Currents of time

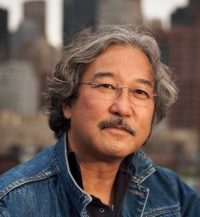

In 1991, National Geographic photographer Michael Yamashita traversed the length of the Mekong, from source to sea, in a groundbreaking trip documenting the communities for which the river was so central to life. The Globe sat down with Yamashita to reflect on his journey almost three decades on, as well as hear his thoughts on the dams and environmental degradation blighting the river today

By Andrew Haffner

Photographer Michael Yamashita has been shooting for National Geographic magazine for over 30 years, combining his dual passions of photography and travel. After graduating from Wesleyan University with a degree in Asian studies, he spent seven years in Asia, which became his photographic area of specialty. Upon returning to the US, Yamashita began shooting for National Geographic as well as other American and international magazines and clients. His pictures are currently enjoyed by over 1.6 million Instagram followers here, while his work can be viewed and purchased on his website.

A river can be timeless, but on no two days will its flowing course ever truly be the same.

So it goes on the mighty Mekong. For thousands of years, this river has wound its way through much of Asia, shaping the land and lives of the people that inhabit its enormous basins. But for all the millennia of change in the Mekong’s waters and along its banks, maybe no time has produced such a rapid transformation for the river as the past few decades.

Michael Yamashita has witnessed much of that first-hand – documenting it through the lens of a camera.

In 1991, the National Geographic photographer began traveling the length of the Mekong, as it winds through six countries over 4,350km from its source in China’s Tibetan plateau, to its mouth at the South China Sea near Ho Chi Minh city in Vietnam.

For more than two years, this journey brought him through countries only just reopening to foreigners after decades of war and strife. He timed his route along the dual considerations of nature and bureaucracy, organising his shooting schedule across rainy and dry seasons and keeping tabs on where he could legally cross borders.

Yamashita eventually published this work in National Geographic’s “A Haunted River’s Season of Peace”, a sprawling 1993 article that gave readers a glimpse at scenes rarely witnessed by outsiders. Two years later, he published more of his photography in a book simply titled Mekong, which he described as a “social history” of the river and its people.

The 17th of December marks one year since the Lower Sesan II Dam was opened, displacing hundreds of communities living along the river in Cambodia, and with the 25th anniversary of the publication of Mekong approaching in April, Yamashita spoke with the Globe about what he saw on his journey back in 1991, as well as how much the river has changed in the years since.

The world you captured in these photos is really striking, especially when we compare these places through the years. What did it mean at the time to embark on this kind of trip?

The story hadn’t been done – period. Nobody had been from the source to the mouth [of the Mekong].

Depending on which country opened up next, that was where we went. It wasn’t a linear thing, start in one place and end up in the delta, it depended on who gave us permission. Laos was closed to foreigners, Cambodia – other than [when King Norodom Sihanouk was] returning, there were still soldiers all over. Even at Angkor Wat, there were landmines and not anybody could just go there, you had to have special permissions while the UN was there working on the temples repairing war damage.

In Vietnam, I was the first one in the delta since the war, to the point where we were debriefed by the [US Department of State] when I came back. Nobody had seen it, and they wanted to see what it looked like, so myself and the writer were invited to the Pentagon to be debriefed in front of this huge crowd of experts on Asia.

So it was kind of groundbreaking that we got in all those places and did a story. We’re coming up on thirty-year anniversary this coming year, but it really was virgin territory then and I think the photographs reflect that. There was no such thing as a tourist, that’s for sure.

Nowadays, it’s like tourist Disneyland. I was shocked to go back to Angkor Wat and see this sea of tripods in front of that morning shot. Back then, I would’ve been the only person, and now there’s about 100 Chinese tourists that have gotten up for the sunrise, and are still getting beat there.

People tend to live with the river in very different ways depending on where they are along its course. What kind of lifestyles did you see as you travelled along the course?

