“Five children per family” was deputy prime minister Sar Kheng’s message to the Cambodian people recently as he urged citizens to make use of the country’s size by doubling the population.

For 63-year-old Yoeurb Yoeum, a large family is something he knows all about. The retired corn farmer and his wife look after their 12 grandchildren at their house on the outskirts of Cambodia’s northern town of Battambang. Most of their own children have left; caught up in full-time jobs, some of them only coming home once a year.

Life has been hard since Yoeum’s children moved away. In his household bustling with children, chickens and 13 new-born puppies, the thought of contributing to national prosperity by raising even more children is far from his mind.

“Once in a while, the children’s parents send us some money, but on some days we don’t have money for the kids’ teachers, so they would be absent from school for a few days,” he said.

His situation is common across Cambodia, said Ou Vanda, head of Cambodia Ageing Network, an organisation advocating for elderly support.

“In a small district we’re currently working on right now, out of 80 elderly, about 70% were left to look after their grandchildren,” she told Southeast Asia Globe over the phone.

“The belief that it is a child’s duty to take care of their ageing parents plays a big part in shaping the government’s elderly policy”

Tum Vira, executive director of HelpAge Cambodia

She warned that if the issue is not addressed, then there will be “a lot of problems” in the future.

Despite this, the government is doing little to tackle the impact of migration on the elderly, with scant mention of the issue in its 2017-2030 National Ageing Policy (NAP).

When contacted by Southeast Asia Globe, the government declined to give comment over phone or email, and a letter requesting an interview was rejected due to administrative reasons.

