SCROLL LEFT TO READ

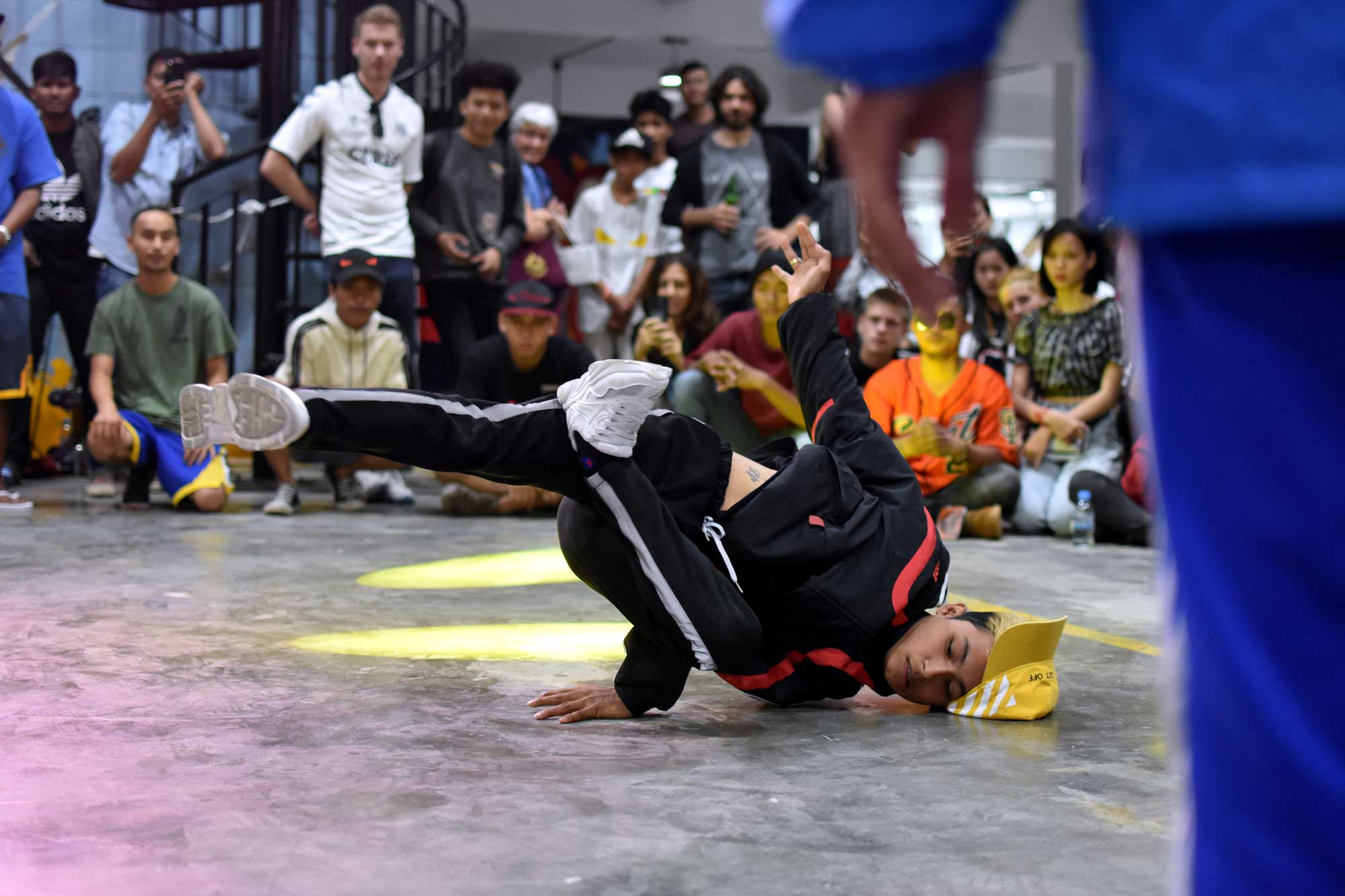

In a working class neighbourhood on the outskirts of town, breakbeat and hip-hop reverberate around a high-ceilinged hall in what was once a garment factory, now a mural-strewn art gallery and creative hub.

A DJ presides over proceedings spinning vinyl in his booth as, phones out, modish spectators groan and whoop as two b-boys battle before three inscrutable, expressionless judges.

There ain’t no losers here tonight, only winners.

“There ain’t no losers here tonight,” the MC says – his dialect and accent unmistakably southern Californian – as the judges gesture towards the same red-shirted breaker. “Only winners.”

An unremarkable scene across major US cities today, in the Cambodian capital Phnom Penh, this nascent breaking community is a bold display of youth culture less commonly seen in the Kingdom.

