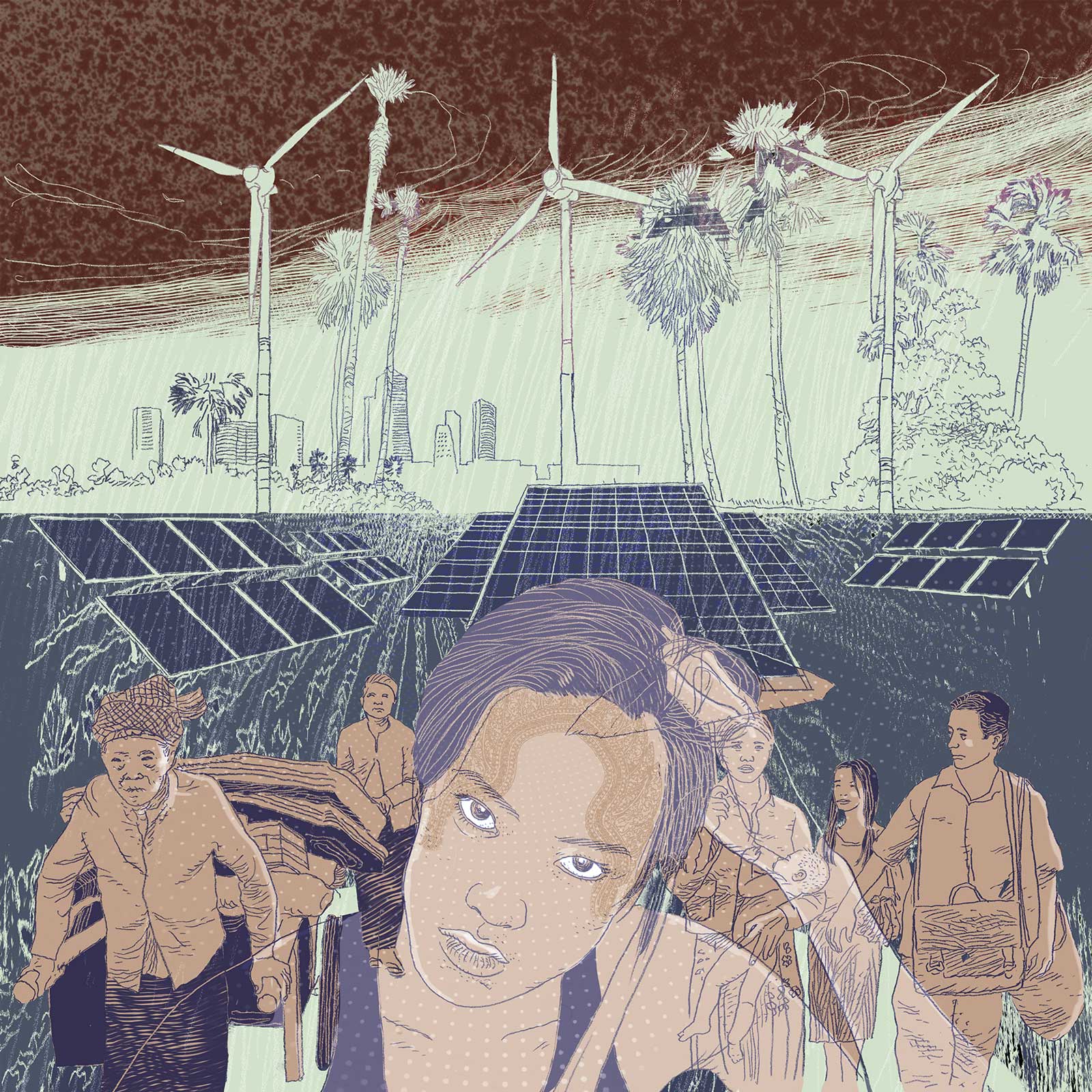

Illustration by Séra

Sothy was late.

