Standing at the threshold of her bleached wooden shack, Heng Hong is preparing her evening meal. Faded blue petals tumble across her pyjamas, echoing the paler shade encroaching at the edges of her irises. Along the dry dirt road in Cambodia’s Kampong Speu province, a line of fraying eucalyptus cast white shadows against the sky.

Despite the dinner bubbling on the stove and the faded paintings plastered to the walls, though, this is not Hong’s home. Her home was lost almost a decade ago, when the banks came to collect.

“About ten years ago, I put down the land title to my house at ACLEDA Bank,” she told Southeast Asia Globe. “For Sathapana Bank, I had my neighbours take the loan in my stead, the ones who weren’t in any debt. I borrowed their land titles to take a loan at Sathapana.”

Living on the outskirts of Kampong Speu’s Kong Pisei district, Heng Hong is one of many Cambodians who have had to sell off her land to service microloan debt. Photo: Paul Millar

All up, Hong borrowed almost $3,000 from different financial institutions. The first payment went towards a motorised tuk-tuk for her husband. The second, she took out when he accidentally struck a pedestrian, settling the matter with borrowed cash before it turned ugly. The third, when her nephew begged her to help fund his installation business in Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, proved too much for her to repay.

“My former neighbours didn’t want me to sell the house, but I didn’t have a choice,” she said. “I had no way to pay back the loan. For ACLEDA I only had to pay three more months, but the staff there complained that I was always late. It was true, but I was still hurt by that.”

Her nephew’s mother has since died, and with her the last link between Hong and the man who drove her back into debt.

“We’ve lost contact with each other since my sister died,” she said. “Now he still owes me hundreds of dollars, but I can’t afford to go to Phnom Penh and ask for the money.”

Blind in one eye, her face is still swollen from a moto accident that shattered her wrist and pulled her cheekbones out of place. At her feet, her grandchildren tear apart packets of uncooked instant noodles, the dry food splintering between their teeth.

“I don’t have any land titles anymore,” she said. “This land I’m living on, I don’t have the rights – but I asked permission to live on land from the local monks, the village chief and the district chief.”

Hong is far from the only Cambodian to have been ruined by debt. A new report on Cambodia’s microfinance industry released by human rights group LICADHO and local land rights organisation Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT) details what it describes as systematic land loss and human rights abuses as indebted farmers are forced to sell off their property at a fraction of its value after defaulting on their loans.

Detailing the activities of the nine largest microfinance institutions (MFIs) operating in Cambodia including ACLEDA, Sathapana Bank and PRASAC, the report accuses the industry of forcing poor Cambodians into debt bondage, forced land loss, homelessness, child labour and malnutrition.

