When did you become interested in photography?

It really came out while I was going to university. Given the political situation in France at the time, it was a good time to go to demonstrations and play with the camera. My first trip to Cambodia was in the summer holidays in 1973. I worked the night shift at a gas station for two months to pay for a ticket. It was a trip to somehow get used to life in a war zone. I had to go back to France but I planned to come back here [Cambodia] in 1975. By the time I had got money together it was the first week of March in 1975.

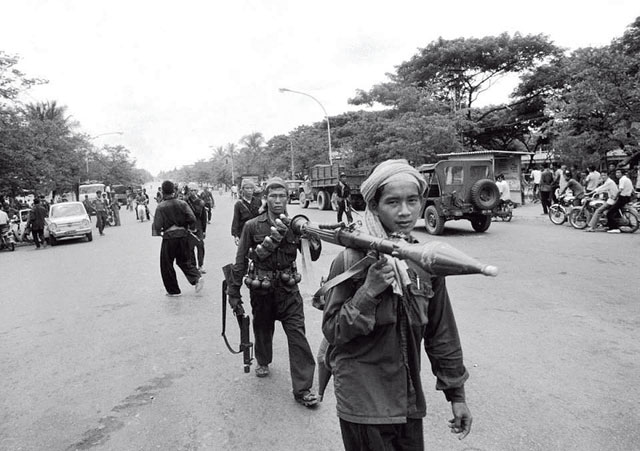

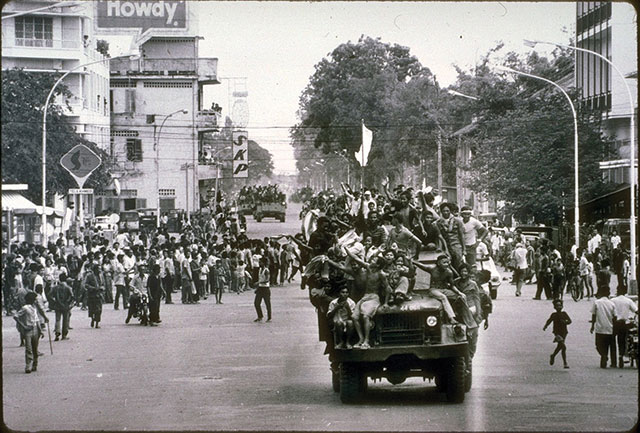

What was the atmosphere like during the fall of Phnom Penh?

Everything was slowly building to that. We didn’t know that they would evacuate and that’s the first thing: Nobody around me, to my knowledge, anticipated that situation. We know now that they said the city would be bombed and they wanted everybody out. It was a big plan, but we didn’t have a clue. That is the amazing thing that most people don’t consider now: When it happened, it was calm. There were probably a few [who questioned it] but most people just followed the orders. It’s human nature as well. If you say something, people will do it. It’s amazing.

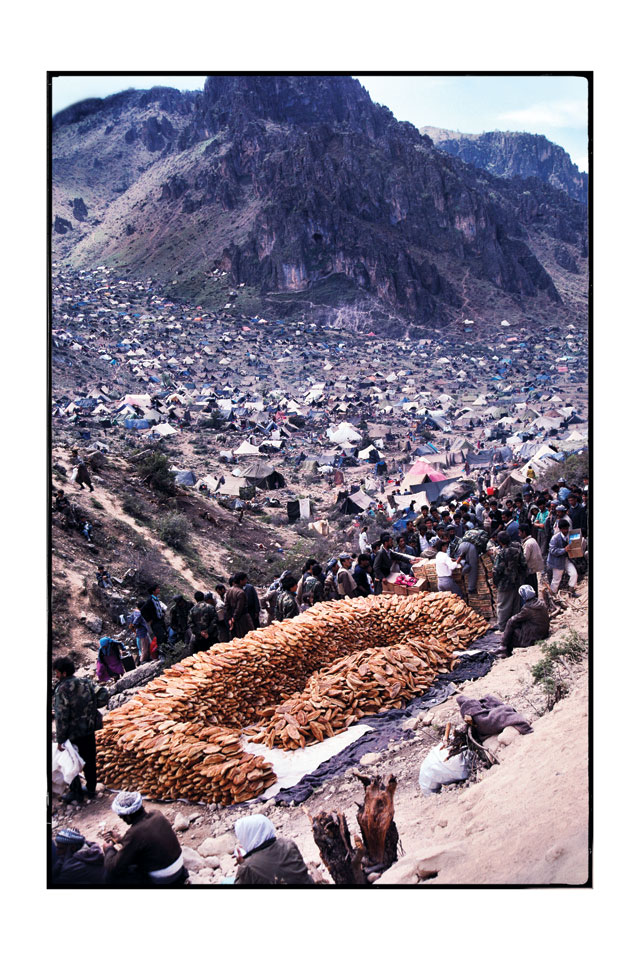

You‘ve covered conflict in numerous places around the world. Where else have you been?