For the first time in memory, he had slept through his alarm, rising and getting ready just in time to watch his usual 8am bus glide away from the stop.

But it was no matter. Sothy was actually happy as he wheeled his bicycle into the street and nosed it into the bike lane. The morning was beautiful and clear and as he sailed with the flow of other cyclists between pools of sunlight and the shade of street-side trees, he decided he should really do this more often.

The year is 2040. Sothy, a university lecturer, lives in a Phnom Penh that is at once familiar and deeply changed by the 20 years that lie between him and us. Unfortunately for Sothy, he’s also just a character in a book – a man of a greener, cleaner tomorrow imagined by the authors of Cambodia 2040, a collection of essays and research by Cambodian think tank Future Forum.

As Sothy pedals his bicycle, the rest of Phnom Penh is driving to work on the other side of the lane divider. He listens to the whirr of electric motorbikes and the deeper thrum of cars in the ride-share lane. Ever since the battery design boom of the 2020s, you just don’t see many gas or diesel cars on the road anymore. The city government had considered banning them at one point, Sothy heard, but the free market ended up doing most of the work for them.

After stopping for a quick breakfast – his favorite rice and banana cake, cooked by a street vendor on a compact, biogas burner and served in a simple banana leaf wrapper – Sothy arrived at university and made his way to his office, taking time to enjoy the walk. The never-ending, city-wide push to create more green spaces had reimagined the campus, and the singing of the birds above often made him feel that he’d walked out of the city and back into the forests of his youth.

Once a land of emerald, primordial forests, our present-day Cambodia on the cusp of 2020 has undergone a decades-long campaign of illegal deforestation that has denuded large swaths of country for timber and development. According to the United Nations Development Programme, in 1975, forests covered about 73% of the country’s land area. In 2018, forest coverage had shrunk back to just below 47%.

In fairness, Cambodia remains one of the best-forested countries in Asia, but the rate of the clearing has propelled it to the precarious status of being a nation with among the fastest deforestation levels on the planet. The pace of the clearing is even visible from space – as shown in 2017 satellite imagery published by US space agency NASA, which found that Cambodian deforestation accelerated between 2001-2014.

Opportunities in hardship

Will that trend hold until 2040? In Sothy’s world, it seems this unsustainable approach has been curbed.

Future Forum contributor Sam Art Chan sees opportunities in the challenge to reverse the destruction of Cambodia’s forests. He envisions a country in 2040 that has matured in the realm of soft power, a green Kingdom whose reach extends through aspirational influence in the promotion of biodiversity and natural resource management.

“I think in 2040, Cambodia could be a gold standard,” he said.

The country has set a reforestation goal of restoring 60% tree coverage by that year. It’s an ambitious goal, but one Sam Art thinks is within grasp provided Cambodians continue to approach it in good faith. For him, that means a robust system of environmental governance that prioritises the responsible use of natural resources.

Despite its wealth in such resources, Cambodia remains a developing nation challenged by poverty. A decade of strong economic growth has helped propel millions from the most-crushing depths of poverty, but the World Bank cites government data to report a poverty rate of 13.5% of the population as of 2014 – the most recently agreed upon data.

About 90% of the poorest live in the countryside with scant access to better economic prospects or basic amenities such as electricity or running water. Even for those who have escaped the official designation of poverty, roughly 4.5 million people are still classified as near-poor, and are vulnerable to backsliding when hit by even minor crises.

With that background, rampant environmental exploitation presents an opportunity for quick income at the cost of a chainsaw or a snare for wild game.

Sam Art says poverty reduction is still the main goal for the state, but he doesn’t see that as being mutually exclusive from conservation. Rather, he’s looking toward opportunities for Cambodians to grow with their environment – not against it.

“We need to make environmentalism more accountable, inclusive and performance-oriented,” he said.

