The film opens with dark gray smoke billowing from twin stacks soaring high above a cityscape, the sky only slightly less gray than the pollution that rises to meet it. Cut to a crowded Asian street, filled with dated vans and face-mask-wearing drivers astride motos, and then flames and smoke spewing from open trash piles set on fire. These images come from a UN PSA film released this year, but the imagery has long been linked with the dangers of air pollution.

The short video’s conclusion that “the world has the science, technology, and funds to reduce pollution for a cleaner future” is written over images of solar panels, windmills and trees lining a clean lake.

The message is as clear and recognisable as the scenes it shows: conventional fuels edge us closer to climate catastrophe; green energy is the solution.

Demand for electricity in Southeast Asia is expected to grow by two-thirds by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency, and countries are scrambling to meet demand through multiple sources of energy, both clean and dirty. The forerunner in the Mekong River basin – the hydroelectric dam – has been seen as the Wunderkind for electricity: a relatively-powerful green energy source that makes the most of nations’ natural geography and resources.

Hydropower dams generate power by the flow of water through turbines; the more water the more power, so in theory, if built on a sloping river, dams produce power by letting nature do its thing, with little to no atmospheric cost. Compared to coal, which is dug from the bowels of the earth, dragged across borders for combustion in smoke-spewing plants and is the most dominant energy generator in Southeast Asia, hydroelectric dams seem like a sound investment for both pocket and planet.

But a recent study of hundreds of dams in the Mekong River basin found that one in five may actually emit equal – or even more – greenhouse gases than fossil fuels. And that’s not including all of the pathways that lead to emissions.

According to the study’s lead author Timo A Räsänen in an email to Southeast Asia Globe, if all emissions pathways were considered, the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions would be larger.

How much of these harmful gases gets released depends on the dam’s design and surrounding landscape. The reason why dams emit GHG?

It’s the trees.

Most high-level scientific and policy documents continue to presume zero to minimal emissions from hydropower

Danny Cullenward, policy director at the Carnegie Institution for Science

No smoke, still fire

The problem is how dams are made. To create the water reservoir that sits behind the gates of hydro projects, it’s often necessary to flood landscapes. Carbon is locked up in trees, grasses and other vegetation, and when submerged, this organic matter rots in the reservoir, producing carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane.

Burning coal, gas or oil also produces these gases, but the important thing is which ones. The majority of the GHG produced by fossil fuels is carbon dioxide, whereas 90% of hydroelectric dam’s GHG is methane – and it’s this gas that we should be worried about.

According to data from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the top scientific body studying climate change, methane is behind one-fifth of the rise in average global temperatures during the past century, with concentrations in the atmosphere increasing 150% since the Industrial Era. The main culprits so far have been fossil fuels, wastewater treatment plants, landfills and gassy livestock.

