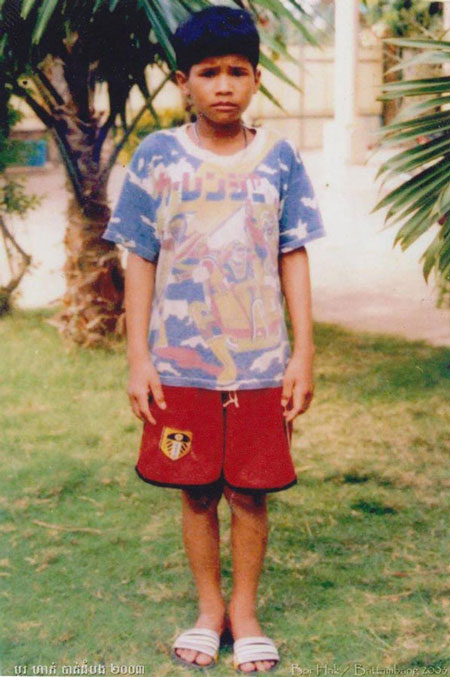

“When my biological father was alive, my family wasn’t so poor, we were above poverty as a family of farmers,” said Bor Hak, a 28-year-old animator at Phare Creative Studio in Battambang, a town in the west of Cambodia.

Everything changed, however, when Hak was just seven years old. His father died and the heavy farm workload passed to his mother, who had her hands full raising a young family.

About a year later, Hak’s grieving mother remarried, to a musician. But that did not improve the bereaved family’s deteriorating financial situation. “Our status began to constantly drop to the point where they sent me and my brother to Thailand,” Bor Hak recalled.

Lacking a proper education and just turned 13, the boy Hak soon found himself exhausted by the man’s world he was thrown into – drained by a succession of arduous labouring jobs, from selling coal to picking pineapples to working in a dried fruit factory to long and back-breaking hours hauling 50kg sacks of rice.

But then lightning struck a second time – not a fatal strike, but life-changing all the same. Almost two years into their stint in Thailand, Hak’s stepdad was badly injured at work. He was forced to go home to Cambodia, leaving Hak and his older brother to fend for themselves in a strange land.

Like many migrants in Thailand, Hak did not have official documentation, leaving him constantly vulnerable to frequent police raids and official clampdowns on the country’s millions of low-wage Cambodian and Burmese workers.

“It was nearly the election day in Cambodia when the police captured all the migrant Cambodian kids in the factory and sent them back,” Hak recalled.

“I didn’t own a passport at that time, so they sent me and other illegally crossing kids to an organisation in Battambang,” he said.

“My brother had a passport, so he was safely sent home. That was when we parted our ways and lost all of each other’s contact.” said Hak.

In his role as executive director of land and housing rights organisation Sahmakum Teang Tnaut, Soeung Saran meets many families facing scenarios similar to Bor Hak’s.

“Many of the families we spoke with lost an income earner to injury or illness and this led to them defaulting on their loans,” he said.

“Often times like this meant that their families had to take on debt, or had to take children out of school to work to pay back the loans,” he explained, adding that families often felt they had little alternative.

“I quit fishing to look after my son, so at that time the house income depended only on my husband”

Hak Lai, 56 year old divorcee

For most Cambodian families, the presence of a father does not just mean a firm or sometimes stern paternal hand guiding the rest of the clan. As usually the main income earner, an ill, injured or absent father can leave a family facing debilitating financial losses.

Some of the devastating consequences can include taking children out of school, houses or property being sold, borrowing money from gimlet-eyed lenders or emigration, according to Am Sam Ath, deputy director of monitoring and protection at the Cambodian League for the Defence and Protection of Human Rights, a non-governmental organisation known by the acronym LICADHO.

At the edge

Now 56 years old, Hak Lai could not afford to keep her children in school after she divorced her husband, who she said was having an affair. She and her five kids must make do without power or running water at their floating village home in Chnouk Tru, a fishing community near the southern shore of the Tonle Sap, Southeast Asia’s biggest lake.

Hak Lai’s oldest boy Hong, still just a teenager, was forced in 2013 to join the hundreds of thousands of Cambodian migrants in Malaysia, a country where an estimated 4-5 million foreigners, many of them from Bangladesh, Indonesia, Myanmar and Nepal, make up a huge chunk of the labour force.

But Hong, who had previously quit school to help his parents fish the vast lake, was soon sent back from Malaysia due to mental illness, adding to Lai’s swelling financial and emotional burdens.

“I quit fishing to look after my son, so at that time the house income depended only on my husband,” she said.

Money worries were compounded by the stress of caring for a stricken teenage son – taking their toll on a marriage already strained by infidelity. “About two years later, we got divorced and have lost all connections to each other,” Lai said of her estranged ex-husband. “And I have never received any of his support since then.”

The absence of at least a joint breadwinner has sent Lai into a debt spiral, taking on loan after loan from a local private lender. With a combination of drought and upriver dams on the Mekong reducing the level of water in the lake – as well as a temporary ban on fishing – Lai feels like she has no way to earn a living and nowhere left to turn.

“I could barely have enough to eat, let alone having money for my son to see psychiatrists in Siem Reap or Phnom Penh, so I decided not to continue paying for his treatment,” she exclaimed.

Hak Lai’s story is surely a painfully familiar one to many families across Cambodia. According to a recent LICADHO report on Cambodia’s microfinance sector, taking on loans forces poor families to put children out to work, with 13 of the 28 households interviewed saying they depended on such labour to make repayments.