To that, he points to what he sees as an opportunity to expand and improve upon the Kingdom’s existing programme for community forests, which are protected areas where extraction is allowed for local residents on a sustainable basis. This would involve bringing in new technologies such as blockchain – a linked recording system that allows information to be logged permanently, to provide structure for environmental auditing and tracking of illegal extraction.

He also sees the need for a frank conversation with private industry about building a more sustainable industry for legally harvested timber, as well as creating other avenues for Cambodians to make economic gains from the earth while respecting its natural systems.

But for any of this to work, he cautioned, it’ll require strong governance – a combination of informed policy, stringent enforcement and integration between the various levels of authority in Cambodia.

Climate change researcher Keithya Oung Ty, a fellow contributor to Future Forum, agrees with this point.

“We’re seeing a disconnect between central planning and local capacity,” he said, talking specifically about climate change adaptation. “Those [farming and building skills] are lacking on a subnational level.”

Climate change

Though Cambodia is rapidly urbanising, its rural people – dependent as most of them are on the cycles of weather to maintain their agrarian lifestyles – may find themselves most at risk to the hazards of climate change.

There’s always been uncertainty on the Mekong River’s floodplain, but as water levels have fallen, spurred on by drought and upstream damming, or risen unexpectedly in violent floods, rural communities will need to look to a more integrated system of communication with central government to cope with 2040’s climate challenges. After all, the UN declared in 2015 that water woes could make Cambodia the world’s ninth-most vulnerable nation for natural disasters due to climate change.

Researcher Oung Ty sees an injustice in that, and he’s not alone. Many of the most-vulnerable countries in the climate drama are responsible for little of the carbon emissions that threaten their national existence.

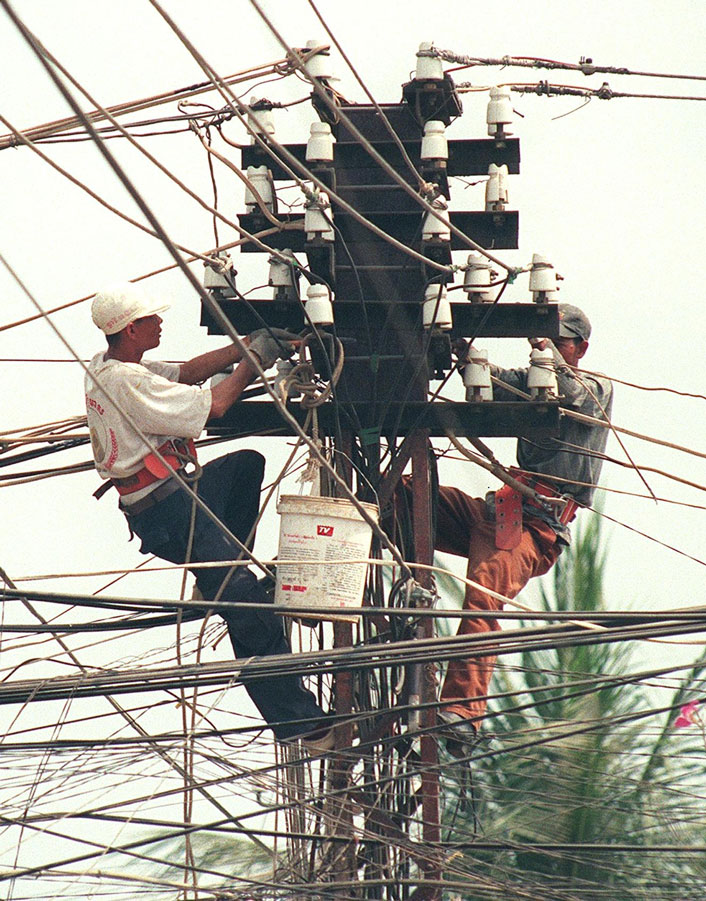

Maureen Boyle, an energy researcher from Curtin University in Australia, has studied how electricity flows across Cambodia. Her research presented a mixed bag of results, which she reported in a chapter for Future Forum along with Heng Pheakdey, an energy expert with Cambodia’s Enrich Institute.

