Phnom Kulen, Cambodia – “From here, you would have been able to see the entire city,” Dr Jean-Baptiste Chevance says, gesturing to the obscuring green wash of trees, vines, shrubs and creepers crowding the five-tiered sandstone and laterite pyramid we stand atop of. “All of this forest would have been cleared. You would have seen highways and roads leading to the pyramid, a sprawling wooden royal palace to the north, brick temples standing in perfect alignment, huge reservoirs and a complex network of canals and dykes.”

The French archaeologist points out postholes that once supported galleries of ceramic tiles. Next to us stands a sandstone pedestal where a lost lingam – a phallic representation of Shiva, the Hindu god of creation and destruction – would have been ritually bathed. Until they were rooted out of the area in 1996, a Khmer Rouge radio antennae stood at the exact same spot: the highest point for miles.

“This temple,” 39-year-old Chevance says, “was once the centre of the Khmer universe.”

Forty kilometres northeast of Angkor Wat, the limestone cliffs of Phnom Kulen tower above the region’s rice-growing plains. To many Cambodians, the forested plateau is one of the most sacred sites in the country.

According to an inscription found in Thailand’s Sa Kaeo province, in 802CE it was at Phnom Kulen that King Jayavarman II declared independence from Java and himself the devaraja (the universal monarch) of a fractured country he managed to unify through conquests and alliances, thus birthing the Khmer Empire – an empire that would go on to dominate the region for the next six centuries.

Inscriptions from the 10th and 11th centuries also described a city called Mahendraparvata, or ‘Mountain of the Great Indra’, as being one of Jayavarman II’s capitals. Beginning in the 1880s, successive teams of French researchers sought to find traces of this abandoned city atop Phnom Kulen. These scholars documented crumbling 9th-Century temples such as the aforementioned Prasat Rong Chen pyramid and the brick tower of Prasat Damrei Krap, but found no conclusive evidence of settlement.

“The 30-or-so temples they found were just dots on a map to us,” says Chevance, who fronts the Archaeology and Development Foundation (ADF), Phnom Kulen’s leading research outfit. “Lidar connected the dots and gave us a completely new view of the city.”

Lidar, an acronym for ‘Light Detection and Ranging’, is a remote sensing tool traditionally used in areas such as mining and coastal management. Operating similarly to radar, it is able to calculate subtle differences in surface elevations by emitting hundreds of thousands of laser pulses per second, then measuring the time it takes them to return to their source. When mounted to an aircraft and combined with GPS technology, Lidar systems can create highly detailed topographical maps, even of areas that are densely forested.

For one day in April of last year, a helicopter outfitted with a million-dollar Lidar system scanned a 37-square-kilometre swathe of Phnom Kulen as part of a 370-square-kilometre survey of several Angkorian sites. The entire operation was coordinated by University of Sydney archaeologist Dr Damian Evans and carried out at cost by the Indonesian branch of McElhanney, a 103-year-old Canadian surveying, mapping and engineering firm. While Lidar had previously been used to map jungle-shrouded ruins in Mesoamerica, this $250,000 project was the first of its kind in Asia and the largest archaeological Lidar survey ever conducted. The survey provided researchers with a better understanding of Angkorian settlement patterns, but perhaps it most exciting revelation was the 1,200-year-old city of Mahendraparvata.

“When I first began analysing the Lidar data, I was shocked,” Stéphane De Greef, ADF’s volunteer cartographer says.

“I couldn’t believe it – I couldn’t sleep at night. Slowly, as I worked through the data, a complex and well-planned urban network was revealed. The city had highways as wide as 80 metres and eight kilometres long, and the roads aligned on a grid. It also sported an intricate hydrological system, and we were able to see plots and mounds denoting habitations and previously undocumented temples. All of this was focused around Prasat Rong Chen, and most of it had been hidden from us by the forest. This city, which had to have been planned in advance, predates Angkor and was bigger than Phnom Penh.”

Chevance, nonetheless, emphatically states that Mahendraparvata was never a “lost” city.

“The media have been sensationalising the story of our discovery since it first broke in June,” he says, referring to how news stories frequently make it seem as though Mahendraparvata materialised from the ether. “The ‘lost city’ term reporters have been using is a misnomer, as Mahendraparvata’s existence was known for decades. We didn’t choose an area to survey at random, but chose one based on years of research.”