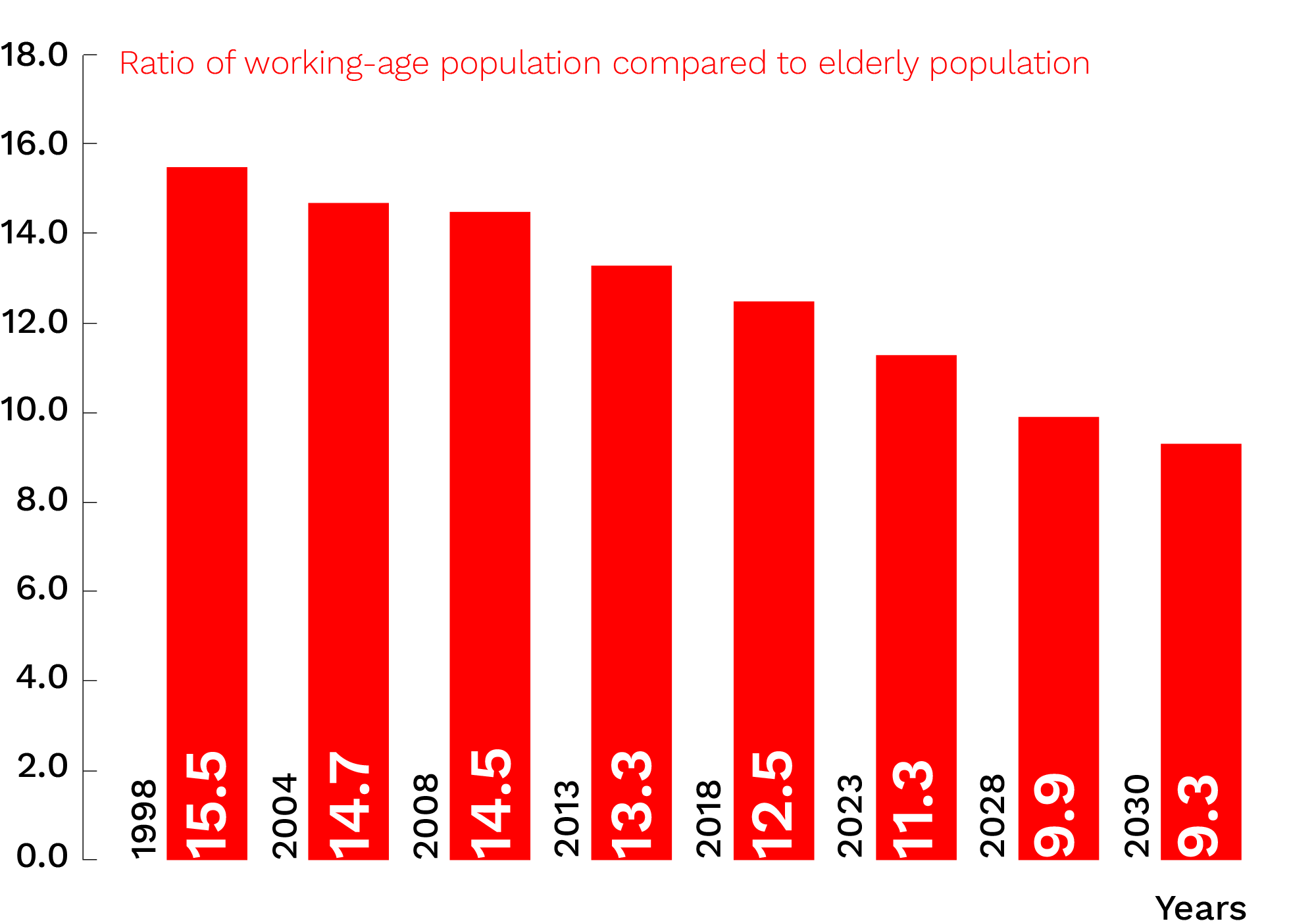

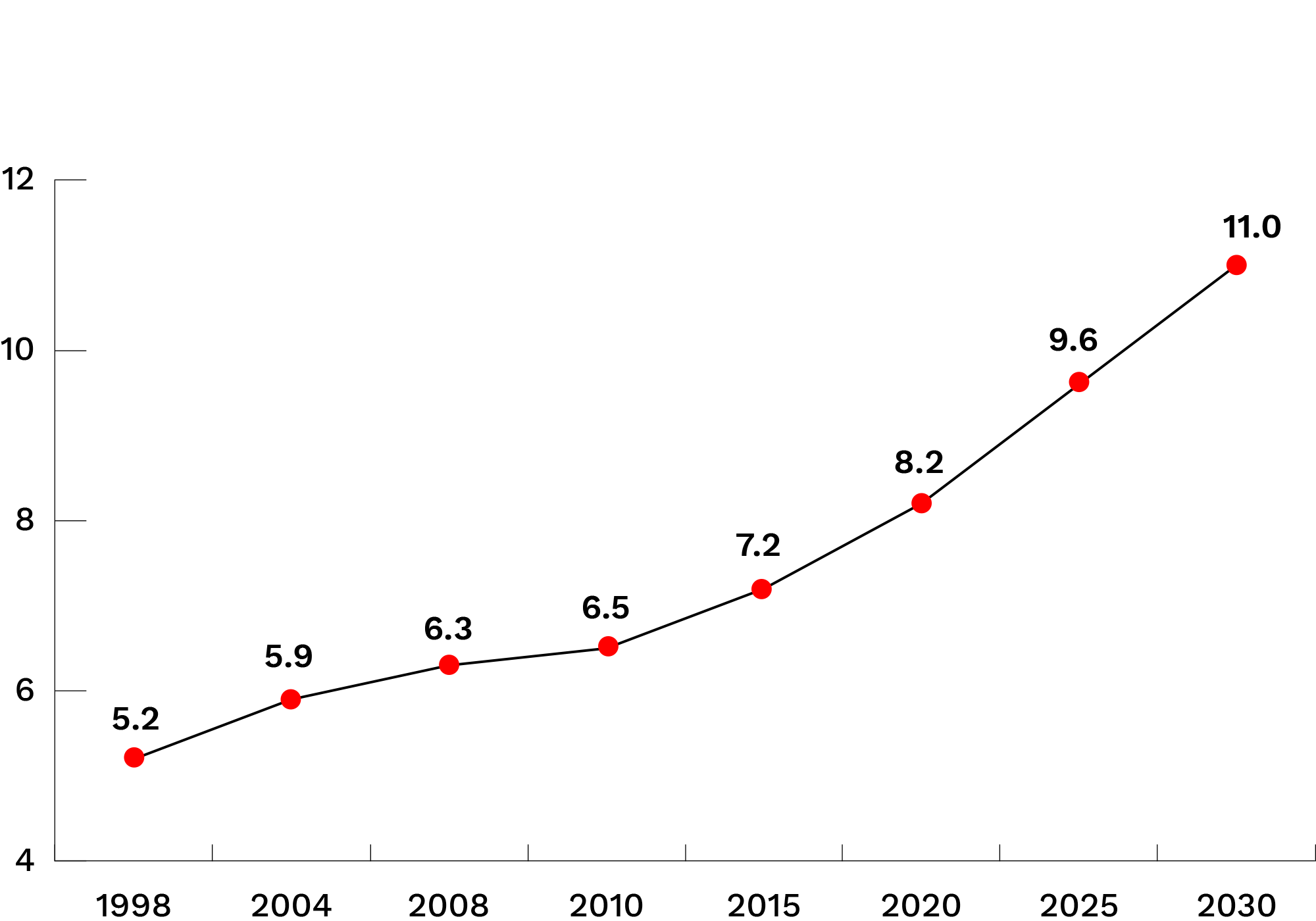

Shrinking of the family support base

Percentage of elderly population

Tum Vira, executive director of HelpAge Cambodia, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that contributed to the NAP, said that plans to tackle the effects of migration are still very “blurry”.

HelpAge is the only NGO in Cambodia that works with the government specifically on elderly care. Vira said such a dearth of voices could be one reason why less priority is given to the sector.

Another reason, though, is tradition. The belief that it is a child’s duty to take care of their ageing parents plays a big part in shaping the government’s elderly policy, Vira said. One of the NAP’s stated objectives is to strengthen the country’s family care system, which it describes as a “hallmark of Khmer culture”.

“The government relies on that,” Vira said. “When you advocate with the government, they put this responsibility on the children, but that is not the reality.”

Challenges on the ground

It is not Yoeum’s reality, and nor did he ever expect it to be.

When Southeast Asia Globe visited his family, the former farmer said that with so many grandchildren he knew he wouldn’t have a peaceful retirement.

