Macy-Châu Diễm Trần is a Vietnamese-American activist, artist, and educator who currently lives in Chiang Mai, Thailand, where she works at EarthRights International as a facilitator/trainer for community leaders and activists across the Mekong region.

As my alarm harassed me to wake up for work late last month, I rolled over to check my phone to see if there were any messages from my friends and family in the US. This is a common routine, as during my sleeping hours in Thailand, my US community is awake.

Instead of seeing the usual few messages, there are 20 notifications from WhatsApp. From the other side of the world, I entered a surreal, dream-like state of scrolling through local journalists’ Twitter feeds as the rage, hurt, and grief of George Floyd’s murder shook my home city and lit it ablaze.

With every live update from my friends came another dose of anxiety and fear. Fires had broken out in places I knew and loved. The Asian supermarket where my family bought groceries, the Chinese restaurant where we celebrated countless graduations, weddings, and celebrations, and the gas station next to my grandma’s house – all burned down.

All the while, as Black activists demanded their right to live, there have been provocateurs, among them far-right armed groups, instigating violence and chaos. As activists carried the memory of George Floyd as they chanted his name, police tear gassed and arrested protesters, and US President Donald Trump threatened the use of the military and provoked people to shoot protestors. My heart ached for all of the hurt and loss, but also revelled in the people power radiating from the streets.

I was born and raised in Minnesota, US, though my lineage spans across the sea to my family’s ancestral lands of Viet Nam. With injustice against Black people coming to light globally, I longed to be home, supporting in whatever way I can, connected to the city and the people there that raised me as they braced and prepared for what feels like a revolutionary upheaval of violent police systems.

Instead, I found myself on the other side of the world, working in solidarity with Mekong communities, which felt like it had nothing to do with anti-Black racism.

Rather than compartmentalising these global struggles, this moment provides Southeast Asian activists an opportunity to intentionally expand the impact and understanding of their local work to connect to the global challenges of militarism and racism.

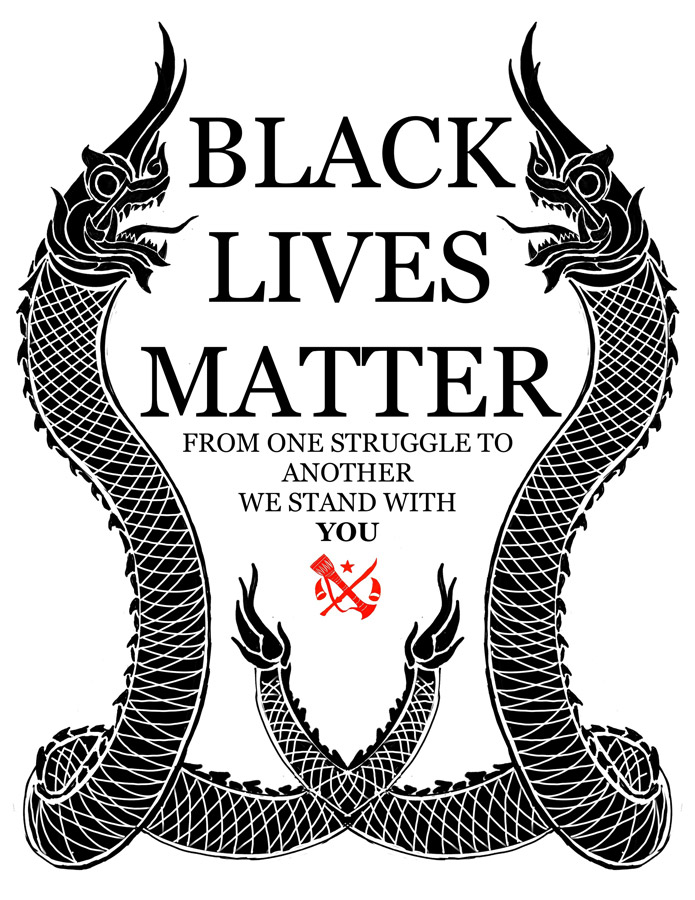

To bridge these coexisting struggles for justice is to understand the vital importance of the Black Lives Matter movement in the US to inspire conversations, strategies, and energy into local movements in Southeast Asia in which we similarly see a vision for our communities to be safe and secure from the oppression of state-sanctioned violence and destruction of land and people.

As a Vietnamese-American activist in the US, I came to Southeast Asia three years ago to deepen my relationship with my Vietnamese roots and its relationship to activism, courage, and liberation. In this time, I have been blessed to bear witness to the immense power of Southeast Asian struggle and resilience.

All across the Mekong region, I heard stories of ethnic and indigenous villages being blazed by state militaries, stories of natural water sources no longer drinkable due to industrial pollution, stories of unjust detainment, discrimination, and torture. At the same time, I learned from community elders in Thailand who successfully campaigned against a mega-dam in their community for 30 years, learned about the power of boundary breaking music when my indigenous and ethnic friends from Myanmar use hip hop and rap in their native languages as a tool to share their experience with oppression and call for hope. I also learned from the limitless faith and perseverance of religious minorities in Vietnam whose places of worship were burned down but who still continue to practice their religion underground.

Meanwhile, in the US, month after month, year after year, Black folks still mourn the loss of their loved ones at the hands of police brutality and racist health and education systems. With Black Americans dying from Covid-19 at triple the rate of white Americans, coinciding with the recent murders of Breonna Taylor, a 26 year old Black woman who was shot by police in her own apartment, George Floyd, a Black man murdered by a white police officer who kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes, and Ahmaud Arbery, a young Black man who was jogging when he was shot by two white men, we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg of anti-Black racism in the US. These are not new issues; rather, an American norm born from a legacy of enslaving Black people.

