Following a positive test on his flight, Globe reporter Alexi Demetriadi is currently being held in quarantine at a Phnom Penh hotel. He will be writing about his experiences in a series of blog posts over the next two weeks. He is also posting on a daily basis on his Twitter account.

Sydney’s Kingsford Smith airport was eerily silent.

It’s already not a major transit hub due to its geographical location and, with the Australian government banning citizens from leaving and foreigners from entering, the airport was one of the quietest I’ve seen. Travelling in a time of Covid-19 is cautious and socially distanced.

The departure hall, littered with high-end designer outlets and duty-free shopping, was boarded up. Chairs at the Heineken bar were overturned, shops were locked behind gates and even the once-glowing golden arches of McDonalds were dark and unplugged.

A pharmacy and a family run-Turkish café were the only outlets operating – the gozleme from the café was a particular highlight and was most passenger’s pre-flight meal of choice.

I was going to Cambodia, traveling to begin work at the Globe. Just a week earlier, my colleague, Andrew, had done the same, flying from Chicago’s O’Hare airport and transiting through New York City via John F. Kennedy airport.

We were traveling during one of the sharpest-ever downturns in global air traffic. According to 15 June statistics from the International Civil Aviation Organization, estimates of international passenger traffic for 2020 suggest an overall reduction of as many as 67% of seats offered by airlines. Thanks to ongoing pandemic conditions, that could amount to an overall decrease for the year of roughly 1.45 billion passengers flying around the world.

If even just one person on a flight tests positive, all fellow passengers must remain in a two-week hotel quarantine, after which they will test again to see if they’re clear to leave

Both of us were flying on Asiana Airlines, a South Korean carrier, and transiting through Seoul Incheon airport, one of the few major hubs in Asia currently allowing transit.

International borders have tightened or shut entirely to non-citizens as a public health measure during the pandemic. In Cambodia, tourist visas and visa-on-arrival schemes have both been suspended. For foreigners who can get a different kind of visa, the process of actually getting to the Phnom Penh airport, much less leaving it, has gotten harder over the past two weeks as the Cambodian government bulks up entry requirements to prevent the arrival of Covid-19 from abroad. So far, Cambodia has officially confirmed 130 cases of Covid-19 infection, eight of which have come in the past month or so from repatriated nationals.

These new measures require non-citizens to provide a “Covid certificate”, or negative Covid-19 test taken no more than 72 hours before arrival, and proof of health insurance covering no less than $50,000. Cambodian authorities are also testing all new arrivals for Covid-19 almost immediately after landing. After going through an enhanced customs and immigration check, passengers are shuttled to a testing station in a lobby area and then for a minimum one-night stay in a quarantine hotel while awaiting test results.

If even just one person on a flight tests positive, all fellow passengers must remain in a two-week hotel quarantine, after which they will test again to see if they’re clear to leave. Passengers on flights where all travelers test negative are allowed to return to their homes of long-term lodging, where they are asked to self-quarantine for two weeks before reporting for a second test.

To ensure newcomers have the means to pay, authorities have recently put in place a deposit scheme that requires all foreign arrivals to make a payment of $3,000 up-front upon arrival to cover any costs of potential quarantine or treatment. Authorities told me whatever costs are incurred will be subtracted from the deposit before its return.

My flight to Cambodia, Asiana Airlines flight OZ602, was a repatriation flight for the large Korean community living in Sydney and across Australia. As such, it was full, so even while we kept our distance in the airport, social distancing went out the window once boarding had finished. Asiana’s A350 was bursting at the seams with those returning to South Korea and a small minority, like myself, using Incheon as a stop-off point.

In Sydney, a socially distanced check-in for the flight spanned two zones and took over an hour and a half, a far cry from the new, automated, speedy check-in procedures now favoured by a number of airlines.

On the other side of the world, leaving the US took almost no time at all.

As in Kingford Smith, the terminals of JFK were completely devoid of people. For the first time, Andrew was aware of the cavernous spaces carved into the modern airport. Asiana Airline representatives at the New York hub read over his documentation when he presented himself for check-in and dropped off his bag; one of the agents told him they needed be extra careful now when dealing with passengers to Cambodia, as they’d just had one traveler rejected from entry to the Kingdom due to a visa issue.