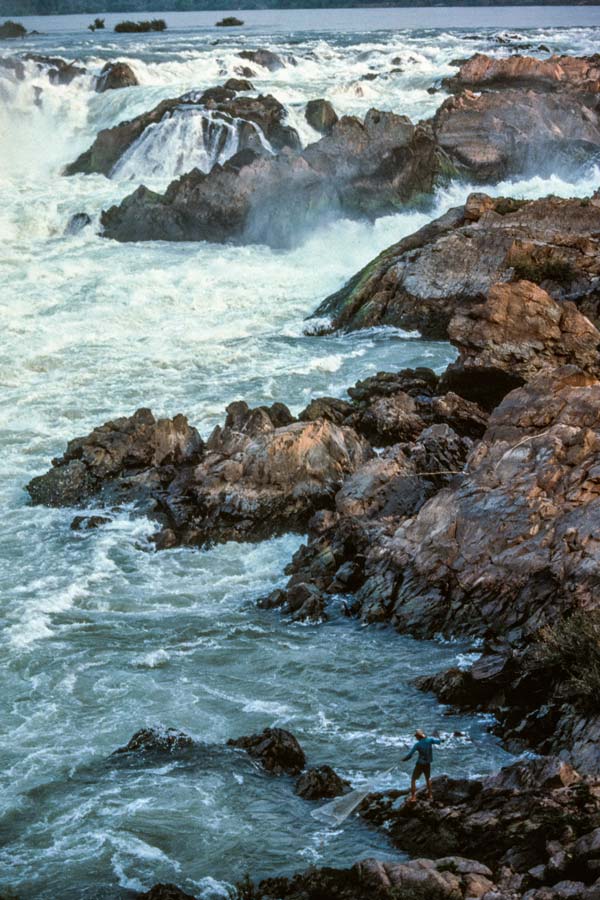

For the first thousand miles in China, it’s really only in the last 100 where people use the water for anything, at least in those days. The Tibetans – mostly in Tibetan territory right through the northern areas of Yunnan – it’s very sparsely populated and the river runs really rough. These rapids and deep gorges make it pretty much unavailable for anything but irrigation, and it’s also a tough area to be growing crops, so you don’t see it used for much at all.

No boats in those days, and there were the Tibetans who believed in water burial and didn’t eat the fish. That’s part of the deal, you chop up the dead bodies, throw them in the water, and the fish feed on them. The souls go to an afterlife, but, in return, the Tibetans don’t eat the fish.

Then you get further down, and for about 100 miles to the Laos border, suddenly you’ve got people using it for all kinds of stuff. Fishing of course, but still no big fishing, and boats were still really sparse. There was only one bridge across that part of the Mekong at that time but it was just one lane, just ridiculously small. I was there fairly recently and now there’s at least three big bridges that cross the Mekong there.

There were also no dams then. In 1991, maybe 1990, I photographed the Manwan Dam being built, and that was the first real one on the Mekong. So it’s also a shock to read there are so many more today, and on the tributaries too.

As you came further down the river, Laos was also quite sparse aside from small cargo carriers going up and down. There was some fishing done on a large scale, but really, the Khone Falls [in southern Laos] is like the demarcation line. Once you got below Khone Falls, you get into Cambodia – and things went berserk around Phnom Penh, where the river was being used for everything. That continued as you went on to Vietnam, and, also there, the river was, compared to upper regions, just so much going on. It was incredible, the floating markets, and everybody benefiting in some way by the river, their lifestyles all connected with the river.

It sounds like in those days there was no inkling of the dams, or these low-water-level issues that we’re seeing now.

No, there was optimism everywhere. And the banks – we did, where we could, the wet and dry seasons, to compare the two – of the river in the dry [season] were just green and everyone was out there tending crops. The wet season had the huge contrast with rising waters, and you could see the difference in the banks when all those metres were exposed. I guess now they’re being exposed all the time, which ruins the basis for that agriculture which is the rich buildup of soil on the banks. We also recently did a story on the Irrawaddy, for the [charitable organisation] Nature Conservancy last year, and they’re having the same issues there. So it seems to be focusing on the same issues on another huge river where people, again, really depend upon it for their livelihood.

But even then, you could see the beginnings of some problems. There were stretches that were quite polluted with sewage. And everyone still looks at a river as a cleansing thing – you throw the garbage in and forget it. It’s easy to do that with rivers, as it all disappears with the current.

It becomes somebody else’s problem.

The Mekong, like all rivers I think, is a dynamic thing, a living thing. Did you feel any familiarity with it, any kind of bond by the end of your journey?

