When AirAsia official V. Raman Narayanan talks at seminars and conferences, he sometimes uses a version of the following anecdote: “Imagine you are the owner of a small business in Singapore. […] You can now drop off your son at school in the morning, hold a meeting at your office, then board a flight to have a lunch meeting with associates in Kuala Lumpur, then fly to Bangkok to meet with potential business partners there, then take an evening flight back to Singapore and arrive in time to kiss your son goodnight.”

Narayanan, who is based in Jakarta and acts as group head of Asean affairs and government relations for AirAsia, has other similar narratives, some even based on real individuals whose lives have benefited from an increasingly linked-up region. In this case, it is the cheap point-to-point flights that provide opportunities. But the anecdote speaks to a much larger issue that lies at the heart of Asean: connectivity.

“It seems to resonate with audiences,” Narayanan said when asked why he favours the story of the jet-setting business owner. The example makes the case for increased connectivity and its economic benefits much more vivid, he added. “Especially given that more than 90% of Asean’s economy is driven by small to medium enterprises. I suspect it also resonates because of the element of family.”

For most people, connectivity means interaction, whether in business or personal life: The sidewalks we stroll upon to visit neighbours, the global Skype conference call, the roads companies use to transport their goods, the web we surf, the planes we board, the trains we catch, the automobiles we drive.

For the ten Asean member states, the connotations are the same, but there are extra threads that make the word take on both a technical and a symbolic meaning. In other words, if countries within Southeast Asia want their economies to keep growing and developing, and if they want to create a broader community feel, they will have to create stronger links with each other, which means, of course, building the infrastructure at home that makes those links possible.

“In Jakarta, they cannot have more flights in the peak hour. They have already reached the limit of the capacity,” said Eddy Krismedi, an infrastructure officer with Asean. “The infrastructure has not been able to cope with the traffic itself.”

A regionally connected road system won’t work if part of it is missing or needs upgrading in one country. Creative initiatives for tourism will falter if, for instance, ports refuse to accommodate deep-sea cruise ships. The Asean Economic Community (AEC), slated for 2015, takes off on this notion of one hand washing the other. It also means spending a lot of money.

“The idea of Asean connectivity is actually contingent on the success of the larger AEC,” said Shaun Narine, associate professor of political science and international relations at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, Canada. “So much of what is involved in connectivity – such as building and improving the movement of labour, improving transport and trade links, improving internet and other technological connections – are all subsets of the AEC and, indeed, the larger Asean community idea.”

“Right now, intra-Asean trade is about 26% of total Asean trade, which is quite good and a marked improvement over the past 15 years,” Narine added. “However, the bulk of that trade still remains between relatively few states – Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia, with most of it really between Singapore and Malaysia.”

Asean member states have several complementary plans on the table to address the issue of connectivity. Some have more of an aviation focus, others deal mainly with tourism. But the most comprehensive in its scope came to light in 2010 at the 17th Asean Summit in Hanoi. Then, the ten member states officially adopted a connectivity masterplan, which lists prioritised projects and timelines. At the time of writing, many are still at various stages of completion, and some will extend beyond the 2015 deadline for the AEC.

Of the three kinds of connectivity laid out in the plan, “physical” refers to, among other things, poor roads, inadequate ports, inland waterways, incomplete railway lines, aviation facilities, addressing the digital divide and confronting a growing appetite for electricity.

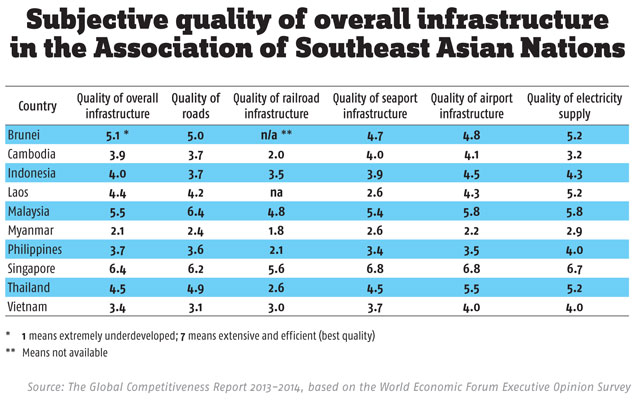

The Asian Development Bank (ADB) says that despite ongoing economic growth in the region, infrastructure lags behind more developed economies – not to mention the average in Asia – and logistics costs remain high. According to 2008 figures used by the ADB in a March presentation, Asean was behind Latin America and OECD countries in phone ownership averages. With respect to roads, electrification and clean water, Southeast Asia is similarly behind. In rail coverage, compared to Africa, OECD countries, Asia as a whole and Latin America, Asean was ranked dead last, though in recent years, the numbers for rail coverage, roads, ports and airports have climbed steadily.