Most of the children employed in the name of servicing debt were between the ages of 13 and 17, although LICADHO researchers heard cases of children as young as seven being required by parents to work on family farms to help meet debt obligations.

Sang Sokveng, a 46-year-old disabled father of four from the same village as Hak Lai, was forced, like many other single parents, to take some of his kids out of school, leaving just his second daughter in the classroom.

Usually a fisherman and handyman with a side-job selling firewood, Sokveng has had a desperate run of luck since losing an eye as a child – a misfortune compounded when one of his arms was maimed in a boating accident about two decades ago.

Now Sokveng is laid up with dengue, a debilitating mosquito-borne illness, leaving sister Sang Chan Houy to take up her brother’s story.

Similar to Hak Lai’s broken marriage, happy-ever-after proved just as elusive for Sokveng.

A year ago he and wife Eum divorced, Chan Houy explained, a rift that further diminished the family’s income.

“Veng’s wife, Eum, used to sell clams before she migrated to Malaysia due to the poor status of the family,” she said, a reminder that sometimes it is Cambodia’s mothers who are at least joint breadwinners.

“But she came back a year later with a boyfriend and left all the four children with the disabled Veng,” said Chan Houy, her voice shaking with anger at the sister-in-law’s infidelity.

Eum now works as a karaoke girl in Phnom Penh and has no contact with her ex-husband or children.

Even those humiliations were not the end for the stricken Sokveng’s ordeal. Moved by officials from a floating village house to one on land, albeit without power or clean water, the family’s woes were compounded by flooding that forced them to stay with Chan Houy.

“There are a few donations sent to the floating villagers, but it only lasts a short time,” sister Houy said, asked if the government provides any social welfare or financial support.

“Moreover, whether it’s free schooling or free health care service, it doesn’t ease my family income at all,” she added, ruefully wondering if there is any non-governmental organisation “that helps families in situations like this?”

Tough sell

LICADHO’s Sam Ath said that though such support is indeed there, it is insufficient in most cases. “There are NGOs which works on health service, but they cannot help all families,” he said.

“In worst cases, the female of the family has to force herself to find any possible job or even sell her hair.”

For families who can afford it, Cambodia’s burgeoning life insurance industry can help them weather the death of a loved one when times are desperate. A report released by the Insurance Association of Cambodia earlier this year showed that the Kingdom’s insurance industry had grown by almost 30% in total gross premium between 2017 and 2018, with 50.6% of that growth driven by life insurance. But knowledge of the ins-and-outs of insurance plans and premiums remains low among much of Cambodia’s rural population – even those who could afford to take out a policy.

38-year-old Sreymom* from Prey Veng, an agricultural province about 90km east of Phnom Penh, lost her mother and father when she was a teenager.

Despite having nine siblings, she recalled that the family did not have to stretch to make ends meet. “Life wasn’t as bad when I still had my parents,” she said. “My dad had worked at the bank and my mom had sold food in a primary school in Prey Veng.”

As the youngest, Sreymom, unlike the others, was forced to quit school early to look after her ageing parents, who died when she was 18. Their passing left her “nothing but an old house,” as she put it.

“Each family should think of a long term plan. Every member in the family should not rely only on one person”

Am Sam Ath, LICADHO

Finding work in Cambodia’s then-nascent garment sector, Sreymom first moved in with an aunt in Prey Veng, before eventually getting married at the age of 26 to a teacher from her hometown.

With her first child, a daughter, on the way in 2003, Sreymom quit her job, leaving her teacher husband to provide for the family. Tragedy soon struck, however, when her young daughter, her first born, died at just three years of age.

Nine years down the line, at a time when Sreymom was two months pregnant with a son, she divorced her husband – a schism she remains reluctant to discuss – and moved to Phnom Penh, setting up shop near Wat Phnom, a temple landmark in the capital known for its nighttime sex trade.

There Sreymom took a hefty loan, pointing across a streetside table to her lender as she spoke. “I borrowed $500 from this lady to buy a cart to sell drinks and now she came to collect the money,” she said.

To repay the loan, Sreymom ended up peddling more than just chilled bottles of iced tea and Coca-Cola. “For almost three years, I’ve been selling everything, both sex services and drinks,” she said.

Needing to find money not only to repay the loan, but to support her toddler son, the risk of arrest is one she felt she had to take at first. “The district police often conduct a raid around this street, that’s why now there are fewer and fewer girls,” she said. “Many girls got arrested and never came back. I’m afraid that if I might get arrested and no one would feed my son.”

In the end, Sreymom gave up sex work, due to a combination of having to run a capricious vice cop gauntlet as well as the worry that her son could end up stigmatised.

“But that’s not the only reason why I stopped,” she said, talking about the police raids. “My son is now almost three years old – I don’t want to shame his future by having a mother working as sex worker.”

Activists feel that there is more that the state can do to assist vulnerable and dependent families. For Soeung Saran of Sahmakum Teang Tnaut, better information about what assistance is available is needed. “There is very little knowledge about what support systems exist to help families like this,” he said.

LICADHO’s Sam Ath feels that a growing and productive economy can, in the end, make lives better for all and diminish the debt and migration traps that snare many hard-pressed families.

“The government has to increase more market on jobs, especially locally, and that would likely decrease migration rate in Cambodia,” he said.

All the same, the plight faced by Sreymom and others is a reminder that hard-pressed families need to come up with contingencies and plan ahead to pre-empt disaster or tragedy.

“I think each family should think of a long term plan. Every member in the family should not rely only on one person,” Sam Ath counselled. “Each and every one needs to get involved to build a family.”

The Ministry of Social Affairs did not respond to requests for comment.

*name changed to protect identity