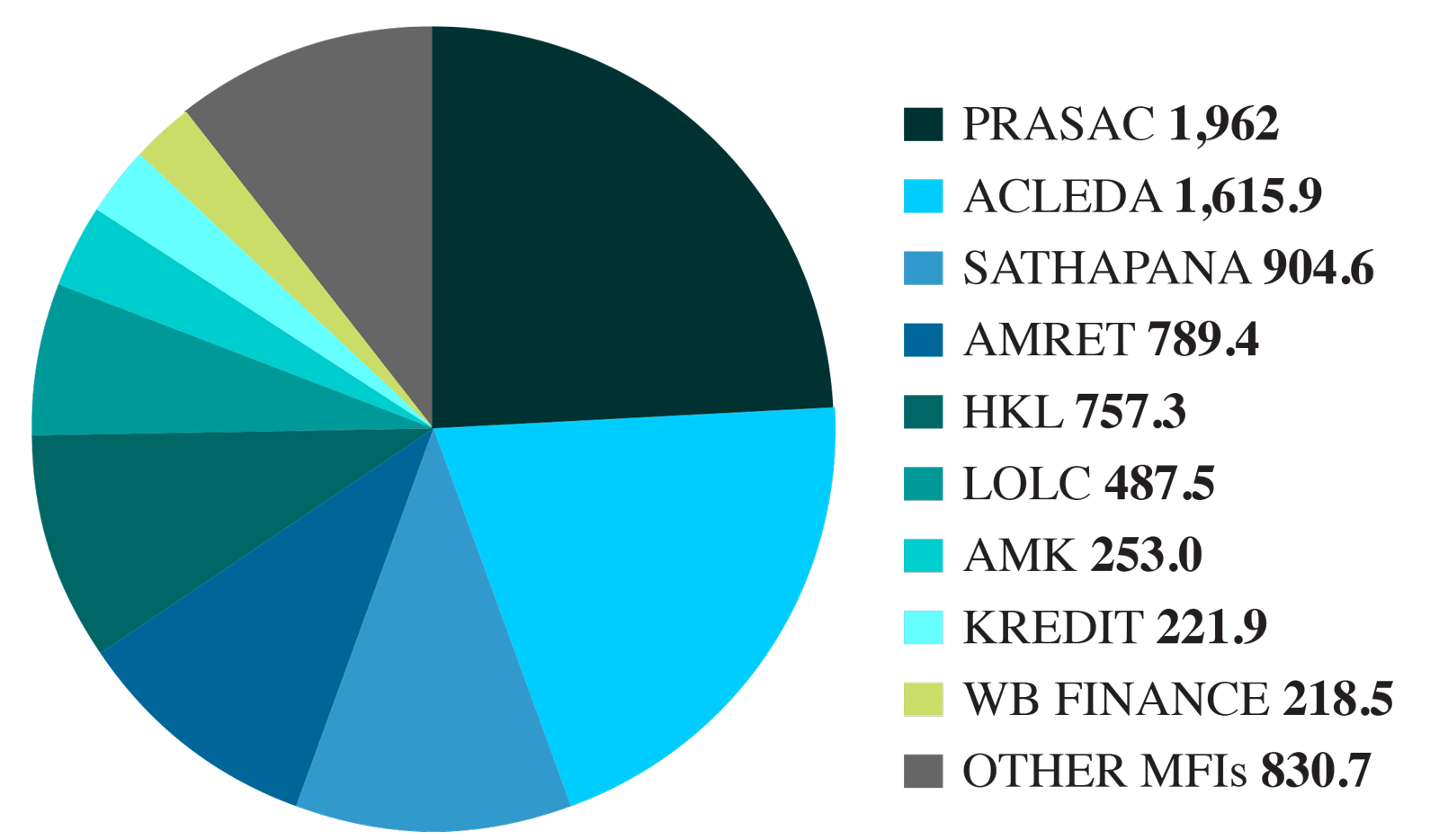

Cambodia’s MFIs by largest loan portfolios

(in millions of USD)

For many Cambodians across the Kingdom, debt has become an essential part of life. The report claims that at the beginning of the year, roughly 2.4 million Cambodians held a grand total of more than $8 billion in outstanding microloans – a staggering one-third of the nation’s entire GDP. The average debt size, more than $3,000, is the highest in the world. Factoring in the informal sector of private lenders, the true weight of unpaid debts in the Kingdom is likely much higher.

But the sheer number of Cambodians taking out loans to support themselves is just the beginning. The report paints a damning picture of a profit-hungry industry preying upon households unable to pay back the money they’ve borrowed – and strong-arming them into selling their land when they finally default.

“Land prices are the single most important factor for the MFI market right now”

Anonymous MFI executive

“Over the course of three weeks of field work, researchers interviewed 28 households whose members had suffered multiple and/or serious human rights abuses as a result of MFI debt,” the report stated. “Of these 28 households, 22 had experienced a coercive land sale; 13 had engaged in child labour; 18 had a family member migrate due to debt; and 26 had eaten less or lower quality food in order to make loan payments.”

Much of the problem lies in the fact that much of the debt taken on by Cambodian families – overwhelmingly the nation’s rural poor – is lent against their land titles, which are held by MFIs as collateral. The land in question – usually fertile fields that are the livelihood of many Cambodians living in the provinces – often far exceeds the size of the loan in value, a fact that doesn’t deter many MFIs from requiring multiple land titles in return for a loan.

