Maman or Mother? When it comes to the correct translation of Albert Camus’ 1942 novel L’Étranger, the devil is in the details.

The debate surrounding semantics begins with the book’s very first line. “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte” reads the famously emotionless opening declaration by Meursault, the book’s French-Algerian protagonist.

Attempting to smooth its transition, the first translators of the English-language version of the book (which would be known as The Stranger or The Outsider) interpreted the line as – “Mother died today”.

But to Christophe Macquet, those four (or three) words are deserving of more consideration. A co-translator on the first Khmer-language translation of L’Étranger for almost five decades, he explained how crucial this first line is for how the reader perceives Meursault and the subsequent story,

“The first line is very important,” Macquet told the Globe. “In French, the word maman is informal, similar to the English saying of mum. It’s strange, because the stranger is a guy who is detached – he looks at the world from behind a window – but he says maman, which is a soft and gentle word to call your mother.”

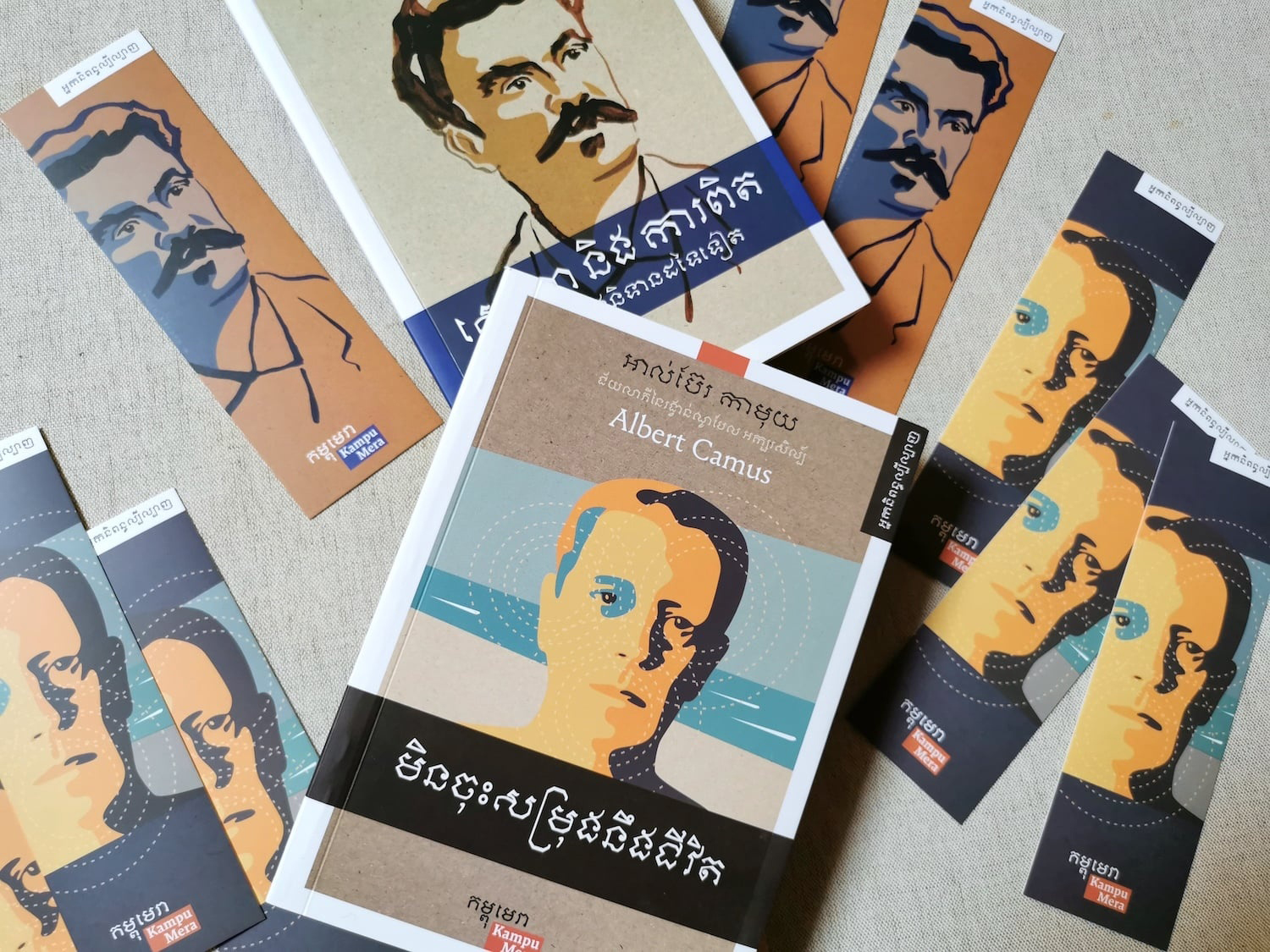

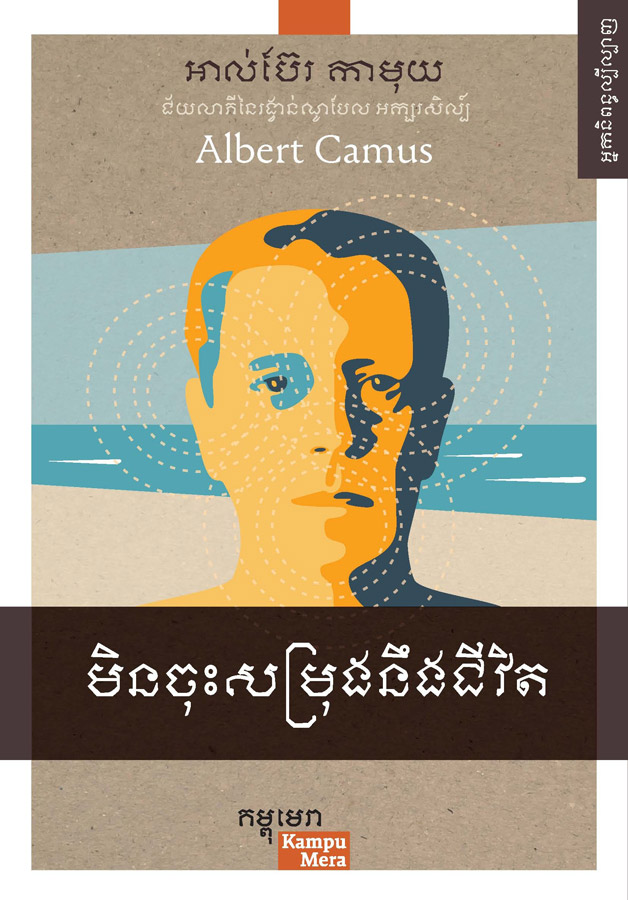

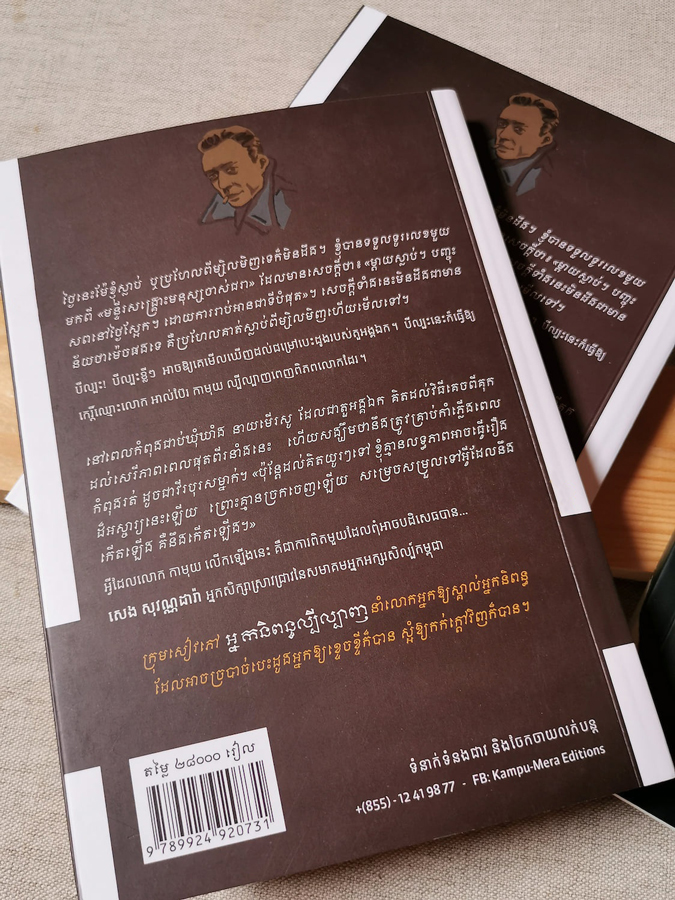

Macquet is part of an effort with Cambodian publishing house Kampu-Mera to bring new voices and old classics to Khmer paperbacks. Established in 2015 by Socheata Huot, alongside friend and fellow author So Phina, the small publishing house located in Phnom Penh is looking to produce high-quality literature in a market where there has long been a shortage of it.

“There was demand and a gap for different sorts of literature, a need to bring something else to the audience,” said Socheata. “That’s why we wanted to create something new, that’s how we came up with Kampu-Mera.”

We’ve put together a good mix – some fresh new writers from Cambodia, but also some classics as well

Released on July 25 of this year, the Khmer translation of The Outsider became Kampu-Mera’s sixth book and second translated from French – the first being a collection of short stories by writer Guy de Maupassant.

