Sitting cross-legged on the floor of an office in northwest Cambodia, Narith cuts a slight figure for his 21 years of age. He is polite but somewhat withdrawn as he prepares to recount the series of events that led to his imprisonment in November 2008.

His story begins as one might expect of a teenager who ended up on the wrong side of the law. “I had a lot of bad friends,” he says. “My parents warned me not to go out at night… not to fall into the wrong crowd.”

Narith, who asked for his name to be changed, was 16 when he and two friends broke into a shop and stole a mobile phone. The next morning, police arrived at his home, where he says he was physically assaulted before being arrested on charges of robbery. “After I was arrested the policeman called my family and asked for some money or I would be sent to prison,” he says. “After three days my parents told the police they didn’t have much money, so I was sent to prison.”

Narith was initially sentenced to three years imprisonment for his crime, the minimum sentencing in Cambodia for robbery and extortion under Article 34 of the Untac penal code, which mandates prison sentences of three to ten years. What is unusual about his case, however, is that prior to completing the three-year prison term, an additional two years were added to his sentence. He was then sent to Phnom Penh and imprisoned while he awaited an appeal, which was granted six months before his five-year term would have been complete.

The reason for the extended sentence is not entirely clear, but Narith alludes to corruption and the misfortune of stealing from a well-connected person. “If I had money, I would have recieved a lesser sentence, or I would have even stayed out of jail,” he says. “The victim was not satisfied with the three years I had served for my sentence.”

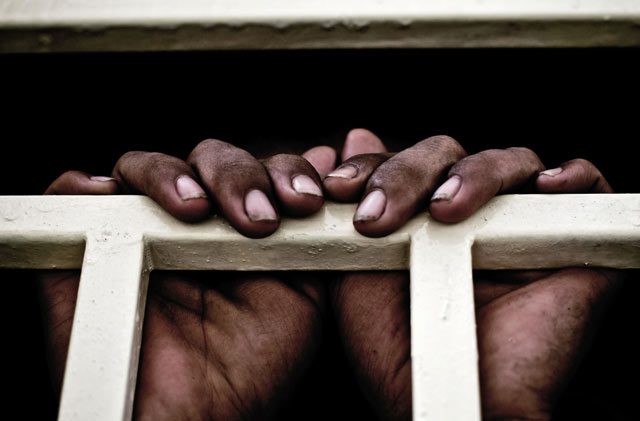

Cambodia does not have a separate juvenile justice system, meaning children and young adults between the ages of 14-18 are tried in adult courts and held in adult prisons. Narith’s story is one of many in a country that routinely sees juveniles who have committed petty crimes end up in a penal system that is already at more than 170% capacity.

“Juveniles are often held in pre-trial for petty crimes such as theft or minor drug offences and then handed disproportionate sentences at trial,” says Naly Pilorge, director of Licadho Cambodia. “In its totality, the Cambodian prison experience is a psychological time bomb, particularly for young people. Abuse and corruption are rife and only those with money are entitled to certain ‘privileges’ such as extra recreation time, decent food and regular family visits.”

Approximately 60 of the estimated 1,200 inmates at Siem Reap prison – where the human rights situation is dire and access to clean water, sanitation, healthcare and protection from abuse is severely limited – are classified as children. Despite the availability of youth-only cells, overcrowding means that juveniles can end up with adults.

“While the government has made a positive step by separating children into their own cells, they remain confined in the same prisons as adults,” says Billy Gorter, executive director of This Life Cambodia (TLC), a community development initiative that supports juvenile prisoners and helps reintegrate them into society. “When there has not been enough room in other cells, sometimes adults have been placed in the cells with juveniles.”

Once juveniles enter the system they are vulnerable to abuse from guards and other prisoners. A recent report released by Licadho reveals that prisoners who break prison rules can be shackled, beaten or kept in their cells for extended periods of time. New prisoners are also often subject to initiation beatings, which are carried out by groups of inmates designated and directed by guards.

“All of us got physical punishment. We were hit. One of my friends was bleeding on his head, another one collapsed because he was kicked in the back,” one youth says about his time in a Cambodian prison. “If we respected the prison rules and regulations, we could live there peacefully. But when I first arrived at the prison, they beat and hit me.”

In 2002 the Cambodian government drafted the Juvenile Justice Law, which is said to incorporate reform around non-custodial sentencing of minors and their diversion from the traditional justice system. To date it remains in parliament and any specific details of the law have been kept from the public.

“The passage of the new Juvenile Justice Law, which has been in the making for several years and which was once rumored to be introduced this year, appears to have stalled indefinitely,” says Pilorge.

Even if the law were passed in 2013, it would be too late for Narith, who is clearly remorseful for his actions. The amount of time it will take for him to come to terms with the injustice of his punishment, however, is less certain.

“I think the sentence was [harsh] for me,” he says. “People [with money] who commit more serious crimes than stealing a phone will receive a far shorter sentence. For me, I returned the phone to the victims, yet I got five years. It is not fair.”