Walking into a cavernous room lined with humming printers, the space doesn’t quite have the illicit ambience one might expect from a pirate’s den.

One can provide their flashdrive to a bored-looking employee and answer a few simple questions: Which file? A4 or B5? Plastic or soft cover? Two hours later, a freshly-printed book is ready for the low price of about $3. It’s hard to believe a process this simple is robbing Cambodian authors and publishers of hundreds of thousands of dollars in sales every year.

Maybe more difficult to believe is that in Cambodia, the blatant piracy that is now the bane of Cambodian publishers’ livelihoods was once the lifeboat of education in the aftermath of the violent anti-intelligentsia movement of the Khmer Rouge. Forty years ago, in the early 1980s, Hok Sothik was one of many students hand-copying from one shared, tatty textbook in his primary school classroom.

“The books were very, very rare,” said Sothik, now the director of SIPAR, a non-governmental organisation promoting literacy in Cambodia. “We can see [from] the colour of the book, a lot of [passing], a lot of time, a lot of people used the book before you.”

But it wasn’t just schoolbooks then that students diligently copied out by hand. Sothik, who is also the president of the Cambodian Library Association and vice president of the Cambodia Book Publishers Association, also remembers copying novels so he would have something to read besides textbooks. He’s not alone in that.

“People didn’t have the opportunity to read, because after the Khmer Rouge, most of the books were lost,” said Chhor Sivleng, head librarian at the Center for Khmer Studies. “Everything was lost.”

Today, as Cambodia attempts to build a modern literary culture, those in the publishing industry say progress is stifled when much of the population is still dependent on the low-cost copy culture that once kept education afloat. Though the heyday of mass photocopying is over, piracy prevails in translated works by established Cambodian publishing houses, which often have spotty records for recognising copyright laws. As a UN-designated “least-developed country”, Cambodia has for years been exempt from the core intellectual property rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Thanks in part to two prior extensions of the enforcement deadline for the Agreement of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), piracy of foreign artistic and literary content has long flourished in exempted countries such as Cambodia.

But that might not be the case for long, as the most recent deadline is finally coming due July 1 of this year. Unless enforcement is pushed back yet again, a possibility thanks to a proposal last year from the African nation of Chad, the last safe ports for the world’s remaining book pirates could soon face a reckoning.

While there’s little research done on the financial losses from book piracy in Cambodia, the 2019 Cambodian Annual Book Fair, attended by over 180,000 people, had a turnover of some 1 million dollars over three days, with half the books sold translated from a foreign language.

As Sothik estimates about 70% of translated books sold in Cambodia are pirated, this could easily add up to more than hundreds of thousands of dollars in losses for authors and publishers every year.

Online piracy, making printing easier as it puts hundreds of thousands of books at peoples’ fingertips, is now also part of this changing conversation. Advocates of the practice argue piracy is necessary for accessibility, providing affordable foreign language books for students, but opponents like Phnom Penh-based publishing house Kampu-Mera insist that it is Cambodia’s literary scene that will pay the ultimate price.

“People believe in the culture of sharing,” So Phina, Kampu-Mera co-founder, told the Globe. “They share these [online books] in terms of good intentions – in fact, it harms the book industry.”

With the new hunger from a literature-starved population, consumer demand drove Cambodia’s book pirate economy in an urgent and necessary way in the post-Khmer Rouge era.

From the critical need of textbooks for students who were slowly trickling back to school after a four-year interruption, to the more sly romance novels rented by women from houses and cafes, the introduction of technology – from the hand crank Roneo copier in the 80s, to the photocopier of the 90s – only brought more counterfeits into the burgeoning market.

