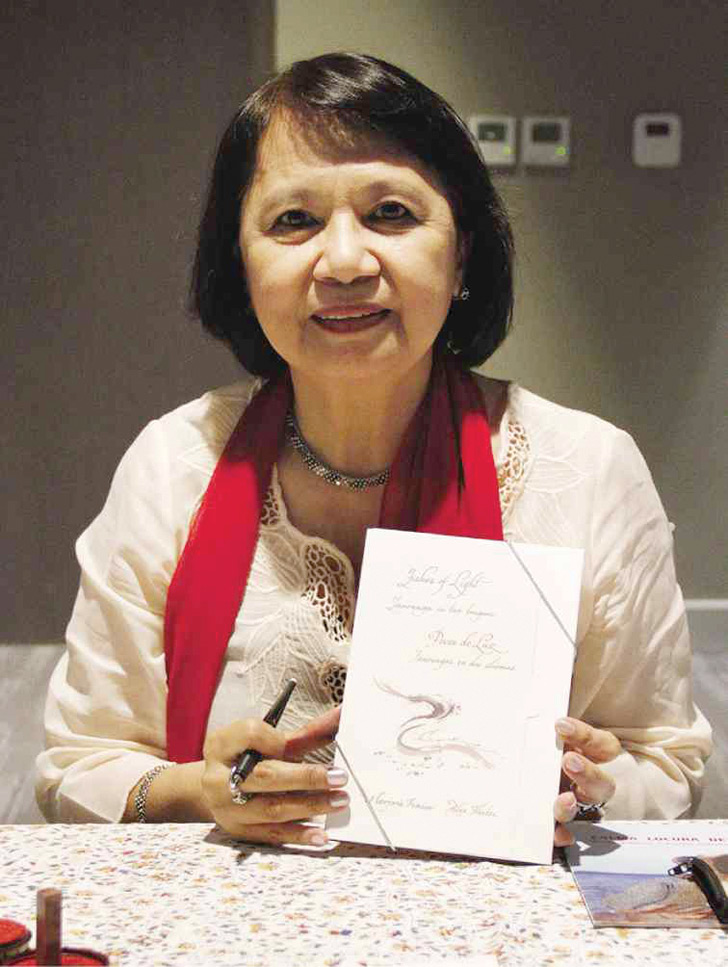

Marjorie Evasco

Born on the island of Bohol in the central Philippines, Marjorie Evasco’s first two collections of poetry each won the prestigious National Book Award for Poetry from the Manila Critics’ Circle. Writing in both English and her mother tongue of Cebuano, Evasco’s poetry infuses Western imagery with the wit and irony of her native literary tradition. In the Cordite Poetry Review, Evasco spoke of her work as a space to tease some kind of purpose from the urgent senselessness of day-to-day life: “A poem’s heart cares for and attends to its own mind and strives to sing the old stories in the face of pressures wrought in the world/s we live in, at this particular time, in this specific place.”

Zeyar Lynn

Widely regarded as the founder of the avant-garde ‘L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E’ poetry movement in Myanmar – a form emphasising the centrality of language in the creation of meaning that grew out of rising discontent with mainstream poetry in the late 1960s – Yangon-based poet, teacher and translator Zeyar Lynn has been a divisive figure in his home country. Initially damned for his translations of ‘decadent’ American literature, Lynn’s influence on a new generation of Myanmar poets cannot be overstated. In his poem “Chronicle of Kings”, Lynn paints the unsettling scene of a family awaiting the rebirth of the man whose abuses left his wife’s body “a refugee camp”: “All his children now have their own families/Whose child will be his incarnation?/We remain on the lookout for his shadow.”

Angkarn Chanthatip

“The Heart’s Fifth Chamber”, the title poem of Angkarn Chanthatip’s Southeast Asian Writers’ Prize-winning collection of the same name, is a dreamlike paean to the warmth and compassion that moves through the rest of the Thai poet’s work: “The heart dreams of peace/conquers misfortune, fans a fire that never goes out/stands firm and knows how to listen/Like rain, love and hope temper heat”. Growing up in Khon Kaen province in Thailand’s northeast, Chanthatip’s unsentimental portraits of those forced to the margins of Thai society emphasise the tension between the country’s agrarian roots and the rampant urbanisation of the present day.

Nguyen Do

Criticised by the oppressive literary establishment in Vietnam for the sombre undertones of his writing, poet and translator Nguyen Do divides his time between his home country and the less restrictive US. A committed translator of both Vietnamese and Western poetry, Do’s anthology Black Dog, Black Night: Contemporary Vietnamese Poetry was pivotal in bringing the full breadth of a new generation of Vietnamese voices to a wider audience. The last lines of his poem “Going to the North” expose the melancholy of a life lived between two worlds: “the radio doesn’t warn of the storm coming/but the stair steps have the feeling of fate’s vague prediction/u, u, u/our lives are smaller, smaller, as the train whistle sounds”.

Oka Rusmini

Raised in cosmopolitan Jakarta, award-winning poet and novelist Oka Rusmini’s move to rural Bali as a teenager brought the restrictive traditions of village life into sharp relief – particularly those surrounding the high-ranking Brahmana caste of her birth. Her controversial writing challenges the traditional taboos and prejudices against women that permeate conservative Balinese life. In her 1995 poem “Ceremony for Returning to the Land”, Rusmini mourns the increasing commodification of Balinese culture and the people’s bitter alienation from their own land: “and just to smell the land/the owners of the map, the/owners of the Badung river, the/owners of the sea/even the gods/have to pay for the scent of the/earth which is theirs”.