“Cambodia is very strict now,” she said, nodding.

Andrew’s documents passed muster and the agent awarded him with a boarding pass. Feeling as if he’d passed the first real challenge of a long journey, he later boarded a flight to Seoul that was nearly empty.

Face masks were mandatory attire on both of our flights except for when we were eating the provided meals.

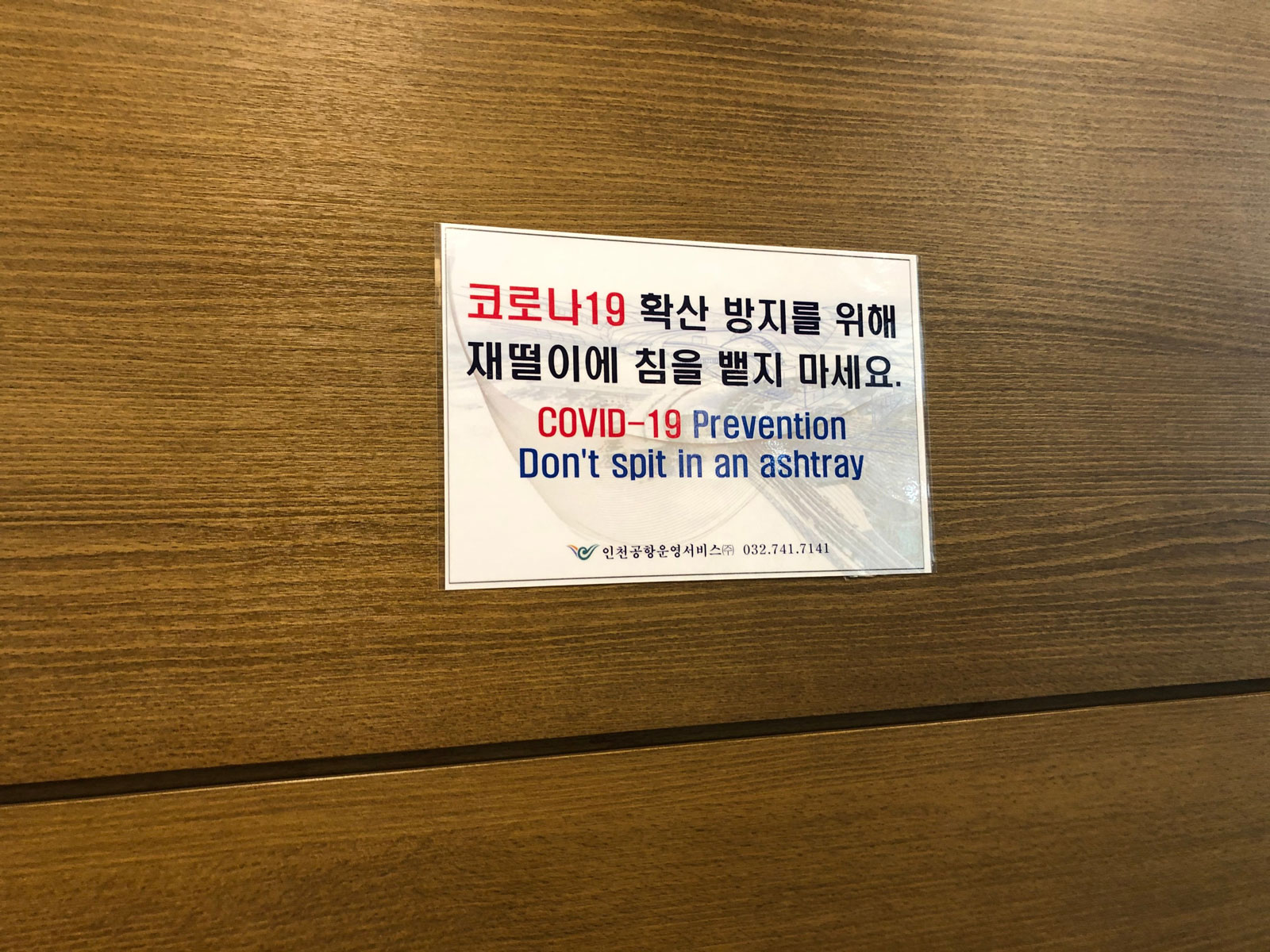

Coming from Australia, I touched down in the early hours of the morning at Seoul Incheon. Andrew landed in mid-afternoon, but both of us noted the mega-airport was quiet, with only one side of the usually full departure board listing departing flights.

