Some of the most successful companies on the planet have proved that they don’t always know best

Doing a Ratner

Famous for uttering one of the most notorious gaffes in corporate history, retail tycoon Gerald Ratner effectively killed his company and reputation on April 23, 1991. At an Institute of Directors dinner, the owner of Ratners, a hugely successful UK high-street jewellery chain, joked that one of his firm’s products was “total crap” and boasted that some of its earrings were “cheaper than a Marks & Spencer prawn sandwich but probably wouldn’t last as long”. The speech cost him a £650,000 salary, wiped £500m from the value of Ratners, slashed a billion-pound turnover almost over night and coined the ultimate business gaffe phrase ‘doing a Ratner’.

Feeling blue

Not one to let convention inhibit creativity, Manchester-based Factory Records gave their musicians free reign to indulge their originality with outstanding results. This freedom was also extended to Peter Saville, who was tasked with designing the sleeve for New Order’s 1983 single “Blue Monday”. Having seen a floppy disc for the first time, Saville conceived the sleeve of the single as a replica. It was bold, it was original and it was expensive. The sleeve’s high-production costs meant that Factory lost money with every single sold; which only became a major problem when “Blue Monday” went on to become the biggest selling 12”single of all time.

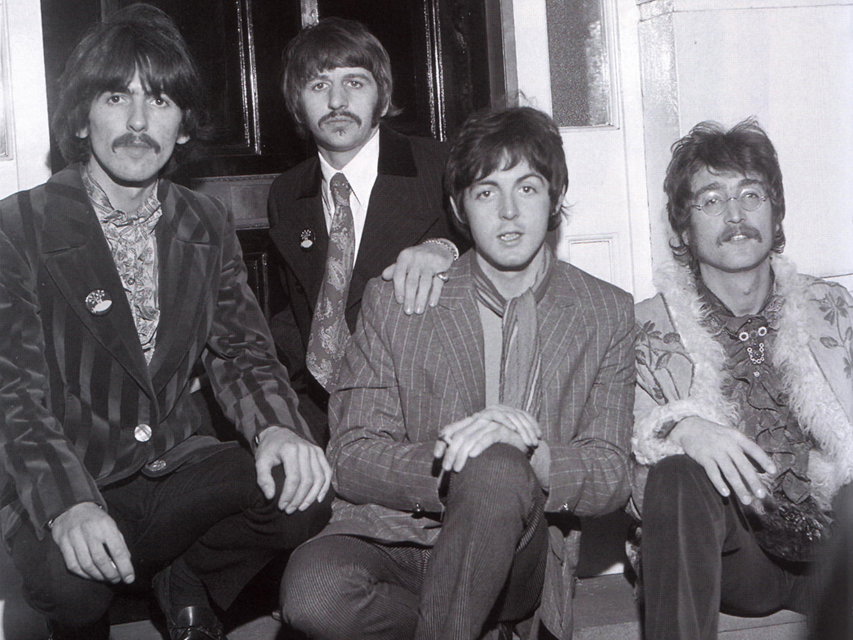

Beatles bummed

In 1962, Decca Records dashed the hopes of four young British musicians when it refused to sign them, claiming that “they had no future in showbusiness” because guitar groups were on their way out. It was a decision that has since been branded one of the biggest mistakes in music history. The fab four from Liverpool realised their dreams when EMI signed them a few months later and they went on to rewrite the history of music and become one of the biggest bands the world has ever seen, shifting more than one billion units. Decca, you should have signed The Beatles.

A right coke up

Few corporate rivalries can match the intense battle between Pepsi and Coca-Cola in the mid-1980s, a tense time in ‘the Cola War’. It was a period that saw Pepsi steadily chip away at Coke’s domination and both companies’ advertising campaigns go into hyperdrive. Nervous at Pepsi’s increasing market share, Coca-Cola concocted what would become one of the company’s worst marketing disasters: New Coke. The new soft drink replaced the original formula with disastrous consequences and was resoundingly rebuffed by an outraged public. Sales plummeted and Coca-Cola quickly learned its lesson. It yanked New Coke from the shelves and restored calm by restocking what is now named Classic Coca-Cola.

Opening the flood gates

In 1980, IBM dominated the world’s computer industry and wanted to expand into the growing niche market of personal computers. Requiring an operating system, IBM licensed a young start-up company called Microsoft to write the operating software for their soon-to-be-released product, the IBM PC. Microsoft, headed by Bill Gates and Paul Allen, signed a no-royalties deal with a desperate IBM that allowed them to keep the right to licence the operating system to other PC makers. IBM’s miscalculation, described as the “single worst mistake in the history of enterprise on earth”, allowed Microsoft to clone the IBM PC and offer a similar, but far cheaper, product. The move broke IBM’s iron grip on the computer industry and brought Microsoft the riches it needed to finance its blast into the business stratosphere. By the early 1990s, Bill Gates was the richest man in the world.