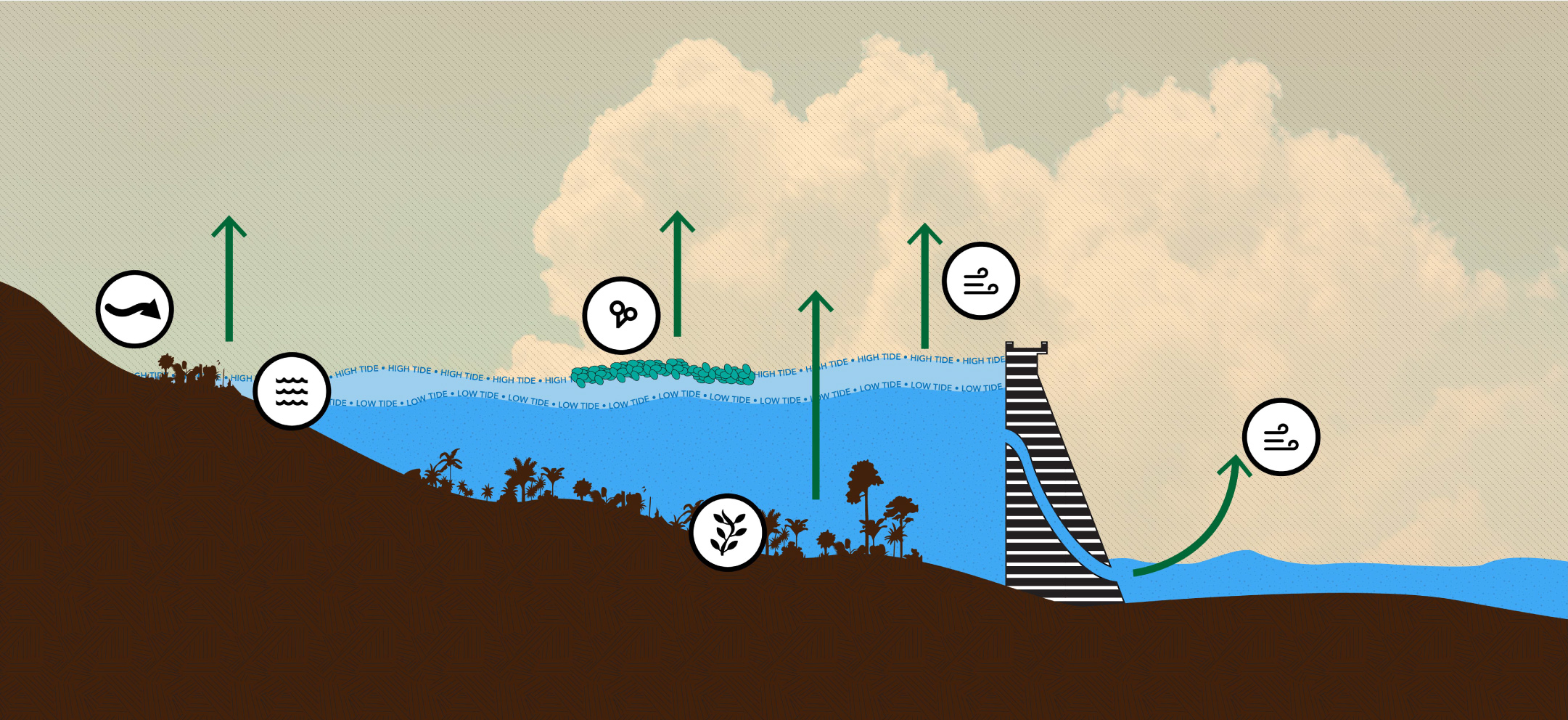

How dams warm the world:

greenhouse gas emission pathways from water storage reservoirs

Click or tap the hotspots below to zoom in and see more details.

Runoff

Water entering reservoir adds rotting plant material

Water Level

Plants on the bank grow as the water level drops and die when it rises

Surface Plant Matter

Plankton and leafy plants release gases as they decay

Flood

After the reservoir is filled, flooded plants and soil rot

Diffusion

Gases are released from decomposing plants and soil

Degassing

When water is released the drop in pressure drives release of gases in the water

Methane is a much more potent gas than carbon dioxide, packing a bigger punch in a shorter time. Over a century, methane traps 34 times more heat than carbon dioxide, and 86 times more in the first 20 years.

For Danny Cullenward, research associate at the Carnegie Institution for Science within Stanford University’s Department of Global Ecology, “decisions about emissions in the next 20 years are critical to achieving the global Paris goal” –making large emissions of methane during this window “highly problematic”.

The “Paris goal” refers to the Paris Climate Change Agreement, a deal made in 2016 between 185 states to reduce their carbon emissions in order to limit global temperature increase from pre-industrial levels to “well below” two degrees Celsius. An increase of two degrees would lead to longer heatwaves, increased rainfall, reduction in available freshwater and crop yields, higher ocean levels as well as widespread coral bleaching.

In October 2018, the IPCC’s special report sent humanity a clear message: “this is not a drill”. Current emissions rates could mean global temperatures exceed a 1.5°C rise as soon as 2030, putting us on course for a 3-degree warmer world – meaning longer droughts, fiercer hurricanes and sea level rises of up to two metres by 2100. A tide mark this high could put Southeast Asian megacities such as Bangkok, Manila and Jakarta underwater.