“I think what we want to do is make sure our roads are good enough, so the businesses can reach the port, and transport their goods to different parts of Asean,” said Lim Chze Cheen, head of the connectivity division under the Asean secretariat. Once goods go from port to port, trade facilitation agreements will make the customs process less onerous and duplicative. “We are hoping that by having that particular connectivity, it will cut time, cut costs and simplify documents,” Cheen added.

‘Institutional’ connectivity, the second prong of the approach, creates agreements that will help countries make it easier to free up the movement of vehicles, goods, services and skilled labour across borders. Lastly, for the people-to-people segment, the plan hopes for “greater interactions between the peoples of Asean”, using various communications tools such as websites and virtual learning centres – the details of which are a little vague – and the relaxation of visa requirements allowing for greater travel fluidity within the region.

International tourists may be able, some day, to use one visa to visit all Southeast Asian countries. But promoting intra-regional travel is just as important, as tourists from Asean countries account for more than 40% of overall visits.

The 15 prioritised projects are a mix of hard and soft infrastructure. Some, such as the Asean Highway Network, which seeks to improve roads across the region; the Singapore Kunming Rail Link that incorporates interconnected rail lines that will make it easier to move goods from country to country; and the Asean Broadband network which is a push for wider internet access, are more or less self-explanatory.

Power interconnection, another project, requires building more transmission lines and submarine cables. Each relies to a certain extent on member states to carry out upgrades that are part of the greater whole. The Singapore Kunming Rail Link, for instance, needs Cambodia, Thailand and Vietnam to complete stretches of missing rail.

Others involve mutual agreements to facilitate trade – such as the Asean Single Window, liberalising investment agreements, creating more awareness of Asean within the region and completing studies on topics as varied as the regional visa and a more dynamic port system. The main problem, of course, is funding.

“Resource mobilisation for the realisation of the hard infrastructure is acknowledged in the masterplan,” Kanya S. Sasradipoera, a regional cooperation specialist with the ADB, wrote in an email. “The Asean Infrastructure Fund (AIF) was subsequently established following the call of the Master Plan on Asean Connectivity (MPAC) for an innovative way of resource mobilisation.”

According to a presentation on the fund in December, Asean’s infrastructure projects will require annual investments of about $60 billion from 2010 to 2020, “and this is in addition to national projects with significant cross-border impacts such as airports, seaports and roads to borders”, the presentation said. “In a global environment of increasingly tight access to capital, mobilising finance for these enormous levels of investment has become even more important.”

Aided by ADB loans, the AIF will provide financing to sovereign or sovereign-guaranteed projects, and has already started lending with a $25 million loan to fund power links in Indonesia. The AIF also has a financing plan that would involve allowing central banks to buy investment-grade debt paper using their own foreign reserves as another way of drumming up funds.

The amount of funding required has created scepticism, similar to the scepticism that has surrounded the plan to establish the AEC and its relatively meaningless 2015 deadline –now consistently referred to as a “milestone”. The plan, like the community, will be long-term.

“In this light, the idea of Asean connectivity is aspirational,” Narine said. “As it stands, the ability of the Asean states to truly commit to and see through the infrastructure development required by the MPAC varies wildly depending on the states. Countries that have limited resources and are contending with political upheaval are going to have different and more immediate priorities that may not involve building highways or railways, however sound the idea may be.”

But the benefits are easy to grasp. In the next several years, as the AEC comes together, connectivity will not only help the loving father who wants to make his business meetings and his son’s bedtime, but the tourist who wants to book a vacation, the logistics company that needs to ship products across countries on a tight deadline, and the small firm struggling with power outages. It’s a good thing for almost everybody, so long as they can pull it off.