The event’s organiser, Cambodian-American Tuy ‘KK’ Sobil, says his work has ruffled feathers among the country’s traditionalists. His charity initiative Tiny Toones – which began in 2004 as a breakdancing school for street kids, but now provides free education to hundreds of impoverished children – trained up the majority, if not all, of the young Cambodians participating.

“At first it was hard. I was called a sell-out by the

Cambodian arts scene because I brought hip-hop. They’d say you’re making Cambodia look bad,” the heavily tattooed 42-year-old tells Southeast Asia Globe from the charity’s modest youth centre-cum-school.

“In another way my parents think I’m challenging Cambodian society because of how I look and how I represent myself.”

Four decades in the making

That a breaking scene exists at all in the country owes to a series of profound historical events and social forces four decades in the making.

When streams of black-clad Khmer Rouge fighters entered Phnom Penh on 17 April 1975, greeted by streets lined with cheering crowds relieved to see an end to half-a-decade of fighting with government forces, few could have guessed the scale of the tragedy that would unfold.

Between 1975 and 1979, Pol Pot’s ultra-Maoist regime would embark upon a genocidal programme of social reconstruction that would result in the murder of 1.7 to three million people – a quarter of the Cambodian population at the time.

In the midst of this violence, KK’s family were among the hundreds of thousands of Cambodians who sought safety in refugee camps on the Thai border, where he was born in 1977 – a “refugee baby” as he puts it.

His family were also among the approximately 149,000 Cambodian refugees granted asylum to the US between 1975 and 1994, where significant populations emerged in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and KK’s new home – “little Cambodia town” Long Beach, California.

But while the US represented refuge for many from the horrors of 1970s Cambodia, the asylum process brought with it hardships that persist to this day.

Little social support was afforded to the huge number of new arrivals, scarred by war and housed in insular communities in the unforgiving surroundings of the country’s poorest districts. As a result, many struggled to assimilate.

KK’s mother, a resident of the US for three decades, still speaks little English he says. Unsurprising then that his parents, like many emanating from his community, never truly understood their legal status as refugees in the US, resulting in their children never claiming citizenship as they were entitled.

“I blame the US, my parents were never taught the routes, there was no community place where they learned how to do this stuff [claiming citizenship]. They just took them from refugee camps and threw them in the projects,” he says.

It is in this context that Cambodian-American street gangs sprung up in the 1980s, populated by the second-generation of rudderless young men, straddling cultures while not truly belonging to either. The Tiny Rascal Gang is the most prominent among these, a 10,000-strong Cambodian-American street gang that emerged in Long Beach.

KK’s trajectory – from refugee child, to unanchored youth, and eventually gang member – is a dispiritingly common one among those in his community.

“I was part of a [breakdance] crew called Ground Force back in Long Beach. I started breakdancing when I was around eight. From breakdancing I went into tagging and graffiti, from graffiti I ended up joining a gang and getting locked up and going to jail.”

I was part of a [breakdance] crew called Ground Force back in Long Beach. I started breakdancing when I was around eight. From breakdancing I went into tagging and graffiti, from graffiti I ended up joining a gang and getting locked up and going to jail.

Between two worlds

It was in jail where the gravity of KK not holding US citizenship became fully apparent.

As a permanent resident, he was liable for deportation after his armed robbery conviction – an “aggravated felony” – under the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) signed into law in 1996. So despite having never set foot in his ancestral home, as well as having a son in California, once KK had served his sentence in 2004 he found himself among the 48 Cambodian-Americans deported back to the Kingdom that year in similar circumstances.

