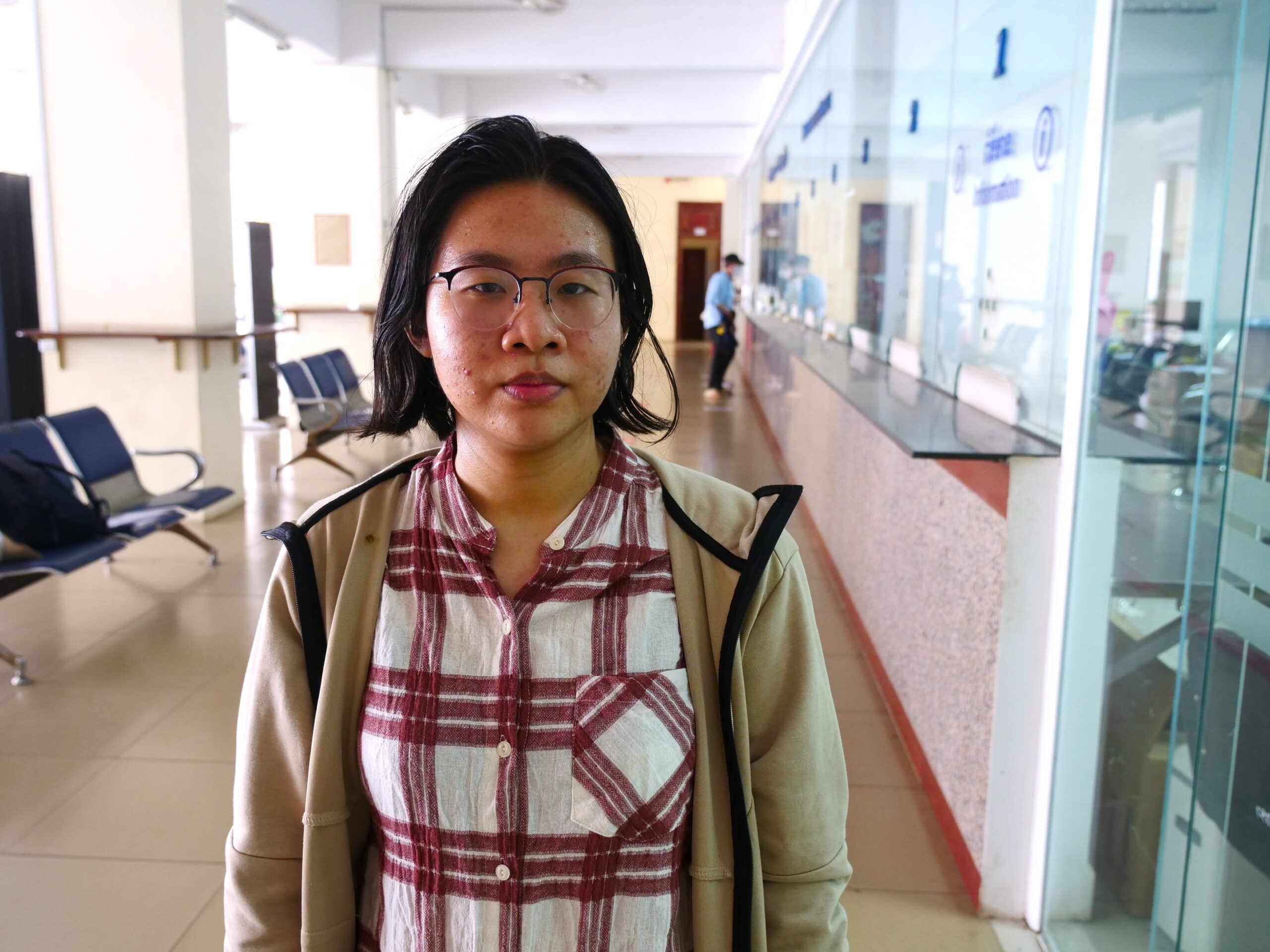

After picking up her graduation certificate from Cambodia’s University of Health Sciences in mid-October, 24-year-old Soth Yanuth is now able to begin work in healthcare following six years of study.

“I think I could get experience from the public [sector] better than in private,” she said.

Yet Yanuth’s future salary as a civil servant is likely insufficient to cover the costs of living in Phnom Penh, based on WHO figures and other studies. One option she and other health civil servants have is to supplement their income with additional work at private clinics, which is known as “dual practice.”

“In public [hospitals], there’s a lot of shifts between doctors and in one shift there’s a lot of doctors,” Yanuth said. “So they could spare some time in the private clinic.”

With the minimum wage for healthcare civil servants estimated well below $300 as of 2018, doctors and specialists can add between $50 and $350 to their incomes per month through dual practice, the WHO reported. Prime Minister Hun Sen has promised to continue raising wages for civil servants.

Despite its legality in Cambodia and ubiquity in the medical profession, a 2020 Transparency International report found most Cambodians in an accompanying survey wanted government-employed healthcare professionals to work solely in the public sector. A majority of respondents said they saw corruption in the actions of doctors who send public hospital patients to private clinics or operate clinics during hours overlapping with their public sector work.