He gave up working a few years ago to come home and take care of the grandchildren. Of his six children, two work in nearby Battambang, while three have joined the vast exodus of Cambodian emigrants to Thailand, a much more prosperous economy where migrants working on construction sites – as Youem’s children do – can earn up to $5 more per day for their labour. One daughter, Dy, recently quit her job in Thailand and has moved home to help her parents look after the children, six of whom are hers.

Looking after the children is difficult, Yoeum said, but he doesn’t complain. He points to a small, rickety wooden cart sitting idle in the dirt. On school days, he says, he loads all 12 children onto the back, hitches it to his motorbike and hauls them to their classes. His gnarled finger drops to his leg, tracing a 10cm-long pink scar.

One morning, the overloaded cart flipped over, trapping the old man under the motorbike’s poker-hot exhaust, the burn searing the scar into his leg. But he shrugs off the wound: the children weren’t hurt, and that was the main thing.

“I don’t know what will happen to my grandchildren if I fall ill”

Ort Bo, grandmother

Chhoem Ornt lives just a 15-minute drive north of Yeoum. Another surrogate parent, the 53-year-old is taking care of two nephews and her niece while her siblings work in Banteay Meanchey, a province bordering Thailand to the north of Battambang, as well as across the border.

“The main and only challenge is financial,” she said. Every month brings the anxious wait for the roughly $75 her brother and sister send home to feed, clothe and educate the three children.