What is a conflict? How do you define that? That’s the first thing. I did a lot of work for Time magazine – that had been my mainstay since the early ‘80s. I’ve been to Afghanistan a few times and I covered Lebanon extensively, from the invasion in 1982 up until 1985. I’ve done a few trips to El Salvador and Nicaragua. I covered the Philippines throughout the mid-1980s; I did quite a few trips with groups in the jungle, the kind of trips where you regret what you’re doing – the Philippines has some pretty harsh terrain.

So were there times when you wished you’d chosen a more sedate career path?

It was very, very hard and very uncomfortable. I was fit but sometimes by 3pm I couldn’t move any more, and many times I’d think: ‘Why did I come here? It was stupid.’ Yes, I cursed my decision often. But it emboldens you in a way too. You build up resistance and accept your fate. You put yourself into a situation where you are in a very unfamiliar area with unfamiliar people and you have got to trust them.

Was there ever a time when you were scared?

Scared is not the word, but in Lebanon two of my friends had been kidnapped so a group of us decided to go do a story on that area. It was an area that was occupied by Hezbollah and they caught us. They came around with their Kalashnikovs and took us to some place where we were separated, had hoods put over our heads and interrogated. We were in the mouth of the wolf but I remember I was not scared. Looking back, that’s one time you should be scared. But when it is happening, you aren’t thinking about that. For me, if you’re scared, you’re incapacitated. But when you’re in a situation like this, you can’t be incapacitated – you have to keep all your senses to try to manage the situation.

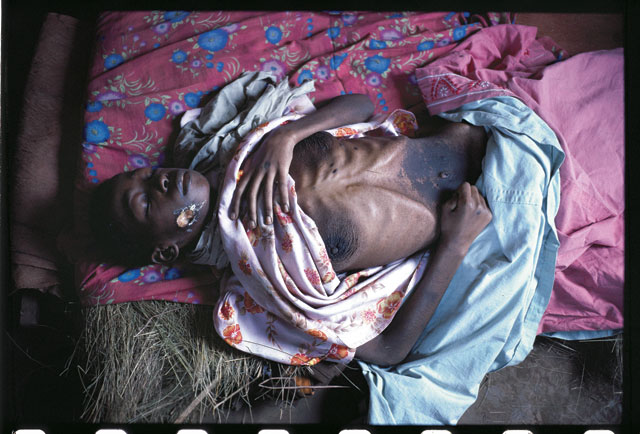

Despite the adventures, you eventually became quite jaded by the news industry.

They were giving more coverage and space to show business than to the real stuff, and I was disappointed about that for sure. Also, I’d been used to not having to fight to get work. I didn’t exactly turn my back on the news business but we weren’t getting long assignments any more and everything was getting chopped down. I felt they weren’t giving attention to the news we were working on. I worked mostly with US magazines such as Time and Newsweek and I noticed a ‘news tiredness’. Now, it’s very obvious we live in an era where the news is not news.

Around that time Hollywood came calling…

It was exciting. I was still in my mid-30s, it was a totally new experience and I was getting paid three times what I was in news. It’s nice to work with people who appreciate your work, rather than taking risks and giving it to people who don’t give a damn. It’s a real challenge because there are a lot of things happening on a movie set. You just have one set of eyes and you have to see it from many angles. And you have to be quiet, you have to learn that. It’s like in a conflict: you have to hide yourself away. Of course, my previous experience helped me and that’s why I was hired initially to work on war movies, starting with The Killing Fields.

What makes a good photojournalist?

One of the very important elements, I believe, is that photojournalists should know the situation they’re covering. I’ve always found it most disturbing to see people in places and they have no clue what is going on! As a photojournalist you are also a journalist so you need to have the knowledge, the background of the situation and all these things. You have to try to put meaning in the images.

You have pulled the flak jacket back on in recent years to cover the riots in Bangkok. Why?

I never wore a flak jacket, never. Nor a helmet. That is really something that started in the ’90s. Anyway, I covered it because it was happening in my backyard, and also because it’s always interesting to test yourself in dangerous situations. I covered the big trouble in Bangkok in 2010. That was my return to the frontline. I haven’t given up on trying to understand the world. I was an old-timer, but I was pretty confident I could handle it. While I was shooting, something occurred to me: Nowadays it’s so much easier to shoot everything. I shot the fall of Phnom Penh with six rolls of film! I was very careful every time I pressed the shutter, hoping it was for some good reason. It’s like war in a way: In Afghanistan you see soldiers going through ammunition almost endlessly, but then you think of a guy in World War I. When they took a shot they had to be damned sure they were aiming at something.