While not illegal in Cambodia, dual practice can be a source of absenteeism and conflict of interest. Charity hospitals often prohibit staff from taking private practice work.

In 2016, the Cambodian Ministry of Health estimated there were 6,550 physicians working in the Kingdom, with 4,500, or 68%, believed to be in private practice. Yet 4,979 physicians were registered with the Medical Council of Cambodia as public-sector doctors. The statistical crossover appeared to show many physicians were double-dipping.

Heath Iyheang, a recent pharmacy school graduate who works at a private pharmaceutical company where employees earn between $300 and $400 per month, said she would not split her time between more than one workplace.

“I think it’s not really good because sometimes we cannot focus on the work we are doing, if we have to work two places at the same time,” she said. “We cannot focus.”

Yet University of Health Sciences (UHS) medical student You Dalin recalls that many doctors at the Khmer Soviet public hospital, where he interned, also had part-time gigs in private clinics.

“They have to work in the public hospital first,” the sixth-year student said. “Then they go to [private] work part-time.”

Dual practice can offset the steep investment of time and financial resources for aspiring medical practitioners. UHS charges an annual tuition of $1,500, while many students also pay for French and English classes to understand lessons that are generally not taught in Khmer.

Nearly every country in the world has some form of dual practice

The Transparency International report also found public survey respondents considered offers of extra cash in the hope they will receive better service to be the most common form of healthcare corruption. However, the majority of those who admitted to providing the so-called “tea money” said the payments were made without direct solicitation from healthcare professionals.

“In Khmer culture, we normally try to give back,” said Im Norin, director of programmes at Transparency International. “If someone helps you or anything, you need to compensate it.”

The practice of side payments, also known as ‘tea money,’ has alienated some would-be patients, such as Phnom Penh resident Leaphea Yong, who said she goes to private clinics to avoid hassles and ensure quality care.

“Sometimes I hear at public hospitals if you don’t give them tea money they won’t give you medicine and they are rude,” she said. “I prefer private hospitals because they are more modern and have good service.”

While tea money and dual practice are separate issues, both are linked to low pay for public sector healthcare workers due to government budget constraints, according to Dr Peter Annear, a University of Melbourne professor of global health who has studied the Kingdom’s health systems. Most doctors engaged in dual practice act ethically and provide basic financial support for their families, he said.

“Cambodia is in no way unique,” Annear said. “Nearly every country in the world has some form of dual practice and some form of extra payments by the patients for healthcare.”

Dual practice should not be seen as inherently corrupt and, in some ways, is a benefit to the public, according to Annear.

“If dual practice were banned, it would probably mean a lot of doctors simply have to leave the government service and work in the private sector,” he said. “[Cambodia] might be in an even worse position where the public sector is weakened by that, not strengthened.”

