Southeast Asia might struggle to sustain rapid economic expansion

with the world’s growth patterns beginning to transform

By Christian Vits

The lights are coming up on Southeast Asia’s last decade growth party. While global growth is gradually strengthening with brighter growth prospects in the US and Europe, emerging markets such as those in Asean face unaccustomed challenges. Times are changing.

“In contrast to the favourable external environment that existed before the [financial] crisis, during the next few years emerging markets will need to navigate through conditions that will be less conducive to growth,” the International Monetary Fund (IMF) said when presenting its World Economic Outlook in early April.

“On the one hand, emerging-markets growth will be supported by higher growth in advanced economies, on the other hand, the expected slowdown in China and somewhat tighter external financing conditions will weigh on emerging-market growth.”

The Washington-based organisation expects advanced economies such as European countries and the US to expand by 2.2% and 2.3% on average this year and next respectively, up from 1.3% in 2013. The figures are unchanged from previous estimates published in January.

By contrast, the fund lowered its overall growth expectation for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, the so-called Asean-5, by 0.2 percentage points to 4.9% this year. Next year, the region will expand by 5.4%, the IMF said.

Possibly most worrying for Southeast Asia is a more pronounced slowdown in China than currently anticipated. The gross domestic product (GDP) of the region’s giant neighbour may increase 7.5% this year and 7.3% in 2015, according to the IMF.

The expansion therefore comes close to the 7.2% minimum pace of growth needed to reach the target of creating ten million new jobs per year, according to China’s premier Li Keqiang.

Beijing has embarked on several ambitious structural reforms to reduce vulnerabilities that will impact key areas of the economy. Among the measures are state-owned enterprise reforms and an increase of prices or taxes for energy, water and other utilities, all potentially weighing on the country’s economic prospects.

Incentives for senior local officials to focus less on quantitative than qualitative growth targets, as well as efforts to tighten credit growth and measures to bring local government debt under control, may also have economic repercussions.

“The reform agenda is critical and well-designed. It has the potential to improve the quality of growth, make growth more inclusive, and ensure it is sustainable over the long term,” said Juzhong Zhuang, deputy chief economist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB). “But as changes roll out, growth could slow further before it stabilises or rises again.”

In fact, China accounted for more than a third of total global growth over the past five years – and for almost half of the emerging and developing economies’ growth. “China’s success is critical to the success of the global economy,” IMF managing director Christine Lagarde warned during a visit to China in March. To put it simply, the days of double-digit economic growth numbers in the Middle Kingdom seem to be over.

But it’s not only the speed of expansion that matters. “China will probably report close to 7% or higher growth [in coming years]. The issue is not the growth number but the reality on the ground,” said Manu Bhaskaran, founding director and CEO at Centennial Asia Advisors in Singapore.

The question is whether “the economy [will] be marked by financial or other stresses as the credit overhang and overinvestment of the past few years is rectified.”

Official figures put China’s total government debt at 30.3 trillion yuan ($4.89 trillion) in June 2013, 54% of last year’s GDP. Of this, local government debt amounted to 31% of GDP. Credit growth in Asean’s biggest trade partner continued to surge throughout 2013 at nearly twice the rate of GDP growth. Non-financial companies reportedly have debt equivalent to 120% of GDP, much more than in most major economies.

The size of China’s shadow banking sector – financial institutions that provide services similar to commercial banks outside or only partly within the traditional regulation – is also worth noting. It is estimated at about 60% of the country’s GDP – three times larger than at the end of 2008, but still relatively low compared to advanced economies, the United Overseas Bank (UOB) reported in a research paper.

“A near-term financial crisis is unlikely, but given recent rapid credit growth and growth of shadow banking, there could be continued news of credit problems among trusts or potential debt-servicing problems among local governments,” the IMF said.

“These could spark adverse financial market reactions both in China and globally.” Banks’ non-performing loans may amount to 9 trillion yuan ($1.4 trillion), Eugene Leow, an economist at DBS bank, estimated recently.

Still, there’s no reason to panic. Given the relatively low level of central government debt compared to more advanced economies and large foreign exchange reserves, China should have the tools to master financial tensions in case default risks materialise. “If it comes to the crunch [and] the banking system needs to be rescued, the central government appears to have sufficient flexibility and resources to come to the rescue, putting aside the issue of moral hazard,” UOB said in an email.

