While the junta has high hopes for the Eastern Economic Corridor, some consider the project little more than a stop gap measure that will ultimately fail to address the underlying symptoms of the country’s poor economic performance

Once the poster boy for Southeast Asia’s economic miracle, Thailand’s economy is now lagging behind its increasingly impressive neighbours.

Since General Prayut Chan-ocha initiated a military coup in May 2014, private investment into Thailand has nosedived, with foreign companies instead choosing to set up shop in the more attractive developing economies of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines or Vietnam.

In fact, foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP has averaged at 1.6% on an annualised basis since Prayut’s coup, half the annual level achieved in the ten years before the change in leadership, a period that included the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis.

[manual_related_posts]

But the junta has a plan to dramatically boost investment into the country and, by extension, change the fortunes of the underperforming economy.

Acutely aware of the need to move beyond labour-intensive manufacturing, in February, the junta approved legislation that aimed to boost investment in the eastern provinces of Chachoengsao, Chonburi and Rayong.

Foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP has averaged at 1.6% on an annualised basis since Prayut’s coup, half the annual level achieved in the ten years before the change in leadership

Referred to as the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) bill, the legislation aims to encourage greater investment from foreign companies with expertise in computing, robotics and other sectors that make use of the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ by offering investors an exemption on income tax of up to 15 years, a flat-rate 15% personal income tax rate for foreign executives working for regional businesses in the EEC and 99-year land leases.

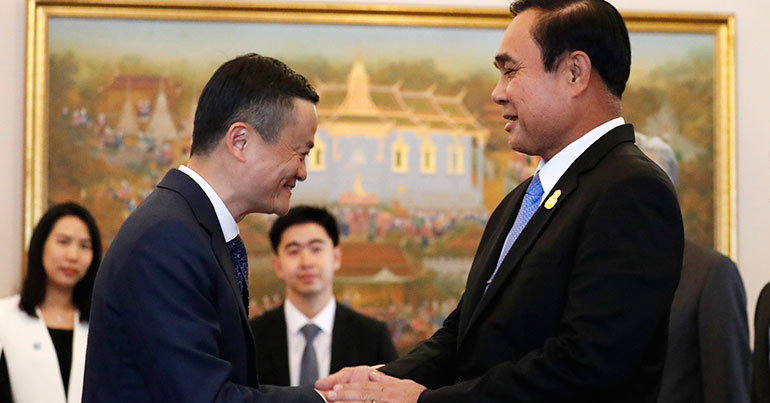

Having already pledged $45 billion towards major infrastructure projects in the corridor and secured more than $320m of investment from Chinese e-commerce giants Alibaba, the junta has high hopes for the scheme.

By exposing Thai companies to the advanced technologies and know-how of foreign firms, the junta believes the scheme will help the country escape from the middle-income trap, enabling it to overcome a skills shortage that has long prevented it from advancing to the next stage of economic development.

However, analysts say that the very nature of being caught in a middle-income trap means that Thailand’s economic problems are the result of deep structural shortcomings – namely poor infrastructure, an underperforming education system and political instability – that can’t be fixed overnight.

***

The EEC Act alone is not, and cannot be, a panacea to all Thailand’s regulatory problems

Southeast Asia Globe caught up with Pavida Pananond, an associate professor of international business at Thammasat Business School in Bangkok, to discuss the challenges facing the Eastern Economic Corridor project, what needs to be done to maximise its impact, and why it shouldn’t be seen as a cure-all for Thailand’s economic ills.

In your opinion, what are the main challenges that the scheme faces?

First and foremost is implementation. Although the EEC has the right strategic vision, implementing all the steps will not be easy. For example, upgrading the infrastructure will take some time as it involves complex issues, such as land reclaim.

The second key challenge is how to raise Thailand’s attractiveness for more sophisticated foreign direct investment (FDI). When multinational companies look for investment locations, the most important factors for them are whether and how these locations provide advantages over other locations. Because the EEC wants to attract more sophisticated industries and activities, Thailand has to make sure it can provide more than cost advantages. It needs to make sure that it offers advanced domestic skills, as capabilities will certainly be another key challenge.

In terms of regulation, what does Thailand need to do to ensure it attracts the right type of investment into the EEC?

Thailand aims to use the EEC as a one-stop investment location in which regulatory hurdles and obstacles to efficient public services can be overcome by the magical EEC Act. But what Thailand should be doing is addressing and remedying the hurdles on a broad basis so that regulatory costs to all foreign investors are reduced. The EEC Act alone is not, and cannot be, a panacea to all Thailand’s regulatory problems.

One of the most important regulatory issues in Thailand is the high rate of redundant laws and regulations, which increases the cost of doing business and reduces transparency. If this complexity can be reduced, doing business in Thailand would be made more attractive.

To what extent is there a danger that foreign companies won’t actively invest in the development of Thailand’s economy and will simply use the EEC as a short term profit farm? What does Thailand need to do to maximise the amount of technology transfer from foreign to local companies?

To attract and maximise the benefits from more sophisticated inward FDI, local players need to have a level of capabilities that allows them to withstand and interact with foreign multinationals, either as competitors, buyers or suppliers.

Simply forcing foreign multinationals to transfer technology to domestic firms would not work if domestic firms were not at a level sophisticated enough to absorb the information being transferred.

What lessons did the country learn from its foray into the automobile industry? What mistakes should it try to avoid this time around?

Despite being one of the most important industries that contribute to the economy, the automobile industry in Thailand is heavily dominated by foreign multinationals. Domestic players and suppliers rarely feature in the more sophisticated areas of the value chain.

One key lesson should be how to foster and develop domestic suppliers that are skilled enough to take a more active role in the value chain of the global industry.

To what extent could the EEC help the country overcome avoid falling into the middle income trap?

While the EEC is a step in the right direction, it must not and should not be seen as the panacea for Thailand’s economic ills, namely being caught in the middle-income trap and suffering from low productivity and low efficiency.

To move Thailand into a more knowledge-intensive and innovation-driven country, a lot more needs to be done, particularly with regard to raising domestic skills and capabilities and reducing regulatory bottle-necks.