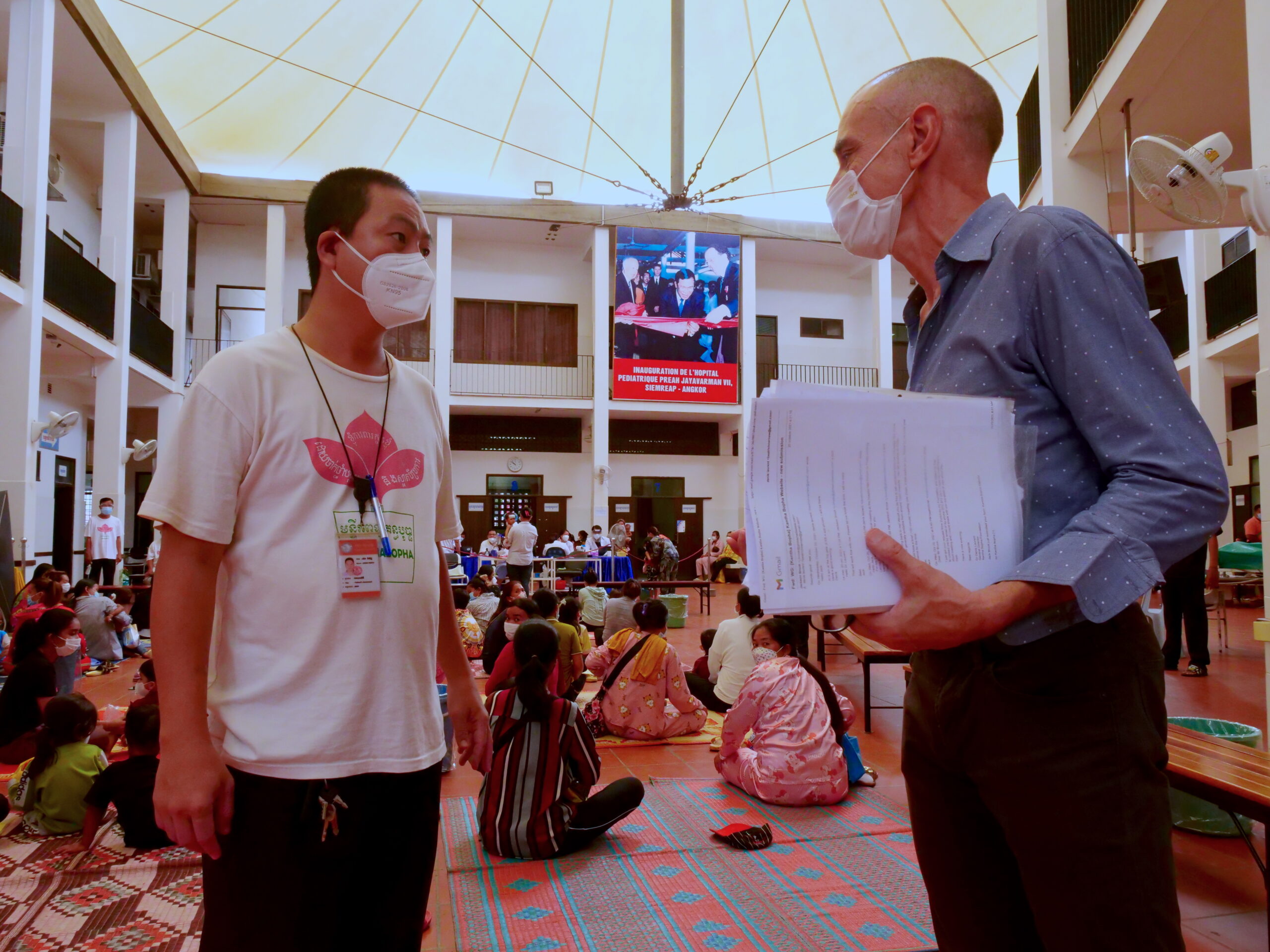

Still, employees need to be motivated to treat patients without discrimination, said Dr Denis Laurent, general director of the Kantha Bopha Foundation in Switzerland, which has provided free treatment at its Cambodia-based hospitals since 1992. Kantha Bopha doctors make around $1,600 monthly and nurses are paid $600 to $700 but cannot engage in private practice, he said.

“Salary is important because you have to live and without money you cannot,” Laurent said. “But also it’s important to motivate people.”

Doctors receiving adequate wages provide a better quality of care without bias, Laurent argued, noting that when Kantha Bopha opened a maternity clinic in Siem Reap in 2001, the rates for cesarean section operations were significantly lower than in other hospitals. He believes the employees had no incentive to initiate costly procedures when they were not medically required.

Public hospitals typically cannot afford to pay employees the same rates as Kantha Bopha. Yet Laurent contends his employees’ salaries are not high, but merely “correct,” allowing them to concentrate on their long, six-day work weeks, which include 24-hour shifts every four days.

“If you work for Kantha Bopha you have to work 100% because the conditions to work are not so easy,” Laurent said. “So it’s a lot of energy.”

Acknowledging the importance the public sector has in sustaining private practices, Annear suggests Cambodia should find ways to regulate dual practice using both carrots and sticks. Doctors known to be non-compliant with practice regulations could be given a poor public rating or “de-recognised” by the government, he said.

“We know that doctors and nurses in Cambodia feel, very much, that being a government employee gives them prestige as a medical practitioner,” Annear said. “It’s an endorsement, and it verifies their training and their experience and their skill, that they have that role. And then that prestige helps them, of course, in their private practice.”

He points out how Cambodia’s healthcare system has come a long way since 1980, when there were few medical doctors left in the country following the Khmer Rouge regime. As Cambodia emerged from decades of conflict, the World Bank declared the Kingdom’s health situation to be “one of the worst in the developing world” in 1995, when healthcare workers were paid around $10 to $20 per month.

Pay for public healthcare workers has doubled from 2004 to 2014 in accordance with government policies. But raising wages for the public sector requires increasing pay for other civil service employees in tandem.

When people are paying out of pocket anyway, they want to get good care, get to the top of the list

Cambodia’s healthcare system has come under more direct government control in the last decade. In 1996, the Kingdom relied on contracted NGOs to provide healthcare services. The system transitioned to “special operating agencies” in 2009, through which hospitals and health centres were given greater autonomy and funding incentives for fulfilling certain healthcare objectives.

For example, midwives receive between $10 to $15 for every birth. Even with incentives, 60% of the cost is covered directly by patients, the WHO reported. As a result, informal payments to healthcare providers by patients remain common. Midwives are also the most likely to receive side payments, Transparency International found.

“It’s inevitable there are going to be informal payments,” Annear said. “Because when people are paying out of pocket anyway, they want to get good care, get to the top of the list and not wait until everyone else has been dealt with.”

Regardless of the potential higher income at private clinics, recent UHS graduate Yanuth said she plans to start in the public sector, which offers job security and exposure to more patients.

She remains hopeful employment at a public facility will boost her credibility early in her career, perhaps leading to a private practice bearing her name.

“Here usually you have to get a name [for yourself] at a public hospital first,” Yanuth said. “Then you could get famous and open your own clinic.”

This article is a part of an ongoing partnership with Transparency International Cambodia meant to accentuate issues along with practical solutions concerning good governance and anti-corruption in Cambodia. Learn more about the partnership here.