Siek Ork had been living with his partner for four years when one day, in late 2021, everything changed. He started feeling sick with a fever and joint pain. It wasn’t Covid.

His partner suggested he get checked for HIV. Ork was surprised and dismayed at the request, but took the advice and went to Phnom Penh to run the test. He was positive.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the results.” Siek Ork said. “I had never been with any other man. How could this happen?”

Siek Ork found out that his partner had been cheating on him for almost two years, and, although he refused to be tested for HIV, his boyfriend admitted there was a high chance that he had been positive for a while.

The couple broke up and Siek Ork moved to Phnom Penh from his home province to start a new life. He hoped to find more support and understanding from the community in the capital.

“If I stayed there, I knew people would judge me a lot. In remote areas, the community does not yet understand HIV yet,” Siek Ork said. “I already had problems with my family when they found out I was gay. They couldn’t take this.”

He’s now one of approximately 74,000 people living with HIV in Cambodia – a number now growing at a quickening rate, alarming public health officials. The official yearly count of newly found infections doubled between 2018 and 2021, according to the National AIDS Authority (NAA), rising from about 500 to more than 1,100.

The recent spike in recorded infections has confounded more than a decade of successes in curbing the spread of HIV in the kingdom. But leaders of the NAA say lingering complications from the Covid-19 pandemic, plus a top-down approach to health governance and systemic failures to include input from those most at-risk are undermining their efforts to control the virus.

NAA vice-chairman Dr Tia Phalla said men who have sex with men, transgender people, and sex workers and their partners are rarely invited to participate in policy-making directly impacting their own lives in Cambodia.

“Their participation in drafting effective mechanisms is essential,” said Phalla.

Need for inclusive participation

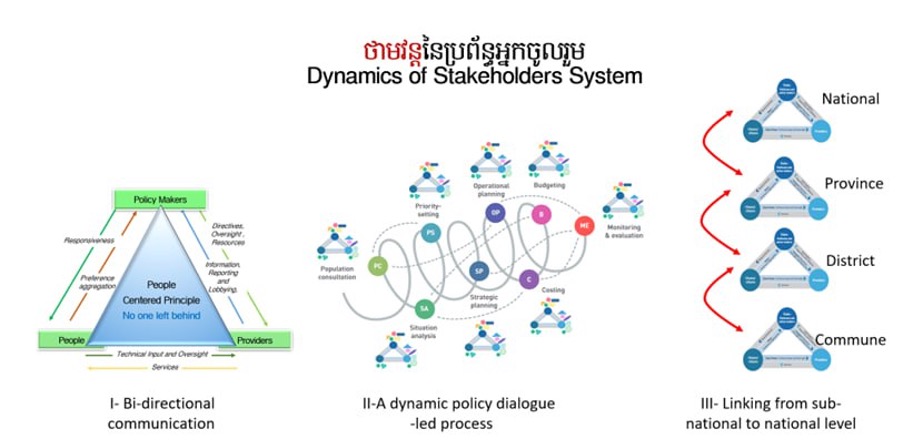

In 2016, the Ministry of Health – which oversees the NAA – announced a new programme with support from United Nations programme UNAIDS to encourage collaborative policy-making between the government, service providers and at-risk groups.

But Phalla said these efforts, known as the Dynamic of Stakeholders System, have shown no visible progress due to the lack of inclusion of key populations.

“If we don’t change our mindset and start valuing the participation of HIV patients in the policy-making procedure, nothing will ever change. Infections will just keep increasing instead,” he said.

In Cambodia, the absence of affected groups stems from a broader, top-down approach to governance in which high-ranking entities make decisions for others in society, Phalla explained. His 30 years of experience taught him that target individuals are often uncomfortable sharing their needs before government authorities or health system representatives because of the power imbalance between them.

“A body cannot stand with just one leg,” Phalla said. “Both are equally important and necessary for the balance of a person. And so is the government and affected population.”

Even the NAA is subject to this top-down hierarchy. Phalla said the authority is often left out of decision-making about HIV, and is left to observe the Health Ministry and service providers mostly act on their own.