There have been other issues with how this story has been reported. Because the findings were first revealed by Australia’s Fairfax Media, the University of Sydney is often credited with the discovery, though their essential efforts (which consisted of coordinating and overseeing the entire Lidar mission) did not include ground verifications at Phnom Kulen. On the flipside, despite his crucial involvement and thousands of hours of work, De Greef is seldom mentioned. Only four reporters, moreover, have actually made the trip to the plateau, yet many of the stories written about the ancient city (which are often accompanied by misleading photographs from the Angkor Archaeological Park) are peppered with grandiose descriptions of forgotten ruins. These reporters would be disappointed to learn that the reality is a bit more banal.

All of the newly discovered temples are little more than piles of crumbling brick; and, outside of the few previously documented temples, archaeologically speaking, there really isn’t that much to see atop Phnom Kulen.

“The real discovery is not the existence of the city,” Chevance clarifies, “but its scope and complexity: the nearly invisible features revealed by Lidar.”

The ADF team races on dirt bikes along narrow mud paths, splashing through creeks and passing hamlets, woodland, minefields and bedraggled plantations, startling cattle and children and getting clipped by low-hanging trees. “This is my dream job,” Sakada Sakhoeun, ADF’s young Cambodian archaeologist, shouts back at me. “I love being able to do something that betters my country.”

Ahead, De Greef stops at an undulating field covered in stunted vegetation. He dismounts from his bike and eyes his handheld GPS.

“Right now, we’re standing inside this,” De Greef says, pointing to a 300-by-500-metre rectangle highlighted on the GPS screen. Within it, a series of parallel ridges are spaced exactly ten metres apart. “I have no idea what it is.”

With his motorcycle, GPS and machete, De Greef has been exploring Phnom Kulen for nearly a year, inspecting every line, bump and depression revealed by the Lidar data – data that he has been meticulously analysing since July last year.

“We have to confirm everything on the ground,” De Greef says. “Sometimes, what we think are towering temples are dense clusters of trees or termite hills. And sometimes what is clearly an archaeological feature on the map – like a road or an enclosure – can’t be seen, even if we’re right on top of it.”

De Greef leads the way through a shallow gully, pushing aside branches and vines until we reach a vertical wall of living rock. The Belgian points out tool marks etched into the sandstone.

De Greef, Chevance and Sakhoeun discuss what the rectangle on the GPS screen could have been: A quarry? An unfinished reservoir? The opposite end of the structure backs onto a perfectly straight tree-shaded channel of clear water. De Greef, an amateur entomologist, points out a massive twisting Arhynchobdellida leech that I had mistaken for a small snake.

“Do you see the light coming through here?” De Greef says, his auburn hair illuminated in the dappled sunlight filtering through the trees. “If light can reach the ground, Lidar can let us see surface impressions of buried archaeological features.”

We work back through the brush, eventually emerging on a rolling moonscape of blackened tree stumps, tangled weeds and a jumbled mix of rice shoots, pineapples, young watermelons and cornstalks: a new slash-and-burn farm.

“Phnom Kulen is supposed to be a protected national park, but its people are destroying it,” Chevance says. To preserve Phnom Kulen, ADF promotes alternative sources of income generation for the plateau’s 4,000 inhabitants, such as fish and mushroom farming. It also hires locals to work on archaeological projects.

A middle-aged woman in sandals and threadbare floral pyjamas tends to the field. Smiling shyly, she offers us an unripe watermelon. Sakhoeun explains that she has been hired to work on digs in the past.

“Does she have any idea about what lies under her feet?” I ask Sakhoeun.

The two speak.

“She knows that Phnom Kulen is important,” Sakhoeun says. “But like most people, she had no idea that this was a city.”

The full scale of Mahendraparvata is still unknown. Ground verifications are ongoing and excavations have only just begun.

Moreover, with ancient roads leading to the very edges of the 37-square-kilometre Lidar map, Chevance is trying to raise funds for a second Lidar campaign next year.

“I’d like to survey five times the area we’ve already covered,” he says. “Our work here has only just begun.”

Going underground

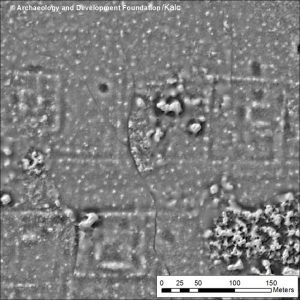

This image displays surface impressions of buried archaeological features such as one of Mahendraparvata’s main east-west roads, square housing plots, ponds and mounds where habitations made of perishable materials once stood (lighter colours signify raised features, darker ones signify depressions).

This article was edited by Southeast Asia Globe staff on 14 November 2013