Yes, of course. You live these stories, and I was on this one for at least a couple years, so you become very close to the people, the issues. I felt very sympathetic toward the Cambodians and, of course, the Vietnamese. Just to be there and know the stories of these places with plenty of war history, that was significant. I subsequently adopted my daughter from Vietnam because of that experience there. I really liked the character, the personality of the Vietnamese I knew, who I personally found to be quite peaceful and gentle.

So in 1995 we adopted my daughter, who is now 24. She’s just about ready to get out of college, so that’s about as personal as you can get, in terms of the connection to countries along the river.

So now, when you read about what’s happening to the river when you come back to visit – is it difficult to see some of those negative changes that have happened in the years since?

Yeah. And for people along the river, many of them feel so helpless to do anything about it. Here [in the US], there’s a big movement to limit plastic, of trying to get large numbers of people to commit to banning the use of plastic bottles, and other plastic products. These are things that now, on a very grassroots level, people are trying to do something about. But the process in places like Cambodia and Vietnam, where the money is not quite there – that’s a difficult ask for people to do any kind of sacrifice at all. I don’t know what the answers are, but it must be incredibly frustrating to be one of those losing their livelihoods, thanks to overfishing and climate change.

Right. And a lot of this is due to these huge geopolitical events happening, so for someone living, say, in a floating village, it’s a whole different world.

Plus there are people profiting big-time, and these are the ones in power. These things [dams] don’t get built unless there’s government willing to build them. It’s this very short-sightedness where people are only thinking of their own circumstances and not of the future, especially for their children, who will have hell to pay.

I just hope they’ll preserve something of what it used to be. I don’t have an answer for what it’s going to be, or what it could have been. I mean, the population alone in the last 30 years has just ballooned, and that makes these things harder too.

So you saw how things were 30 years ago and how much it’s all changed since then – it seems impossible to guess how much it could all change again, but do you have any thoughts for the future of this river?

We focused on some of the issues, as well as the beauty of it and the cultures along the river. And now, 30 years later, everybody seems to be predicting the doom of the fishing industry. And with the droughts and the climate change, somebody better do something quick – there are so many people who depend on this resource, and we need to wake up.

Everybody individually should try to do their part. But the ones who are getting hurt the most are not in the position to be making changes, because they’re the poor ones. They’re already making a meagre living on, say, fishing, and now not even that is open to them.

Definitely. And some of these people are close to us here in Phnom Penh. Did you spend much time in Cambodia? What was your impression of the relationship of the people and the river back then?

We still had the turning of the Water Festival, and [King Norodom Sihanouk] had just returned so the whole city was buzzing. They had about a billion second-hand motorcycles being sold from Singapore, and everyone had one and it was absolute chaos, because there was only one traffic light in Phnom Penh. It was such a joy to be there because it was this really celebratory mood. That’s when I shot a lot of the fishing [photos], and ended up spending quite a chunk of time there. For me, that was the highlight.

One of the things that I spent a lot of time on in Cambodia was the Tonle Sap and the incredible fishing that took place on the river, especially when the waters reversed. You read now that it was an all time low for water levels, or that there’s hardly any fish to catch because the low waters have killed tonnes of them – as well as with the overfishing, climate change all those other reasons – and that, for me, is the saddest of it all.

When I was there, I was seeing catches as big as you’d get in the ocean, they were pulling in tonnes of fish in these huge nets in configurations on the river. I have pictures of them pulling in fish the size of tuna, huge Mekong catfish and all manner and kind of other fish, in so many different ways of catching them. So that is really sad that that is going away and not coming back. That is huge, especially for Cambodia, where so much of the protein depends on that.

Michael Yamashita has published 13 books, mostly inspired by his 30 National Geographic stories. His passion for the Tibetan world led him to shoot five stories for Natgeo: Our Man in China; Joseph Rock, The Forgotten Road, Tibetan Gold, Jiuzhaigou; Mystic Waters and Journey to Shangri-La which resulted in the book, Shangri-La [along the tea road to Lhasa]. Yamashita’s most recent exhibitions, currently travelling the world, are focused on the theme of the Silk Road Journey following both the overland and maritime silk road routes, with over 20 exhibitions from the Jimmy Carter Center in Atlanta, Georgia, to Singapore, London, Hong Kong and throughout China.