The Indonesian government is considering the chemical castration of child sex offenders, but the plan has provoked controversy among doctors, rights activists and even some anti-paedophile NGOs

In October last year, the body of a nine-year-old schoolgirl was found in a cardboard box in Jakarta’s western suburbs. A 39-year-old man confessed to raping Putri Nur Fauziah before strangling her with the cord of a mobile phone charger.

It was the latest in a series of child sexual abuse cases that have stunned Indonesians. A 24-year-old factory worker from West Java was charged in May 2014 with sexually abusing 73 young boys at a public bath. Also in 2014, an elderly man was arrested over the sexual assault of ten children in the same state.

“We are very concerned about child molestation abuse cases. This phenomenon has reached extraordinary levels,” Attorney General H.M. Prasetyo told reporters after a cabinet meeting in late October.

“It has been agreed that there will be additional punishment in order to make people think a thousand times before doing this,” Reuters reported Prasetyo as saying. Indonesia’s top ministers had decided upon a contentious method for tackling the problem, the attorney general explained: the chemical castration of child sex offenders.

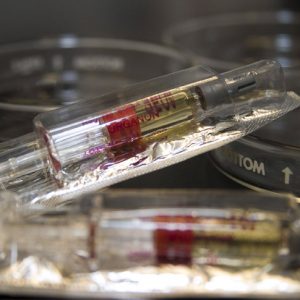

If it goes ahead the government’s proposal, to forcibly ‘castrate’ paedophiles by injecting them with female hormones, would make Indonesia the first country in the region to adopt the practice. South Korea, Russia, Poland and several US states already have similar mandatory measures in place.

The government-funded National Commission for Child Protection (Komnas Anak) has thrown its weight behind the plan. Its chairman, Arist Merdeka Siriat, told the Jakarta Post that Indonesia is experiencing a “state of emergency” when it comes to the sexual abuse of children. “Many children have died, while some are suffering due to these crimes. This severe punishment will make people think twice before committing these crimes,” he said.

And the NGO Indonesian Child Protection Commission (KPAI) has released a number of supportive press statements, with its chairman, Asrorun Ni’am Sholeh, saying that disregarding human rights was “justified under certain circumstances for the sake of retribution through legal mechanisms”.

However, human rights organisations such as Amnesty International have condemned President Joko Widodo for embracing the populist move. Widodo has said that he would use his presidential powers to amend the relevant laws by issuing a perpu, or government regulation in lieu of a law. At the time of writing, he had not yet done so, but Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection Minister Yohana Yembisa had told local media that her ministry had been assigned by the president to draft the policy.

Papang Hidayat, Amnesty’s Indonesia researcher, called on the country’s leader to abandon the proposal while it is still in the debating stage. “Physical mutilation should never be a form of punishment. So-called chemical castration may be a treatment option if discussed by patient and doctor… and if consented to by the person getting the treatment,” Hidayat said. “Turning it into a punishment subverts this approach and would require doctors to provide treatment in the absence of clinical judgement but because legislators demand it.”

Don Grubin, an emeritus professor at Newcastle University’s institute of neuroscience, oversees a UK Ministry of Justice programme where imprisoned sex offenders volunteer to take a course of anti-androgens, or submit to injections, which lower testosterone levels. “The effect is what you would expect – a reduction in sexual interest and behaviour, and a reduction in sexual fantasy and urges,” Grubin explained. “There are also side effects, however – breast growth, hot flushes, night sweats and bone thinning, [which is] usually the most troubling.”

The prison programme has been successful in helping many offenders manage their sexual desires, with many “no longer bothered” with sex and seeing a reduction in violent arousal, according to Grubin. However, as he pointed out, there have been no robust medical studies carried out to prove the efficacy of the treatment. “To do so would require randomising high-risk sex offenders to a medication or no medication group, which is not likely to be acceptable by ethics committees or governments,” he said.

Grubin argues that doctors are not agents of social control and should not be made to carry out such measures in an effort to cure societal evils. “If doctors forget that their primary duty is to the patient, what is to stop them from becoming involved in torture, for example?” he said

According to End Child Prostitution, Child Pornography and Trafficking of Children for Sexual Purposes (ECPAT) Indonesia, there are an estimated 40,000 to 70,000 child victims of sexual exploitation in the country each year, and approximately 100,000 child trafficking victims annually. A fraction of these are reported to authorities; of those, only a small number result in arrests or the conviction of offenders.

Ahmad Sofian, the national coordinator for ECPAT Indonesia, said that many thousands of cases are reported in the media each year, but in 2014 the courts handed down decisions in only 64 child sexual exploitation cases. Although he said that number was likely to have increased in 2015, it means that only a tiny proportion of those committing child sex offences would face the punishment, diluting any deterrent effect.

Sofian argues that the government needs to focus on rehabilitation of child sex offenders – treatments in other countries include the use of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy – as well as greater preventative measures and comprehensive support for victims. “We work to protect the victims, so I think the government has to do something for the rehabilitation of the victims. Restitution from the offenders is better [than chemical castration],” he said, adding that ECPAT would also favour increasing the maximum sentence for child sex offences in Indonesia from the current 15 years.

Indonesia is not the only country grappling with the ethics of chemical castration. New South Wales, a state in Australia, is considering making it compulsory for those who abuse children. Courts in two other Australian states, Western Australia and Victoria, already have the power to order those assessed as being dangerous sex offenders to undergo the treatment as part of their prison release conditions.

Maggie Hall, of Western Sydney University’s social sciences and psychology department, has argued strenuously against such measures, likening forced chemical castration to medieval punishments. “The effect of chemical castration on the bodies of offenders has a symbolic resonance with the horror that people feel about child sex abuse – we are punishing the part of the body of the offender that was used to commit the offence – rather like the cutting off the hands of thieves,” she said. “However, most civilised cultures recognise that this kind of punishment is not helpful without a recognition of the need to rehabilitate.”

While oft-referenced studies from Scandinavia suggest that voluntary chemical castration programmes can cut rates of reoffending from 40% to 5%, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists has argued that studies of sex offenders are beset with methodological issues, while reviews in the British Medical Journal and elsewhere have questioned the strength of the evidence.

According to Hall, chemical castration is probably only effective for those diagnosed as paedophiles – a psychiatric illness characterised by long-term sexual attraction to children aged under 13 and acting on such urges – who make up a small proportion of sex offenders. “What we know about child sex offenders is that a very large proportion of them are family members and often not paedophiles but ‘opportunistic’ offenders. Also, the motivation for the offence may be power and domination, so taking away their ability to become sexually aroused may not prevent further offending,” she said, adding that her primary objection to the wholesale use of chemical castration is that it may give the public a false sense of security.

Ahmad Taufan Damanik, the Indonesia representative on children’s rights to the Asean Commission on the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Women and Children, said the government was scrambling to appear as if it was doing something to tackle the rising number of sexual crimes committed against children. He added that he did not expect the policy to be implemented any time soon.

“This shows that the government has no concrete grand design or planning on how to solve the problem,” Damanik said. “Therefore, they are panicking [over] the increasing number of cases and have come up with a very extreme idea of punishment.”

Keep reading:

“The forgotten men” – Huge numbers of males are raped in Cambodia. So why do these horrific crimes remain largely ignored by rights organisations and the media?