In this age of population explosion, space is of the essence. Asia’s population quadrupled in the 20th Century and it is also experiencing a far greater urbanisation rate than the rest of the world. In 1950, only 17%, or 232 million people, lived in urban areas. Come 2030, this number is expected to reach 2.7 billion, or 55% of Asia’s total population, according to the Institute for Sustainable Communities.

It is expected that by 2020, two-thirds of the entire urban Asean population will live in five ‘Mega-Urban Regions’ (MURs): the Bangkok-centred MUR, the Kuala Lumpur-Klang MUR (the capital, its suburbs and adjoining towns in the state of Selangor), the Singapore Triangle (Singapore, the state of Johor in Malaysia and the provinces of Riau and West Sumatra in Indonesia), the Java MUR and the Manila MUR, with a total population of 176 million.

Considering such staggering rates of urbanisation, close attention is being paid to how we live and interact in urban environments. Significant demographic, socio-cultural, environmental and political changes occur as urbanisation increases, and these must be addressed as urban societies move forward.

Take a look at some of the projects aiming to respond to the region’s rapid urbanisation and create cities that are more functional, sustainable and supportive.

Big things, small packages

Urban densification suggests that the most socially and environmentally sustainable way to build and live today – and into the future – is to make our spaces more compact and closer together, while also preserving communities and public spaces.

The smaller the space, the less energy it takes to heat or cool and the fewer resources it takes to construct, which, in turn, saves money and lessens environmental impact.

Measuring 97 square-metres, the Living in the City housing unit prototype was created by the Bangkok-based design outfit Apostrophy’s. With space constraints, accessibility and sustainability at the core of the design, the unit is comprised of two main floors, two mezzanines and a green area.

“When urban society consumes natural resources that contribute to pollution, people begin to realise that they must use natural resources efficiently, as well as green space and sustainable design solutions,” says Nattarat Thiankhao, Apostrophy’s exhibition designer and project coordinator. “The Living in the City project originated through many design concepts – using renewable energy, reducing energy use and utilising durable and recyclable materials. These innovations have been used to allow nature to be part of better urban living.”

The first floor of the unit has been designed with the disabled and elderly in mind – something not often addressed in Southeast Asia, despite the region’s ageing population and the relatively high incidence of physical disability in places such as Cambodia. The unit is wheelchair-friendly and has built-in ramps for easy access. Multi-purpose furniture, plenty of storage and seating, and the option to grow small plants and herbs on the green wall make the Living in the City concept tailor-made for these times of economic uncertainty.

Rising to the challenge

More than three billion people across the globe rely on rice as their major food source, which creates a massive demand for not only the grain itself, but for the land on which to grow it.

Uniform rice paddies are synonymous with many people’s idea of the countryside in places such as Vietnam, but when the financial and environmental cost of rural farming is too high to sustain, urban agriculture solutions come to the fore.

Enter architecture student Jin Ho Kim’s proposition for vertical rice farms, tailored to be successful in urban centres such as Manila. The Philippines is one of many countries that struggle to maintain food production while being able to devote land to housing and other industries.

The concept of vertical farming is not breaking new ground, but it is yet to be realised to any great effect. Ecologist Dickson Despommier, a professor at Columbia University, introduced his theories on the vertical farm back in 1999. He estimated that to feed rapidly expanding populations, “the world will need one billion more hectares of arable land by 2050 – roughly the area of Brazil and far more land than will be available”.

Despommier claimed that one vertical farm could grow hundreds of acres worth of crops in a few city blocks. “If successfully implemented, [vertical farms] offer the promise of urban renewal, sustainable production of a safe and varied food supply (year-round crop production), and the eventual repair of ecosystems that have been sacrificed for horizontal farming,” he wrote in his book The Vertical Farm.

Dead space brought to life

In Kampung Pakuncen, a small village in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, the locals needed a space to hold their daily meetings but lacked the money and resources to make it happen.

Some women from the local community decided to take action and joined a citywide network of 31 riverside communities known as the Kalijawi collective. The group helped the women to establish a savings pool and after four months, they had raised a total of $2,500.

With this money, they were able to enlist Southeast Asia’s most iconic material to get the job done – bamboo. Community architect Andrea Fitrianto designed the space and teamed up with engineer Jasri Mulia and the NGO Asian Coalition for Housing Rights to have it built. What was born was the Black Bamboo Community Centre. Made from the fast-growing ‘wonder grass’ known as Gigantochloa atroviolacea, the structure also made use of dead space: elevated on stilts in a narrow area between two existing buildings and above

a drainage channel.