A lonely whale of an A380 plane, a mammoth craft already hit badly by changing consumer attitudes in the aviation market even before the pandemic, sat dormant in the middle of the apron, its engine switched off. The terminal areas were nearly empty save for flight attendants, airport staff and a friendly robot humming along the floor, telling anyone in earshot to approach it for selfies and airport information while reminding us to be vigilant of Covid-19.

Flight OZ739, one of two departing Seoul for Phnom Penh, was made up of mostly Cambodians returning home and a few odd passengers entering the country for work. The young man sitting ahead of me had just graduated from a college in California and was returning home, while the young woman next to me was studying in Darwin, Australia. Both had chosen to travel home thanks to the shutdown caused by the pandemic.

When we got off the plane, we filed into two separate lines, one each for Cambodian and foreign passport holders. Agents checked our documents and collected our passports, promising to return them when we left quarantine. They occasionally picked at items lost in translation, questioning insurance policies with “unlimited” coverage — as they had no clearly visible dollar amount, some reviewers needed convincing these policies met the $50,000 requirement — and Covid-19 tests without an official-looking stamp or physician’s mark.

Andrew was fortunate with his arrival date and just barely missed having to pay the $3,000 deposit, as the requirement was not yet in practice. I was not so lucky and found myself swiping my credit card. The woman who collected my payment gave me a receipt slip with an individual ID number and a phone number to call to refund my deposit in two weeks when, theoretically, my cohort would be done quarantining if anyone on the plane tested positive.

Next came the dreaded Covid-19 swab test.

Arrivals from my flight snaked through the makeshift testing station, where passengers were briefly questioned and swabbed between wood partitions by medical officials shielded in gauzy head-to-toe personal protective equipment.

During the testing, one woman cried, someone else swore and even I screamed and tried to yank the hand of the doctor away from my face – all to no avail

I’ll say now that the Covid-19 tests I had in Australia were horrible, but this one made those look like nothing.

During the testing, one woman cried, someone else swore and even I screamed and tried to yank the hand of the doctor away from my face – all to no avail. The people behind me who heard my wailing must have been afraid of what awaited them in the testing station, the two young children behind me in the queue even more so.

Andrew was less traumatised by the swab but tells me he still found it “downright unpleasant”.

We were then bussed to a nearby hotel, the Tian Yi International, a little more than three kilometres from the airport to wait two nights for word on our test results. The price for a night here, which includes three meals during the day, is $87, though I’ve heard other travelers reporting different amounts. Andrew was placed in a double room with a roommate he met in the hotel lobby as the weary travelers took stock of their new surroundings. In a fun bit of traveler’s luck, the man was a friend-of-a-friend who happened to arrive at the Tian Yi in the same batch of newcomers. Ever the lucky one, all of Andrew’s fellow passengers tested negative and he was able to make his exit from quarantine in just a day-and-a-half.

You could say my own journey is still ongoing.

This morning, my would-be landlord for the month sent me a screenshot of a local news wire: ‘Passenger from Sunday’s Seoul flight tests positive for Covid-19.’

An anxious wait ensued. Was it our flight, or the earlier Korean Air flight?

A knock at the door followed by a temperature test and a translation from a fellow guest confirmed the bad news. The positive case was on our flight, meaning the remaining 111 of us were to be stuck in quarantine for a full two weeks.

If the test swab was the first jab, the update was a hard second.

Everyone so far has been professional and friendly and however much I will complain about that Covid-19 test, the measures are intended to keep people safe. Even in quarantine, the beer is cold, the balcony has a view and – most importantly – the plans in place to stop the spread of Covid-19 appear to be doing their job.

This story is part of the Globe’s Tales of the Pandemic series, a collection of personal essays from across Southeast Asia called covering different aspects of life during this unprecedented time in human history. If you’d like to contribute a personal essay of your own, please email your story of roughly 1,000 words to a.mccready@globemediaasia.com.