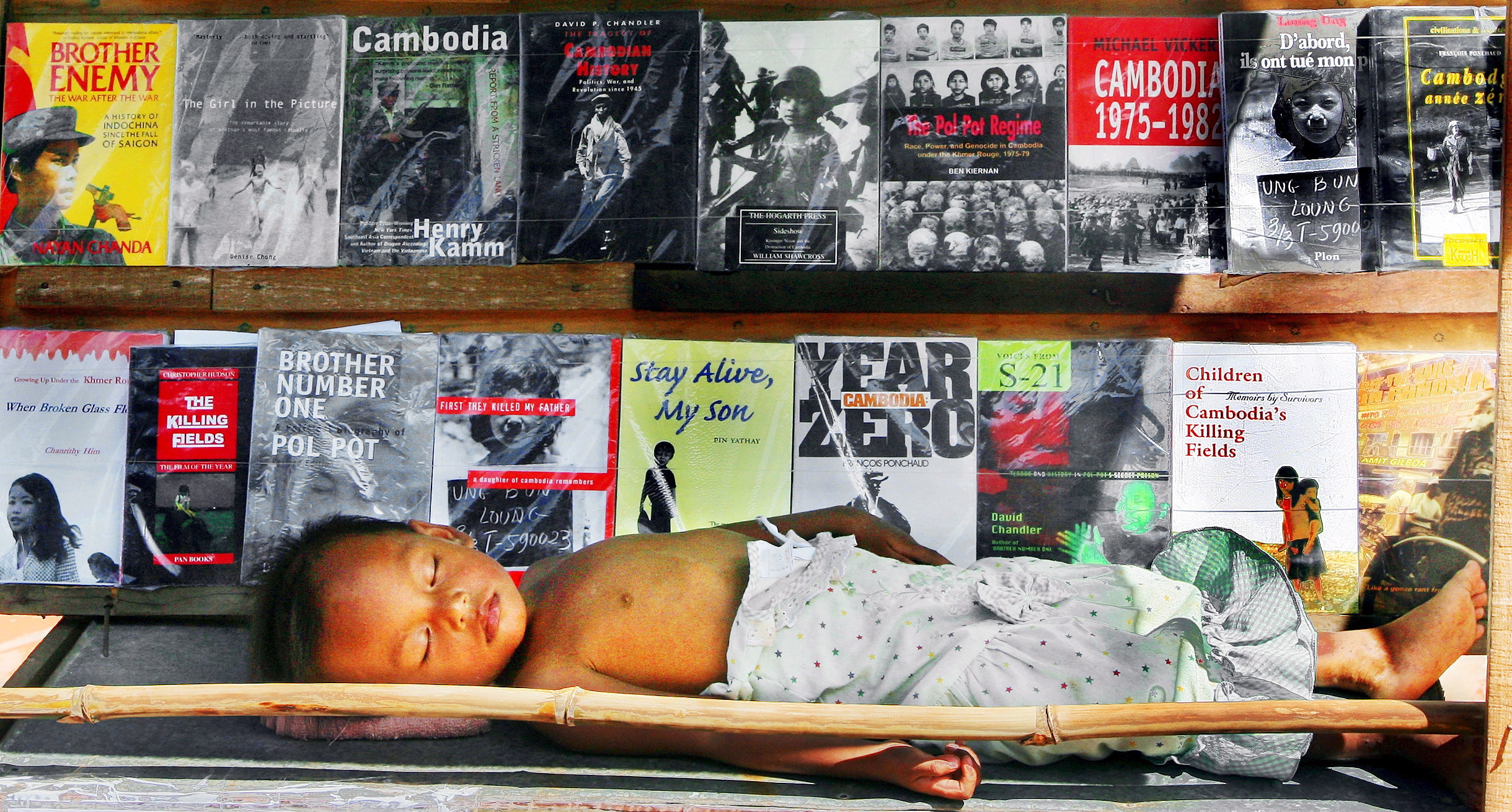

This era saw a proliferation of pirated books sold in the markets: Cambodian and Khmer Rouge history, French and English language books. There was little thought given to who owned the intellectual property.

“I don’t think people were concerned about copyright because they didn’t understand the role of copyrights. The people who survived the Khmer Rouge, I think that they forgot about copyright,” Sothik said.

Photocopying from existing books [to sell] in the markets and kiosks at a cheap price, this practice was seen from the 80s until nearly 2010

Remnants of this frenzied period of piracy remain evident in many places books are sold today, taking the form of askew pages and awkward formatting. They remained a fixed part of Cambodia’s literary history until relatively recently.

“Photocopying from existing books [to sell] in the markets and kiosks at a cheap price, this practice was seen from the 80s until nearly 2010,” said Huot Socheata, another Kampu-Mera co-founder. “The bootleggers were mostly bookshops themselves. All kinds of books were copied: Graphic novels, novels, educational books, Dhama books.”

But today, the industry has evolved, with most in agreement that piracy isn’t what it used to be in Cambodia. Sivleng says the library at the Center for Khmer Studies allows students, who photocopy mostly for their studies, to duplicate only up to one third of a book to protect the author’s rights, making exceptions for research that is otherwise difficult to obtain.