Land grabs are nothing new to Cambodia, with clashes between local communities and large corporations granted sweeping agricultural concessions a source of tension and even violence as security forces push protesters off the land they refuse to leave. But unlike forced evictions carried out with naked brute force, some Cambodians who take out loans are left with little choice but to sell off their own properties – or risk being dragged before the courts.

At the beginning of 2019, roughly 2.4 million Cambodians held a grand total of more than $8 billion in outstanding microloans. Photo: Nicolas Axelrod / SEA Globe

And as land prices continue to climb, the problem will only get worse.

“Land prices are the single most important factor for the MFI market right now,” one MFI executive told researchers.

Ouch Sidoum, chief of Khrang Khnorng village in Kampong Speu’s Kong Pisei district, knows only too well what it’s like to live in debt. Wearing just black exercise shorts and a black-and-gold scarf knotted around his waist, his pen stabs at the wooden table with each word, ticking boxes only he can see. Across his chest, arching Khmer script sits softly just beneath his skin.

There are 1,040 people in his village, he tells us, and more than 65% of them have taken out loans from MFIs. Of that number, three quarters had been from ACLEDA – one of two major microfinance institutions that have set up shop in the rural town.

“If someone takes out a loan and can’t repay, the company comes to me and I talk to them,” he said. “I have the companies postpone the deadline.”

The companies in question are not always as understanding. The report alleges widespread accounts of coercion on behalf of increasingly ruthless MFI officers, who use the land titles as leverage to pressure debtors to sell their precious property at a fraction of its market value. More troublingly, the report claims that in a number of instances local village- and commune-level authorities – men much like Sidoum – use their position to act as enforcers on behalf of the companies. These standover tactics were corroborated by two MFI executives who spoke to the researchers on condition of anonymity.

“In one case, a village chief from a neighbouring village offered an MFI client a private loan in exchange for two land titles, and then sold her land titles and forged her thumbprint without her consent when she was unable to repay her debt,” the report stated. “In another case, a villager reported that the commune chief had called in other MFI borrowers who were late on their payments, and she was so afraid of being summonsed that she sold her land in order to avoid a late payment.”

“The average wage in Cambodia is still limited. If their house needs urgent repair or somebody in the family fell sick, there’s no way we can find that much money in such a short period.”

Village chief Ouch Simoun

Despite acting as middlemen to verify land titles for new loans, these officials are not free from the debt cycle themselves. Eight years before becoming the village chief, Sidoum took out a $10,000 loan from ACLEDA. Now, he is $20,000 in debt. Every month, he pays back $570 to keep his creditors at bay.

“It would be such an embarrassment as a leader to have my house sold in order to pay back the loan,” he said. “Before, I had my children’s support, but now they are all married.”

This, too, has been a common solution to the mounting debt that many Cambodian families find themselves in. Unable to earn enough to pay down their debt and unwilling to sell the land they need to survive, many families pull their children from school and set them to work in the Kingdom’s fields or garment factories. Others send them abroad, hoping they can earn enough on the decks of a Thai fishing boat or labouring in the belly of a building site to pay off their parents’ loans.

“My youngest daughter left school in grade nine,” Sidoum said. “She was afraid of people, and she couldn’t stand going to school, so I decided to let her stop and work as a garment worker. But she couldn’t earn enough to support the family – she’s still afraid of people. Often, she can’t go to work.”

Despite sharing multiple horror stories of families forced to sell everything to pay off their debts, Sidoum said that most people in his village were grateful to have the MFIs – an indication of how strapped many Cambodians are for cash, and of the lack of anything like a social safety net for the country’s poorest.

“The average wage in Cambodia is still limited,” he said. “If their house needs urgent repair, or a child is marrying, or somebody in the family fell sick, there’s no way we can find that much money in such a short period.”

“Cambodians should not require predatory loans to access basic services which are supposed to be provided by the government, such as healthcare”

LICADHO director Naly Pilorge

Sokha, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, is no exception. The ageing widow described how she turned to MFIs to cover the costs of the crises that had hit her family.

“My husband died when my youngest daughter was seven,” she said. “He was a soldier. Around eight years ago, he was wounded in an explosion after another soldier stepped on a buried bomb.”