Sometimes, like this month, the money comes late. And with the eldest nephew hospitalised with dengue as the Kingdom endures an epidemic of the mosquito-borne disease, the added medical fees mean Ornt is hard-pressed to make ends meet.

Throughout this stretch of verdant countryside close to the border, stories like these do not take long to find; widespread migration has impacted Cambodia’s young and old alike.

At 61, 12 years younger than her husband, Ort Bo takes on most of the workload caring for two grandchildren. One child is her son’s, who she has not seen for several years since he eloped with a new girlfriend. The other is new to the household. Bo’s daughter dropped the newborn off just two days before Southeast Asia Globe’s visit before returning almost immediately to work in the border town of Poipet around 100km away.

Two decades ago, when Bo was in her forties, Bo had a heart attack and has suffered with high blood pressure ever since. She is worried about what will happen to her grandchildren if her health worsens and would like government support, but says she doesn’t know how to get it.

“I just want a little support for my health because I don’t know what will happen to my grandchildren if I fall ill,” Bo said. “I want to give them education while I still can.”

Bo, though, is not unhappy with taking care of the children. She said that she likes the responsibility.

Far from unusual, this feeling runs contrary to the oft-repeated belief that Cambodia’s ageing population are being “left behind” by their children.

A 2017 paper titled Mother, grandmother, migrant: Elder translocality and the renegotiation of household roles in Cambodia dispelled this myth, showing the opposite was true.

Older people “are not vulnerable victims, but active agents in economic processes,” Dr Laurie Parsons, co-author of the paper, told Southeast Asia Globe via email.

Dr Sabina Lawreniuk, the other co-author, agreed, but stated that it didn’t mean the practice was entirely positive.

“For many of the grandmothers (and grandfathers) we spoke to, looking after their grandchildren full-time was not necessarily an easy task, even if they were happy to do it or at least derive some benefit from it,” she said.

The missing elements

What links the families that Southeast Asia Globe spoke to is that the working family members were all engaged in informal jobs. According to a 2018 International Labour Organisation report, a staggering 93.1 percent of Cambodia’s working population make their living in the informal economy.

“Lack of support for people in this sector is one of the main issues affecting the elderly in Cambodia”, Vira from HelpAge said.

“What support does the cyclo man have? What support does the government provide?” he asked, referring to Cambodia’s once-ubiquitous rickshaw operators, usually men pedalling around towns and cities, passengers in tow in a cart attached to an often-rickety bicycle.

For the most part such work is very much informal. Not only does the cyclo man not get anything like a steady salary, he mostly exists outside of the government’s already-thin social support system.

For some young people coming from families where migration is a few generations old, there is a “kind of mythical draw to working abroad”

Cambodian migration expert Maryann Bylander

As part of its campaigning ahead of 2013 parliamentary elections, the main opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) proposed a $10 per month pension for the country’s over-60s.

Perhaps the idea resonated: the CNRP came close to what would have been a surprise win over long-ruling Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party. But after a similarly close call in 2017’s local elections, the CPP and its allies in the police and judiciary set to work dismantling the CNRP ahead of the 2018 national elections – which were then won at a predictable canter by the virtually unopposed CPP.

In between, in 2015, Hun Sen mocked the CNRP’s social spending ideas, saying that the party “would collapse after six months” if it tried to introduce pensions and raise wages for civil servants.

Vira said that a state pension would be helpful for many elderly in Cambodia, adding that HelpAge Cambodia had advised including such a system in the NAP. He is not sure why it did not make it into the final cut.

He also believes the NAP should have featured healthcare outreach programmes targeted at the elderly. The government already encourages people to visit local health centres, but Vira said that these efforts are mostly aimed at younger generations.

Older people, Vira said, are unlikely to go to the doctor “if they don’t have serious symptoms”, in turn undermining early detection of cancer and diabetes.