“We’ve put together a good mix – some fresh new writers from Cambodia, but also some classics as well,” said Socheata.

With Camus’ The Plague finding an audience as customers looked for reason during the height of the pandemic, there was arguably no better time to publish a Khmer translation of The Outsider – Camus’ absurdist, existentialist novel following the life and execution of Meursault. In the book, Meursault is ostracised for his apparent lack of emotion for his mother’s passing.

“It’s a literary masterpiece,” said Socheata. “We wanted to publish it again for a new audience.”

Two translators – Macquet and Khmer counterpart Be Puch – were tasked with bringing the 1942 novel to life in Khmer, while five Khmer writers sub-edited the translation. A special Khmer font – Chrieng Classic – was redesigned to make the text as easy as possible to read for the new edition, while the translation was supported by a UNESCO programme looking to publish classic world literature into Khmer.

“For me, this publication was a real collective piece of work,” said Macquet.

This most recent publication of The Outsider marks a further encouraging step to bringing literary classics to Cambodia, in Khmer, for a new generation of readers.

“It’s worth it because the selection of classic literature available in Khmer is very low,” said Frenchman Macquet, who first arrived to teach at the Royal University of Phnom Penh in 1994 on its French Literature programme. At RUPP, he would teach now-colleagues Socheata and Be Puch. “It’s very important to be able to read pieces of work from all over because it will help open peoples’ minds to ideas.”

Literature flourished in post-independence Cambodia, with a vibrant community of writers and intellectuals fluent in both Khmer and French. But by the 1970s, war was spilling over from neighbouring Vietnam and upheaval en-route. In 1975, the Khmer Rouge came to power.

Emblematic of the Maoist regime’s persecution of anything intellectual was the state of the National Library in Phnom Penh. Used as a stable and piggery providing pork for Khmer Rouge soldiers posted in the capital, books were reported to have been scattered, dumped or used as firewood.

Indeed, while Kampu-Mera have reintroduced this piece of classic literature back to a Cambodian audience, their edition is not the first publication of The Outsider in Khmer, with an earlier version lost to those years of upheaval.

Some translations are so bad, it’s easier to start it again from the beginning – but this one was good enough to work off

First translated in 1973 by Yi Chheang Eng, a professor of philosophy in the capital, the copy was published without the rights from the Camus estate and never since reprinted. Published a little over a year before the Fall of Phnom Penh in April 1975, copies of the book were lost and the whereabouts of Chheang Eng too.

“I read, sadly, that he disappeared during this period and it’s not possible to find any members of his family,” said Macquet. Copies of the 1973 edition, while incredibly difficult to find, still exist – Macquet himself stumbled upon one in the late 1990s at a stall on the side of the road in Phnom Penh, proving an invaluable slice of luck for his own translation. “It’s very, very hard to find the book,” he emphasised.

Macquet explained that while the 1973 translation does include mistakes and strays often from Camus’ original work, it’s well written and good enough to use as a building block. “Because some translations are so bad, it’s easier to start it again from the beginning – but this one was good enough to work off,” he said. “The imagery in the writing is very vivid.”

Macquet and co-translator Be Puch would go insofar as to give credit to Chheang Eng as one of the original translators in their version of the book. But for everyone involved with this latest translation project, it was imperative to not only get the rights from the Camus estate – which they did – but to make the Khmer translation as faithful to the author’s original work as possible.

“I think we have to respect the original French text – that’s really important,” said Macquet. “The family of Camus were very happy to know that we wanted to respect the original text and be as close to it as possible.”

Translating the work into Khmer took close to two years, trying to both ensure faithful interpretation of the original, transcending into Khmer and retaining what Macquet said was the beauty of the text. “It had to be beautiful – if it’s not beautiful like it is in French, you won’t want to read it,” he said.

Macquet said the Khmer language lends itself well to translation, thanks to its depth and richness. He added that he has a harder time translating back into French, such is the broad reservoir of vocabulary in Khmer.

“You have a lot of words in the Khmer vocabulary so you can translate almost everything,” he said. “People mistakenly think it is a ‘lesser’ language or harder to translate into, but this isn’t the case at all.”

How then, with such an armoury of Khmer vocabulary, did Macquet and Be Puch start the famous first line in their edition? With the Khmer equivalent of “maman” – while retaining the word order as used in Camus’ original.

Slowly, surely, the selection of world literature in Khmer is increasing and Kampu-Mera wants to continue adding to its collection, to help bring new and revised works to the country. So Phina is currently translating into Khmer a collection of Indian novelist Balai Chand Mukhopadhyay’s short stories, bringing the poet’s work into Khmer for the first time.

“A lot of people have not had a chance to read books such as these – missing out on the sheer pleasure of them,” said Socheata. “By bringing these works into Khmer we hope to share this joy with multiple generations of Cambodians.”