Because the US has a global media presence, the protests in the States began coming up in conversation here in Southeast Asia. When I discussed with my colleagues and friends around the Mekong about what’s happening – the police tactics, the suppression of protesters, the militarisation – I was met with unsurprised nods. They drew parallels to their own experiences and communities that are discriminated against, displaced, abducted, and killed off by the government and the military.

We had conversations about media censorship that manipulated public narratives, and the police state that suppressed freedom of assembly and speech. Through these conversations, my friends and I began bridging the liberatory struggles of this region to those in the US, as we discussed the global extent of racism and militarism, and its ongoing presence in many of my friends’ lives here.

It is well-known that the Black race is the most oppressed and the most exploited of the human family

Ho Chi Minh

Over the weeks the protests took the nation and the world by storm, I listened to the ways in which Black Lives Matter inspired Southeast Asians to discuss the oppressive politics happening in their own backyard. Although Southeast Asians’ experiences with state sanctioned oppression cannot be equated to the specific struggles of Black Americans, a learning opportunity emerges from the cross-sections of colonisation, capitalism, and militarism.

From ethnic youth groups in Myanmar sharing their solidarity with Black Americans, to indigenous Papuans in Indonesia speaking out about their experiences with state-sanctioned persecution with their own Papuan Lives Matter movement, the peoples of this region began harnessing the momentum of the Black justice movement in the US to express their own grief and people power.

From this, a broader public representation of Black Southeast Asians has also emerged, such as Thai-Mali vlogger Natthawadee “Suzie” Waikalo, who has spoken openly about facing discrimination as a Black-Thai woman in Thailand. Additionally, all across the region, Southeast Asian locals and Black expats/foreigners have joined forces to hold space to process, educate, and show solidarity for the US Black Lives Matter protests such as a Black Lives Matter vigil organised by my own community in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and a community fair and panel in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

The connections between human rights issues in Southeast Asia and Black America is not a new phenomena. In his speech Beyond Vietnam, Black Civil Rights leader and preacher Martin Luther King Jr. expressed:

“The war in Vietnam is but a symptom of a far deeper malady within the American spirit, and if we ignore this sobering reality, we will find ourselves organizing ‘clergy and laymen concerned’ committees for the next generation. They will be concerned about Guatemala and Peru. They will be concerned about Thailand and Cambodia. They will be concerned about Mozambique and South Africa. We will be marching for these and a dozen other names and attending rallies without end unless there is a significant and profound change in American life and policy.“

A year later after giving this speech opposing the extreme violence of the Vietnam-American war, Dr. King was assassinated. Black folks shaking up and uprooting the foundations of racism in the US reverberates globally. It is through their protests that they challenge the capitalist and militarised systems in the US that still hold influence in Southeast Asia through neocolonial models of harmful development, education, and media. Simultaneously, the long history and ongoing endeavours of Southeast Asian communities to build campaigns and movements opposing oppression in their everyday lives similarly calls to what Dr. King described as a “radical revolution of values” shifting “from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society”.

Ho Chi Minh, the North Vietnamese communist leader and politician, also wrote on the persecution of Black Americans. In his 1924 piece, On Lynching and the Ku Klux Klan, he writes:

“It is well-known that the Black race is the most oppressed and the most exploited of the human family. It is well-known that the spread of capitalism and the discovery of the New World had as an immediate result the rebirth of slavery, which was for centuries a scourge for the Negroes and a bitter disgrace for mankind. What everyone does not perhaps know is that after sixty-five years of so-called emancipation, American Negroes still endure atrocious moral and material sufferings, of which the most cruel and horrible is the custom of lynching.“

Almost a century later, the Black American protest for freedom rages on. Recently, on 10 June, Robert Fuller, a 24 year-old Black man, was found hung from a tree in California. While police initially ruled it a suicide, family members and community activists have demanded an investigation into whether he was lynched.

We, the peoples of Southeast Asia, have many parallels to draw in our own fight for the human rights of refugees, the poor, political dissidents, and indigenous, ethnic minority peoples, and Black Southeast Asians who similarly face violence and discrimination at the hands of oppressive state systems and militaries. Despite both Martin Luther King Jr. and Ho Chi Minh speaking from a historical instance, the contemporary echoes and reproductions of oppression are still relevant today, as both Black Americans and marginalised Southeast Asians still demand that their basic human rights must be heard, respected, and felt at a personal, systemic, and global level.

Local resilience and perseverance must always premise a global narrative for justice, and vice versa. As the Black Lives Matter movement in the US is given an international spotlight, I sometimes hear a sentiment in which Southeast Asians feel that our historical and on-going struggles and oppression here have never been heard at the same scale, resulting in a sense of tension over attention and resources.

However, it is important now, more than ever, to connect international solidarities and learn about each others’ social movements as our oppressors (and the systems they propagate) continue to grow and maintain their power, networks, and money in increasingly globalised ways.

With our combined knowledge, skills, and strategies, it is particularly striking to me how powerful we (local and global activists) actually are, as this movement presents us with an opportunity to listen to each other’s interrelated trauma, movement building, and hopes and dreams to build a liberated future for our communities, together.

For in-language (Thai, Khmer, Burmese,Vietnamese, Chinese, Lao) resources about the Black Lives Matter movement, please click here. The reflections in this article are only as a result of the meaningful conversations I had between me, my local Southeast Asian, Asian American, and Black American friends and comrades who have helped me organise and write my thoughts in an intentional and considerate way that honours everyone’s global and local struggles for justice.

This story is part of our ongoing The View From Southeast Asia series, tackling issues of identity, ethnicity, rights, discrimination and culture across Southeast Asia. If you have your own reflections to share, you can contact the Globe at a.mccready@globemediaasia.com.