W. Nathan Green, a geography lecturer at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, believes that the lack of access to healthcare for Cambodia’s elderly has bigger consequences.

“Most financial hardships in Cambodia can be traced to the precarious health conditions of the elderly,” said Green, co-author of Precarious Debt: Microfinance Subjects and Intergenerational Dependency in Cambodia.

Green’s paper documents how debt and distant labour markets affect a single Cambodian household. One interviewee, identified as Sothy, describes the current situation in Cambodia as “the era of the grandmother”.

“When I was growing up, parents almost always looked after their own children,” the paper reports Sothy as saying. “But not anymore. Now all of the youth have left the village to work in the factories and in other countries because everyone is up to their necks in debt.”

The path of migration

The indebtedness that Sothy mentions is one of the main causes of migration in rural Cambodia.

Microfinance institutions are a common sight in the Cambodian countryside, with many families taking out regular loans to pay for medical treatment, shore up their family business or, worryingly, to service other outstanding debts. But according to a paper by researcher and Cambodian migration expert Maryann Bylander, microfinance loans are also driving increased migration as families take out loans specifically to allow some members to move abroad for work.

“In my work, one of the biggest drivers [of migration] in some of the communities that I’ve spent time in is debt,” Bylander said.

But there are also a lot of factors that combine with debt to contribute to migration out of rural areas, Bylander said. She told Southeast Asia Globe that changing livelihoods, fluctuating agricultural commodity prices and environmental issues are all reasons why people choose to move out of their villages to seek higher-paid work elsewhere.

And, in some areas where migration is most common in Cambodia, such as Battambang, Siem Reap and Banteay Meanchey, there are added social drivers. She said that for some young people coming from families where migration is a few generations old, there is a “kind of mythical draw to working abroad”.

“It is a way that you can support your family, a way that you can prove you’re a supportive child… kind of a rite of passage,” she said.

While Cambodia’s economy has grown at an average of 7.7 percent a year since 1995 and GDP per capita has jumped from $785 in 2010 to $1205 in 2018, most of the jobs are in the cities – in garment factories and construction – and those numbers bear little relation to real incomes for migration-hit rural areas.

Vanda, the head of the Cambodia Ageing Network, believes the best solution to this is to create more jobs inside the country, near the home and to “avoid migration”.

In the meantime, she thinks Old People Associations (OPAs) could serve as a means to support the elderly and their grandchildren.

A photo for posterity

The Cambodia Ageing Network is a group made up of members of OPAs. These independently run groups have existed for a long time in Cambodia, but in 1998, HelpAge began formalising them as a way of supporting local elderly people. They offer help with food rations, provide small loans, meet to discuss community events, and generally offer a helping hand to older members of the community.

From the government’s perspective, these associations are both efficient and effective. Since last year, the state has rolled out over 1,600 OPAs at the local commune level.

While Vira appreciates the effort made by officials, he said that working at such a breakneck speed means that sometimes the “quality is not there.”

He said that when HelpAge first started to formalise these OPAs, they would spend one month speaking to members of the community. The government OPAs were set up in just one day.

But Vira said that if they are well established, then OPAs can be essential – “not just for old people, but for the community also.”

What the OPAs cannot do is bring back a generation of rural Cambodians that have left home.

After the interview was finished, Yoeum gathered everyone around for a photo. This proved no easy task – children darted in from almost every direction, and for a few minutes there was chaos around the house before everyone found a place.

But when the camera flashed, it caught only the old and the very young: the generation between – Yoeum’s grown-up children – are nowhere to be seen in the photo. In this absence, we see the plight of Cambodia’s rural elderly.

*Southeast Asia Globe’s visits to the families were organised by HelpAge Cambodia

Correction: an earlier version of this article stated the Cambodian government had rolled out over 1,600 OPAs since 2008. In fact, the rollout only began in 2018, although the government has been in talks with HelpAge since 2008.