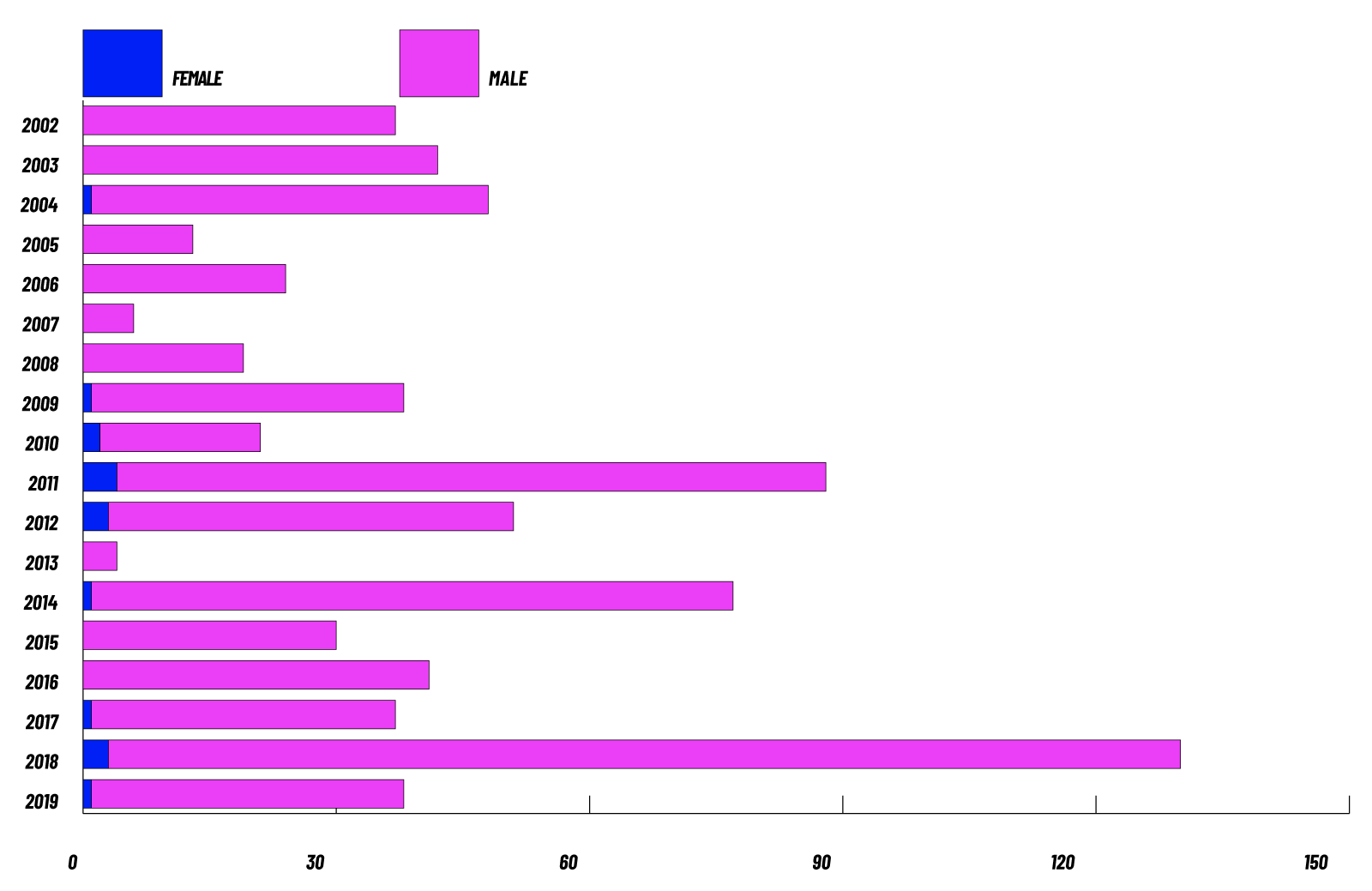

According to statistics provided to Southeast Asia Globe by the Khmer Vulnerability Aid Organisation, which helps deportees integrate into Cambodian society, there were 743 Cambodian-Americans deported back to the Kingdom between 2002-2019 – an average of 45 per year.

It’s a phenomenon that has only grown under the anti-immigrant drive of current US president Donald Trump.

“Two years ago, we were told by US authorities to prepare to receive 200 per year for the next five years,” said Bill Herod, an American development worker who has worked with Cambodian repatriates since 2002. “We believe the proposed dramatic increase in the deportation of Cambodian refugees is a result of the anti-immigrant policies of the current US administration.”

American in all but passport, these men have brought with them many aspects of the culture they have left behind, with breakdancing, graffiti and hip-hop examples of thriving scenes that have grown in Cambodia largely driven by deportees.

“There was no breakdancing here when I arrived [in 2004],” KK says.” Through Tiny Toones it’s grown a lot. Now you can find all types of dancing – poppin’, lockin’. We’ve helped close to 10,000 kids and it’s getting bigger and bigger [breakdancing and hip-hop in Cambodia].”

But just as breakdancing represents a element of KK’s former life that he’s introduced to his new home, he says that through Tiny Toones, the scene has also been instrumental in helping him “connect to my culture again”.

“The KK of before is long-gone. Now it’s a new KK who’s just trying to get along in the world and give back to the community,” he says. “My past is my past … I grew from it, now it’s my job to help kids not make the same mistakes I did.”

So back in the airy auditorium of that converted factory on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, KK sits embracing his young daughter as two breakers battle one another – the product of 15 years of personal growth and repentance spinning, poppin’ and lockin’ before him.

If you would like to learn more about Tiny Toones and donate to help sustain their invaluable work keeping at-risk Cambodian children off the streets, you can visit their website here.