“Energy use among people is quite low, especially in rural areas,” she said, adding that electricity access is poor among Cambodians today, especially in rural areas far from the national grid.

Though energy needs are still growing in the Kingdom, she said a lot of the demand is coming from industry – particularly the Phnom Penh construction sector and other booming city features like malls. But when industry is removed from the data, the picture changes.

“There’s actually space to allow more access to people,” she said. “There’s energy obesity on one side, especially on the construction [sector], and then on the other side, some people have maybe only two to three hours of electricity [per day].”

Sustainable energy production

These energy-poor Cambodians likely dwell far from the plugged-in yet energy-efficient reality of Sothy’s 2040 Phnom Penh, but without intervention, they’ll likely still have difficulties when that decade rolls around. Decentralised power systems, such as home solar panels or other gridless solutions, could pick up some of the slack, but Boyle doesn’t necessarily see a future in these systems as a fix-all for rural Cambodia.

Rather, she’s looking to a more sustainable and robust system of energy production, with a Cambodian network that leans heavily on wind and solar investment. As output from solar energy systems continue to improve each year, she’s seen government officials display a growing interest in reshaping sun-drenched Cambodia into a renewable power provider.

But part of the challenge of large-scale solar farms is finding space-efficient ways to install panels, especially in natural habitats or on agricultural land. Boyle and other solar advocates point to land-use strategies happening right now, such as using rooftops or floating arrays on bodies of water, as ways to maximise solar harvesting in the future.

About 90% of the poorest live in the countryside with scant access to better economic prospects or basic amenities such as electricity or running water

By 2040, Boyle hopes, the Kingdom will be a sparkling centerpiece in a regional energy market where Cambodia is positioned as an energy exporter to Laos, Thailand and Vietnam. Its central location between these countries could also prove useful as a main pillar in a regional grid that supports a shared energy market for Southeast Asia.

This enhanced regional cooperation might see a 2040 with reduced reliance on the hydroelectric dams currently harming vital river environments such as the Mekong. And should future-green powerhouses in Cambodia and elsewhere meet the demands of regional consumers, they could lead a phase-out of our current, carbon-heavy energy sources.

If the economic allure of renewables can’t do all the heavy lifting on its own, there might be another mechanism to nudge the market toward a less climate-damaging energy sources – carbon credits.

Both Oung Ty and Sam Art see potential in the ongoing carbon credits scheme – which sees companies pay fees to offset their carbon emissions by preserving habitat in developing nations – as a source of revenue for future Cambodians. By 2040, rural Cambodians could find themselves at the receiving end of a conservation economy with investment flowing in from those in more-developed nations who still use carbon fuels such as oil, gas and coal.

Sam Art is also advocating for investment directly for the people themselves in the form of skills training and environmental education, starting in the public school system and continuing into the workforce. Should that come to pass, the Cambodians of year 2040 could have an ecosystem that’s not only pristine, but also profitable.

While our friend Sothy from 2040 is an urbanite himself, his country’s embrace of biodiversity protection and climate-smart urbanisation regularly presents chances to get in touch with nature, even in the heart of the concrete jungle.

By now, in his greener future of 2040, he’s had a morning of pleasant surprises since missing his bus. As he settles into his desk on the fourth floor of his building, he hears the croaking of yet another.

A great hornbill bird has just landed on the branch outside his window. Sothy is glad to see her. Not only is the hornbill his favourite bird, this particular one is special, a regular visitor to the great kor ki tree outside ever since she’d nestled her chicks into a hollow.

The day had started with mishap. But, as Sothy gathered his lesson plan for his afternoon lecture on the Intro to Energy Futures course at his university, he knew things were looking up.

This article has been researched and written in partnership with Future Forum, in the lead up to Future Forum’s upcoming Cambodia 2040 book launch. Find out more here.