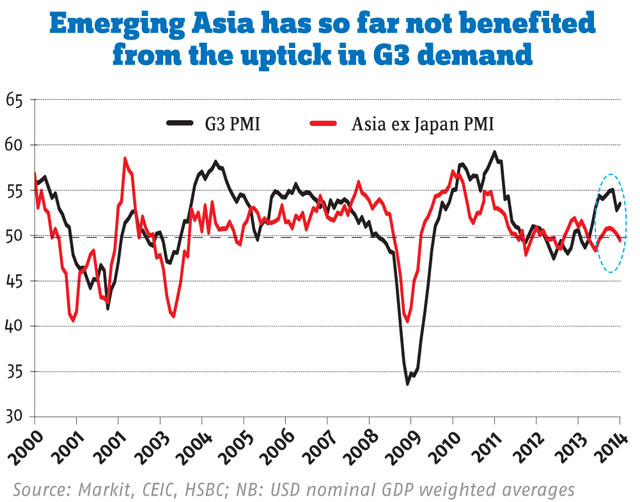

Certainly, export-reliant Asean member states will find some hope in the gradual recovery in Europe and the US. But even here, patterns are changing, according to Frederic Neumann, co-head of Asian economics research at HSBC in Hong Kong. “In the past few months, the purchasing managers’ indexes [which indicate future economic growth] in advanced markets have ticked up nicely, but, unlike previously, Emerging Asia hardly benefited. This is not just a blip. There’s something structural going on,” he stressed.

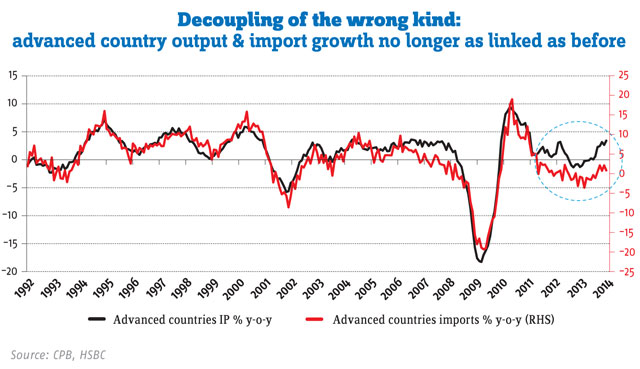

While industrial output and import growth in advanced countries have gone hand-in-hand over the past two decades, there has been a disconnection since about 2010, when accelerating production stopped triggering the traditional increase in imports.

According to Neumann, this reflects a slowdown in global trade, suggesting the composition in world GDP growth has shifted to less trade-intensive sectors. Another explanation could be that emerging markets, particularly in Asia, have lost competitiveness as the labour cost advantage narrows, prompting a relocation of production closer to home markets and resulting in a less vibrant export rebound in Asia.

Shipments of PCs and laptops, as well as other peripherals, remain under pressure, burdening Asean producers such as Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines and Singapore, which are more exposed to this sector, Neumann added. “Shipments to the EU have improved for most Asian economies, but the picture is more mixed for exports to the US and China,” he said. At the same time, Japan, Emerging Asia’s third-biggest market, looks set to throttle down in coming months as a recent the sales tax hike bites into consumer spending.

Last but not least, the tightening of monetary policy in the US might take its toll. In May last year, former Fed chief Ben Bernanke rattled financial markets when he started to talk about cutting back monetary policy stimulus, the so-called tapering. Speculation about the tightening’s timing lead to global portfolio shifts towards U-S assets whose yields nearly doubled, causing stock market indices to plummet and depreciating currencies in Asean member states.

The issue came back on the table in March when Fed chairwoman Janet Yellen indicated that the central bank may decide on an interest-rate hike as early as spring next year. While the bank previously always stressed it would take “considerable time” after ending its bond purchase programme before pushing borrowing costs higher, Yellen said in her first press conference that the timeframe for raising interest rates could be “around six months” after the stimulus is withdrawn.

The era of abundant, cheap money is definitely nearing an end. “We are sure that the taper will continue through the rest of the year, interest rates will rise, [capital] flows will be more discriminating, and Asian [currencies] will be under pressure, at least for a while,” said Taimur Baig, chief economist at Deutsche Bank in Hong Kong.

“One can debate about the pace, magnitude and timing of taper and rates normalisation […], but the fact of the matter is that rates have only one way to go, barring some major negative shock to global growth or sentiments.”

Debt levels in Southeast Asia, especially household debt, have steadily increased in recent years. Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand for instance have households with a debt-to-GDP ratio of more than 70%. Investors fear that as rates rise, these households will struggle with their debt service obligations, which could create a major constraint to consumer spending. It might be a dangerous cocktail, should the aforementioned decoupling between economic activity in the West and exports from Emerging Asia persist.

“This remains Asia’s number-one risk at the moment: better US data that pushes up global interest rates but delivers little upside to the region’s exports,” HSBC’s Neumann said. At the same time, “there are no compelling reasons to expect that long-term interest rates will quickly return to the average level of 2% observed during the mid-2000s”, the IMF recently remarked, giving Southeast Asia some time to adjust.

However, as time goes by, Asean leaders should think about their growth strategy rather than simply observe global economic developments. As a wise Chinese proverb says: “Do not fear going forward slowly; fear only to stand still.”