This is not a drill

So every source of emissions needs to be accounted for when trying to predict – and avert – future catastrophe. According to Cullenward, GHG emissions from dams are currently going uncounted, because “most high-level scientific and policy documents continue to presume zero to minimal emissions from hydropower.”

Unfortunately for Southeast Asia, geography plays a part in its higher hydropower GHG emissions. The higher the water temperature, the more rapidly vegetation rots, forms and releases gases, making dam reservoirs in the tropics responsible for more GHG than those in temperate climates.

What’s more, the loss of trees to dams is a double whammy for the atmosphere: fewer trees to absorb these emission mean not just the release of methane through the rotting of trees and vegetation in reservoirs but more carbon dioxide remaining in the atmosphere.

Of all the dams slated for the Mekong River basin, those in Cambodia look set to deal the atmosphere the biggest blow. Not blessed with the valleys and gorges of its northern counterparts China and Laos, which enable creation of natural dam reservoirs, Cambodia’s lowlands will house some of the largest reservoirs in the basin. Projects in Cambodia are not the most powerful, but could well be the most harmful – they are in the top ten for highest emissions per square metre of surface area due to their size, including the Lower Sesan 3, Lower Srepok 3, and contentious juggernaut Sambor dam. For Räsänen, “the large surface area of a reservoir combined with location in a warm climate and low power [capacity] is a concern.”

When it comes to reservoir size-to-energy output, worst of all would be the 620km² Sambor dam reservoir, set to be the largest in the Lower Mekong Basin. Not only will it have the largest emissions output, but the authors of the project’s impact assessment warned Sambor could “kill the Mekong” by blocking fish and sediment flow into the river – spelling a mass die-off of fish and widespread hunger for the millions who depend on them.

Stemming the tide

There are a number of ways to reduce emissions from dam reservoirs, including thorough removal of vegetation from around the reservoir site before inundation, which Räsänen describes as fundamental.

Unfortunately, there’s a poor record of removing vegetation from around sites in the tropics, as was the case at the Laos’ Nam Theun 2, where the project’s largest shareholder deliberately misled the Science, Technology and Environment Agency in order to dodge the time and expense of full clearance, according to the authors of the book Dead in the Water: Global Lessons from the World Bank’s Model Hydropower Project in Laos.

“Purely from the climate perspective,” says Räsänen, “hydropower should be planned to maximise the energy production and minimise the reservoir surface area.”

For Cambodia, this would mean scaling back on its hydro ambitions and following in the footsteps of its eastern neighbour, notes nonprofit EnergyLab Cambodia country director Bridget McIntosh.

“Vietnam is an excellent example of a country taking advantage of small hydro,” she told Southeast Asia Globe.

Beyond the threat posed to the planet, the cracks in an energy strategy heavy on hydro are already showing. This year, Cambodia has faced rolling blackouts since March due to low water levels in dam reservoirs after the dry season. Dam reservoirs are also vulnerable to the effects of climate change, particularly drought, which could intensify and spread to cover 96% of Southeast Asia by 2100, according to the latest report from the UN Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

When reservoirs run dry, other energy sources must pick up the slack, meaning hydroelectric dams are never fully replacing fossil fuels. There’s hope this may change in the future as hydro and solar could be used together to deliver more megawatts per metre. “I am excited by the prospects of floating solar on existing hydro reservoirs,” says McIntosh.

Many researchers agree that the potential for dam reservoirs to emit harmful GHG should be understood by policy makers, and taken into account when conducting environmental impact assessments.

Could hydro make or break the Paris targets?

Under its Paris Agreement pledge, Cambodia, one of the Mekong’s most ambitious dam-builders, has little more than 15 years to reduce its current emissions by over 25%. While hydropower remains an attractive option, it takes much more time to implement than other renewables – time which the nation does not have.

As Cullenward points out, meeting the Paris goals “requires an all-hands-on-deck effort across the world, including reducing methane emissions from dams”.

For now, the lack of impartial, international scientific assessment on emissions, according to Räsänen, means that the major challenge to facing down the threat of climate catastrophe remains that “we need to make urgent decisions with imperfect knowledge.”

But “if people cannot come together to act in the best interests of their families and the future,” says Cullenward, “It might well be too little too late.”