The shrapnel stayed in his body for years. When it finally killed him, she said, the lieutenant responsible for ensuring his family was compensated for his years of service took the money and left. They never heard from him again.

Instead, Sokha was one of the many villagers Southeast Asia Globe spoke to who had witnessed a fleet of microfinance officers sweeping across the countryside in search of fresh clients. Facing their own monthly lending quotas and pressure from their superiors to ensure the debts are paid, these young men and women have been accused of encouraging clients to take out fresh loans from third parties rather than default on their existing loans, dooming them to an ever-deepening cycle of debt.

In response to the report, Cambodia Microfinance Association (CMA) chairman Kea Borann slammed the study as unrepresentative of the industry as a whole.

“The CMA takes very seriously any reports of unethical or predatory lending practices and we will work with our members to investigate the case studies presented in the report,” he said.

“Microfinance has been an integral part of Cambodia’s economic growth and has contributed to a reduction in poverty levels from 47% of the population in 2007 to 13.5% of the population in 2014 according to World Bank data.”

“A year ago I got into an accident and broke my right arm.They told me to come back to the hospital to fix the fracture but I can’t go. If I go to Phnom Penh, there will be no income for a day”

Heng Hong

The report listed ten instances of loan officers signing up new clients despite having every reason to believe that their targets lacked a stable livelihood to repay – or worse, had already been forced to take out informal loans to pay off their first MFI debt.

So when her daughter fell sick, leaving Sokha with no option but to take out a loan to pay for her treatment, she knew exactly who to speak to. Despite driving herself into debt to pay the clinic, the doctors could only do so much. Now, her daughter remains in the care of the monks who live at the foot of the mountain, praying over her every day for her recovery.

As macabre as it may sound, Sokha is one of the lucky ones. With four daughters working in the windowless garment factories that line Kampong Speu’s highways and two sons-in-law driving tuk-tuks for a living, she has always been able to pay back the money she has borrowed.

Hong has had no such fortune.

“One of my boys has been in jail for drugs charges for more than a year – within eight months he will be out,” she said. “Before he was imprisoned, he was a labourer. His wife is a garment worker. I used to receive some support from them but after he got charged, they got divorced. I hardly ever visit him because I don’t have the money to do so. Ever since he’s got charged, I’ve only visited him twice.”

Like many working-age women in the district, two of her daughters work in a garment factory. The third is eight months pregnant.

“They say the baby has a big head and that she needs surgery in order for her to give birth,” she said. “But we can’t afford the surgery. Another one of my daughters gave birth to a premature baby a month ago. It died just four hours after birth. We buried it in the yard.”

It’s a precarious life. Stripped of her land title, she can no longer borrow the money she needs to support her and her family.

“A year ago I got into an accident and broke my right arm,” she said. “I went to Preah Kossamak Hospital in Phnom Penh, who treated me for free. They told me to come back to the hospital to fix the fracture but I can’t go. If I go to Phnom Penh, there will be no income for a day.”

With the Kingdom lacking any real healthcare or social safety net to speak of, Cambodians are becoming increasingly reliant on MFIs and private insurance companies to keep them afloat in times of crisis. LICADHO director Naly Pilorge, said that Cambodians should not have to risk bankruptcy just to survive.

“We are not calling for MFIs to stop lending money, we are calling for them to stop abusing human rights and engaging in unethical practices,” she said. “Cambodians should not require predatory loans to access basic services which are supposed to be provided by the government, such as healthcare. In other countries with microfinance sectors, other forms of collateral are used for microfinance loans that go toward business operations. The effect of not requiring land titles as collateral would be that borrowers feel less pressure to sell their land in order to resolve their debt.”

Instead, the report calls for international development agencies who have ploughed billions into funding developing nations’ microfinance sectors to invest in community-led financial programmes less driven by the bottom line.

“We recommend a system that provides access to capital but does not seek to indebt people in an unsustainable way or require vulnerable borrowers to lose their land and suffer from human rights abuses,” Pilorge said. “If no action is taken, we expect more human rights abuses to occur at a faster rate. We call on the government, MFIs and their international development partners to take immediate steps to protect and provide relief for Cambodian borrowers.”