Cambodia is aiming to reach zero new HIV infections by 2025 while trying to become fully independent from external financial sources or foreign non-governmental organisations such as USAID. International funds allocated to HIV prevention in Cambodia have been steadily decreasing according to Dr Tep Navuth, the NAA director of planning, monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

“We have very little funding for HIV prevention programs right now,” Navuth said. “With little international support and limited domestic financial availability, it is not a surprise that more than a thousand people still get infected every year.”

Recent data collected by UNAIDS in cooperation with the NAA shows a great disparity between infection rates and the national allocation of funding to HIV prevention and response.

Statistics collected by the authority revealed that 15% of the national HIV-related budget is allocated to HIV prevention. But with 72% of new yearly infections found among at-risk groups, only 7% of that total HIV budget is used for treatment and prevention among these groups.

Boosting that last number is one of NAA’s top priorities, according to Navuth.

Not enough

According to a historical study published in 2006, only three of 12,414 people living with HIV across the country in 1999 were receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART).

In 2003 the Global Fund started funding the inclusion of ART in the national healthcare system, enhancing the government’s HIV response.

Today, according to some of the most recent data collected by UNAIDS, of the estimated 84% of people living with HIV in Cambodia who know their status, 99% are on treatment and 97% are considered virally suppressed. That means the amount of viral particles in their blood has become undetectable.

Despite that progress, UNAIDS country director Patricia Ongpin warns that challenges still remain, and feelings of shame and fear often prevent those with HIV from receiving proper treatment.

“People might have not heard about [the spread of HIV], but that doesn’t mean that we should stop paying attention to it,” said Ongpin, who also oversees the agency’s work in Laos and Malaysia.

Ongpin lauded Cambodia’s successes in controlling HIV as “a great achievement” that was made possible through a highly targeted response. But at the same time, she said generalised information is not easily accessible to the public, meaning that especially the youngest generations lack basic knowledge on disease prevention.

More than a thousand children under the age of 15 in Cambodia are living with HIV, according to Ongpin, and of these only a slim majority are currently receiving treatment.

“If people start getting to know better how and where to get HIV testing, as well as how to prevent and respond to HIV, Cambodia will be on a good way towards ending AIDS,” Ongpin said.

Cambodian youths lack awareness

But the recent increase in infections is not entirely to blame on high-ranking institutions or policymakers, said Phalla. A multitude of other social factors had a crucial impact on this issue, including the Covid pandemic, new cultural norms for the youths, increased intravenous drug use, and less awareness.

Covid has contributed to increasing poverty levels across the country, which hit almost 18% of the population, according to national statistics shared by the NAA. The economic challenges forced the HIV-vulnerable community to avoid the costs of STD/HIV tests or treatment as well as causing an alarming decrease in the use of condoms.

“Those kinds of protections seemed to have become an unaffordable luxury for many,” Phalla said.

As Covid restrictions urged limited social interaction, people had to stay home with their partners or families and avoid clinics or hospitals. Outreach programs were also interrupted during the pandemic, moving most of awareness-building activities online – causing a further decline in access to information for the general public.

The NAA employs people from at-risk groups to work as professional community outreach organisers, paying $250 monthly to educate their peers about HIV on a full-time basis. But Phalla says the NAA is looking to restructure this program to attract more participants, as the money isn’t enough to interest those with better-paid jobs.

Phalla said men who have sex with men are generally more reluctant to be involved in any HIV-related programs because of the stigma attached to the virus and discrimination against them, which is still strong in Cambodia. Families or employers often reject them, especially in remote areas and if the individual lives with HIV.

“If you pull one leaf out from a plant, it would dry up quickly,” said Phalla of the vulnerability of men who have sex with men or those living with HIV who are shunned by their families.

“While the plant (family) remains green and healthy, the separated leaf dries up. Which one of them would you use to set a fire? The dry leaf of course.”

Siek Ork is a living example of the hardships such people face when they lack family support.

“I couldn’t stay there one more day,” he said. “It was unbearable seeing my family’s suffering, knowing about my condition.”

Because of a lack of family acceptance of their sexuality, Phalla said, men such as Siek Ork may feel forced to avoid seeking external support or information.

“The more we listen, the more we have people involved. That way awareness increases, and stigma decreases, thus we will have fewer infections,” he said.