“Sometimes they like the book very much, but they cannot get them at the market or at the bookstore, so they ask for photocopies,” Sivleng said. “Sometimes, it’s because of the price too.”

Sivleng says foreign language books are the most frequently copied in her library as their prices on the legitimate market are considerably higher than Khmer books, which can be bought for a few dollars. Kampu-Mera’s Phina says another reason for the popularity of foreign language books in print shops is that publishers in the US and Europe are less likely to take issue than Cambodian publishing houses.

Socheata believes piracy often becomes an issue of short-term vision and money, with many Cambodian counterfeiters and readers often not aware of the team of writers, illustrators, editors, proofreaders, and printers who make up the process and need to be paid for their work.

Socheata says there is still the perception of books as luxury items among Cambodians, referencing common rhetoric used attempting to justify piracy in the Kingdom.

“One may say: ‘We are from a poor country where there are no writers and other resources due to the Khmer Rouge regime. On one hand, we can do nothing, and on the other hand, we can copy something – what would be a better choice?’”

The need for books was certainly dire after 1979, with Sothik saying it’s unlikely many books survived the first year under the Khmer Rouge occupation. While Pol Pot’s regime promoted an agrarian society through mass killings and forced population movement, the most literate and educated Cambodians were specially targeted by the cadres. Books taken to villages and hidden in houses were quickly lost due to frequent shuffling of multiple families and unrelenting surveillance of soldiers.

Chhor Sivleng remembers her university days spent copying books by hand for extra cash in the post-Khmer Rouge era of the 1980s. Novels that were provided to test readers, like friends or publishers, occasionally ended up on students’ tables. After making ten or twenty copies collectively, the students provided their savvy employer with copies for them to rent out of their homes for a fee to eager readers.

“We get two benefits from them. First, we can earn money. Second, it’s like reading without paying,” Sivleng said.

But what was once an essential practice to preserve any type of book is now curbing an industry eager to improve upon itself. A historic reliance on piracy fuels a lack of creativity when new authors can’t make money in the trade and publishers lose out on a market brimming illegitimate copies.

This small-press form of piracy isn’t the biggest culprit of authors and publishers losing ground on the legitimate market these days, though. Today, more established publishing houses are somewhat common in Cambodia – but just because these presses are operating on a larger scale, that doesn’t mean they’re any more legal than those of the hand-copying age.

Phina says this larger scale piracy is one of the most common methods today in the Kingdom.

“There’s not many real publishers in Cambodia, people are just printers,” Phina said. “There’s no word in Khmer to call a publisher, so we use the same word.”

Today, the conversation is shifting to one about intellectual property, focusing on the need for publishing houses to attain the rights before translating works into Khmer from foreign languages.

“From my understanding, Cambodia has never been a signatory member of Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works until very recently,” Socheata said, referencing an international agreement that came before TRIPS and formed the basis for the more easily enforced WTO rules.

Socheata referenced books previously translated into Khmer and published without attaining the rights, even before the Khmer Rouge, such as George Orwell’s Animal Farm and Jean-Paul Sartre’s The Wall. Kampu-Mera is one of the few publishing houses in Cambodia today that adheres to intellectual property laws, having recently produced official Khmer translations of classic literature like Albert Camus’ The Outsider.

We have to work together, not only for the publisher or the reader or the government, we have to work together to change this mentality, this culture

Sothik says despite the Law on Copyrights and Related Rights of 2003, which protects authors’ rights and an affordable process with which authors can establish rights to their creative works in Cambodia under the Ministry of Culture, copyright fees for translating international titles can range anywhere from $500 to $1000 for one American title. For less-than-legal publishing houses without that kind of cash, it’s not difficult to see why they opt to forgo the negotiating process.

Phina says there are multiple trainings each year by the Ministry of Culture to help publishers and writers better understand copyright law, but believes there should be more. But without a government crackdown on illegal publishing and printing, the problem persists.

“There’s no law enforcement properly in this country, so they just take advantage,” Phina said. “The Ministry of Culture are quite aware of this [counterfeiting], they know. But I used to hear one of the officers say that ‘We have to open one eye and close one eye.’”

Sothik believes it’s the government’s role to enforce copyright and intellectual property laws such as the Berne Convention, and that a year or two of education for illegitimate publishing houses could help improve Cambodia’s standing in the literary scene.

“We have to start by educating the people,” Sothik said. “We have to work together, not only for the publisher or the reader or the government, we have to work together to change this mentality, this culture.”