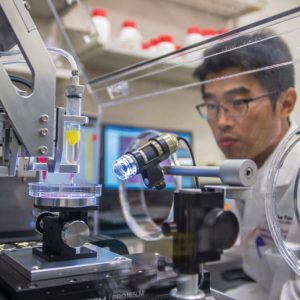

Fifteen years ago, the bioengineer Thomas Boland was sat in his lab at Clemson University, South Carolina, staring at an old Lexmark inkjet printer. He had a thought: the size of a typical human cell is roughly 25 micrometres – a micrometre is one thousandth of a millimetre – as is the size of a typical inkjet printer’s nozzle. Emptying the ink cartridge and filling it with collagen, he then glued black silicon onto a sheet of paper, typed his name into a Word document and hit ‘print’. A new technology was born: bioprinting.

Before the year was out, Boland and his team had printed E coli bacteria and larger animal cells. Three years later, he applied for the first patent on the technology to print living cells. The biological printouts, however, were only two-dimensional. At about the same time, other engineers began experimenting with 3D printers, which had been developed in the 1980s, to construct teeth, bones and prosthetic limbs. Boland altered his printers, and soon he was printing 3D cells layer upon layer. The rest, as they say, is history.

Today, bioprinting’s possibilities are becoming greater by the month. It is now possible to print blood vessels, lymph nodes, skin and hair. In the foreseeable future, it might be possible to print functioning organs for transplant into humans. Although the technology’s developments and breakthroughs have largely been made in Europe and the US, there is increasing confidence that Singapore can also stake a claim.

According to Mike Goh, senior assistant director at the Singapore Centre for 3D Printing (SC3DP), the development of bioprinting is intertwined with the growth of 3D printing, or additive manufacturing, as it is called by those in the industry. While traditional 3D printers construct objects made of plastics, metal and wax, modern bioprinters employ similar processes but instead use biological materials such as cells, bacteria and proteins.

“Singapore’s 3D-printing capabilities are comparable to the developed countries, as our government has been investing heavily in this area,” said Goh. “SC3DP has one of the best-equipped labs in the world [for 3D printing] and has been attracting leading researchers to the centre… We can make Singapore a leading centre for 3D printing in the world.”

Goh believes that these capabilities will equip Singapore’s researchers and engineers to cross over from traditional 3D printing to bioprinting.

In May 2013, Bio3D Technologies was formed, the first company to bring bioprinting technology to the city-state. Within two months, they had created Singapore’s first 3D bioprinter. After a series of patents and designs, in June they released the world’s first foldable 3D bioprinter, the Bio3D Explorer, for sale and lease.

Mingwei Fan is the director and a co-founder of Bio3D Technologies. “Many people think of bioprinting as ‘organ printing’. However, the possibility of using a bioprinted organ in a human is still quite distant,” he said. “I believe that bioprinting will instead benefit the research industry first.”

For example, researchers could experiment with how cells interact with bacteria and other biological materials in lab settings, or they could bioprint replica body parts to study the likelihood of complications during a surgery.

Another boon for researchers, and perhaps environmentalists, could arrive in the field of drug testing. Pharmaceutical companies will be able to test their drugs on living human tissues or cells, thereby ending the need for real-life ‘guinea pigs’. There have been suggestions that, within a couple of years, miniature human organs will be printed for this exact reason. In fact, in August, the US Food and Drug Administration approved the world’s first 3D-printed pill.

In another development for Singapore, Procter & Gamble, one of the world’s largest consumer goods companies, launched an initiative in the city-state in May. Candidates are able to submit research proposals for applications of bioprinting that would be relevant to the company in return for grants. This is part of a scheme initiated by the Singapore government’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research, which will see SGD60m ($43m) invested in bioprinting research over a five-year period.

“Bioprinting in Singapore and Southeast Asia is still lagging behind the West, especially the US,” Fan said. “Researchers and scientists in the US and Europe understand the technologies better and are more keen to explore bioprinting than their counterparts in Asia. In Singapore the challenge is increasing the awareness and understanding of 3D printing and bioprinting.”

However, Fan added that interest in bioprinting is picking up quickly in the city-state, as well as in South Korea and Japan. When asked if he believes that Singapore can establish itself as a significant global player in bioprinting, his reply was emphatic: “Definitely.”