“In urban areas, poor communities are used to sharing limited resources among themselves and they are very smart at overcoming space limitations,” says Fitrianto. “The location of the centre was chosen by the community, while the architects adapted to the context and constraints.”

The sturdy, airy structure was built over two months with the help of local villagers as well as the architectural not-for-profit group Architects of Arkomjogja, which Fitrianto was a part of. The centre is a fine lesson in weather-appropriate architecture, too – cool and breezy in hot weather and built on an elevation to protect it from flooding.

According to Architecture in Development, an online user-generated platform for shared learning among groups such as Architects of Arkomjoga, the Black Bamboo Community Centre exemplifies “a bottom-up approach, inclusiveness and participation in urban development”.

A tiny tipple

Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, is swiftly becoming something of a foodie’s paradise. Alongside the continued openings of high-end restaurants is a steady stream of small, skilfully designed bars and nightlife spots.

One particular alley, known as Street 240½, is home to a number of these pint-sized drinking holes. One of the most recent additions to the quaint thoroughfare is The Alley Bar, designed by Re-Edge Architects and Design.

“Small spaces make people think about the details of their requirements and allow creativity to take off, compared to larger spaces,” says Hun Chansan, Re-Edge’s director of design. “Small spaces and neighbourhood spaces have a bigger impact on cities and their people as they are closer to home, compared to larger spaces where people may not feel a deep sense of belonging.”

The alley is not wide enough to accommodate cars, allowing peace and quiet for pedestrians perusing the lane’s cafés and boutiques. Street 240½ encourages face-to-face encounters, in stark contrast to some of the city’s more established and commercial boulevards. One cannot simply roll up to The Alley Bar in an SUV, windows blacked out, and flick car keys to a waiting security guard before scurrying inside.

It’s not just Southeast Asia that is turning up solutions for urbanisation. Around the globe, the ideas are as diverse as the countries they’re created in

Post-community

Accelerating densification means that cemeteries are struggling to maintain their relevance as public urban spaces. This project, by Marta Piaseczynska and Rangel Karaivanov in Austria, aims to create a cemetery that functions as an interface between the living and the deceased. Calling out the name of a deceased loved one results in their urn being transported to the visitor, with the other capsules moving Tetris-style around it to make way.

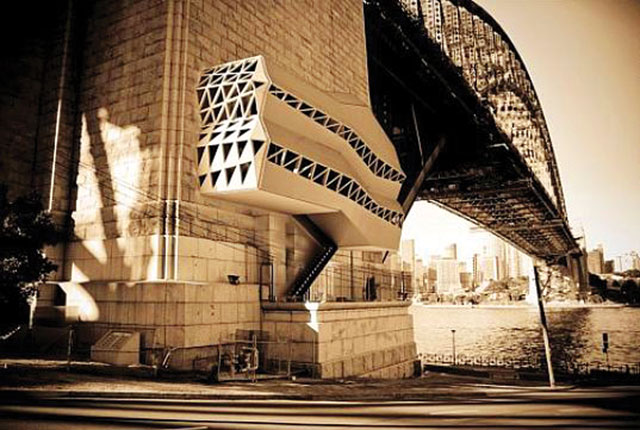

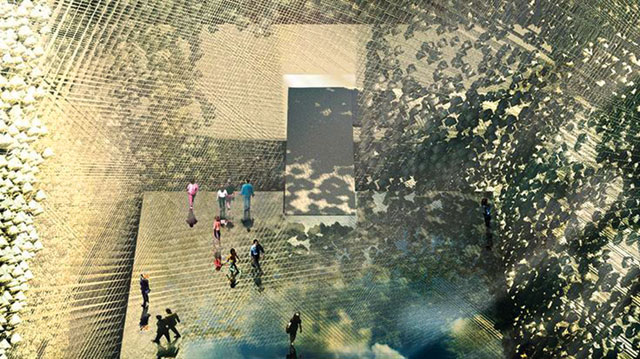

Parasite prefab

Designed to make use of idle space in urban landscapes, the Parasite Prefab by Australian firm Lara Calder Architects ‘grows’ on empty facades, rock faces and bridges. The actual footprint of the structure consists only of the stair landing (which is retractable) and the services duct. Inside are four floors, complete with bedrooms, bathrooms and a study, plus there is a roof terrace to enjoy the views from wherever the parasite has found a host.