overnight shifts at a manufacturing plant, Yang and her older sister looked after their siblings born in America.

“Both my mom and dad are kind of hard of hearing now because it was so loud in the factories. They both have carpal tunnel in their hands now,” she said, raising her palms to the computer screen. “My mom and dad didn’t find an America that was understanding… I’ve seen what America has done to them.”

Education was the route to a better future but Yang was lost. When she heard her mother struggle for words in English, she decided not to speak the language. What was once the young girl’s act of rebellion grew into a silence inside her.

Although gifted in literature and dedicated to her studies, her teachers remarked on her difficulty speaking. She would nod and whisper, now describing herself as a selective mute during those years. She was nonetheless accepted into distinguished Carleton College, where a racial incident would drive her to search for herself in Thailand.

Walking along the river near her university in southern Minnesota, a car pulled up to her. Thinking they were lost, she walked to the window. The two men inside flung trash at Yang and yelled racial slurs.

“They threw the remains of McDonald’s at me, ice cubes, ketchup, and they called me all kinds of things and they both yelled, ‘Go home,'” she said. “I came back with like this broken heart and I thought in my head that I was going to go home.”

Although it wasn’t the first time she’d encountered racism in the US, it was a particularly isolating incident, she said. At Carleton, she was surrounded by a primarily wealthy and white student body and didn’t feel understood. The experience left her with a desire to return to the first place she remembered “being alive.” She wanted to go back to Ban Vinai Refugee Camp.

I found a source of strength that I didn’t know I had

Kao Kalia Yang

She headed to Thailand through a study abroad program focusing on global development among the rural poor. After arriving, Yang found the refugee camp of her birth had turned into a rubber plantation. Still, the place exists in her heart, in the hearts of other children and the families who survived the camp, she said.

Turning 21 years old in Thailand, she developed the idea that “memories had work to do in the world,” which included the perception of herself as a writer with a responsibility to the greater world without a need to be from one country alone.

“I found a source of strength that I didn’t know I had,” she said. “I came back much more stubborn about holding my memories safe but also that I’m American.”

In a small yearbook for the study program, her cohort predicted one day Yang would become a novelist. “The idea of writing actually, as a possibility, was born in Thailand,” she said.

With strength and responsibility established in Thailand, Yang now writes for people deleted from history, for those afraid of being forgotten, holds space for grief and gives lessons for survival.

This year, when she saw pictures of Afghans clinging onto the sides of planes after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, she was inspired to publish a collection of letters to refugee children. “I wanted to reach out in the way that I could, through words, to communicate all of that yearning, all of the hunger, all of that fear, all of the loneliness,” she said. “Dear refugee child…,” she begins the five essays in Al Jazeera, guiding the reader through childhood to adulthood in a new country.

Like the medicine her late shaman grandmother Youa Lee would concoct, Yang’s writing provides a balm for those in need. Yang doesn’t write stories the world wants, she writes stories the world needs, she explained.

“When I was a kid, to my knowledge, there were no refugee writers writing to me, thinking about me,” she said. “For me, there’s no question that the books that I write are essential… Every single thing I do is a love letter to someone somewhere.”