Positioning himself behind the lectern, Saifuddin began to read, point by point, Pakatan’s plans for reform, including asset declarations for politicians, term limits and the abolition of the unpopular Goods and Services Tax.

The audience, dressed in the colours of the coalition’s four parties, listened patiently as, in the same measured tone, he moved on to leadership issues – the subject of months of speculation in Malaysia’s largely government-controlled media.

In the front row of this banqueting hall atop a largely abandoned shopping mall in the city of Shah Alam was Mahathir Mohamad, the man who was the country’s prime minister for 22 years. He joined forces with the opposition last year. Mahathir and his wife sat alongside people who were once their political enemies, including Wan Azizah Wan Ismail, the current leader of the opposition and spouse of Anwar Ibrahim.

It was Mahathir who jailed Anwar, his former deputy, on charges of sodomy in the depths of the Asian Financial Crisis in 1998, unleashing a movement for reform with Anwar at the helm that has managed to whittle away at the support for the ruling alliance. Once again in jail on charges of sodomy – a crime in Malaysia, and in this case widely decried as politically motivated – Anwar is scheduled for release on June 8.

“Yang Amat Berbahagia Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad [is] candidate for prime minister,” said Saifuddin, showing his respect by using the full list of honorifics bestowed upon the 92-year-old. Like Mahathir, Saifuddin was once a member of the ruling United Malays National Organisation (UMNO).

The announcement prompted a chorus of cheers from the audience, as some of Mahathir’s most ardent supporters jumped to their feet, punching the air with delight.

Wan Azizah, the eye doctor who was thrust into politics upon her husband’s arrest and is now MP in Anwar’s old seat, was named Mahathir’s deputy should the coalition prevail. Sometimes dismissed as ‘soft’, Wan Azizah has proved a quietly determined presence over the past two decades of opposition politics. She said last year, during an interview with Al Jazeera, that she would give up her position for Anwar on his release.

“It wasn’t easy for Anwar Ibrahim to accept me,” Mahathir admitted in his first speech to the assembly – with what was, perhaps, more than a little understatement. As Wan Azizah had welcomed the veteran leader to the stage, her voice had cracked, tears welling in her eyes.

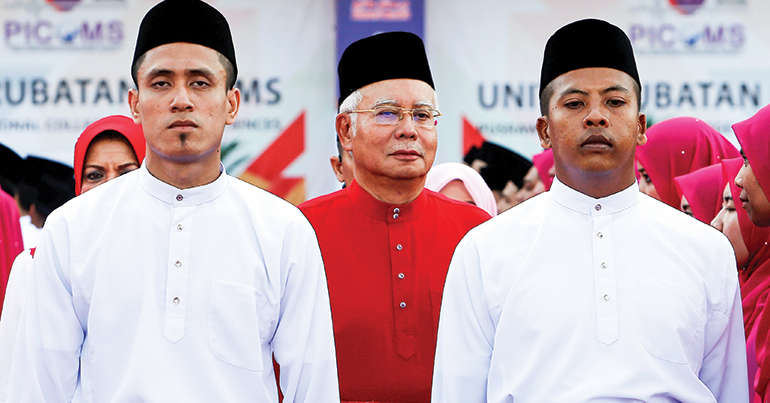

With a general election due by August, and Pakatan sensing its best chance yet to wrest power from the UMNO-dominated alliance that has run the country since independence 60 years ago, the decision may yet prove as groundbreaking to the country as Anwar’s sacking. The ruling coalition under Prime Minister Najib Razak is battling discontent over the cost of living and allegations of corruption that have triggered investigations and convictions across the world.

The prospect of Mahathir as prime minister – at least until Anwar is released and secures the pardon that will allow him to return to political life – should Pakatan win is a sign that the opposition wants to reach beyond its traditional middle-class, urban supporters to the rural Malays who have long helped sustain the UMNO’s power. But in doing so it must try to persuade people that a man who was often described as autocratic or even authoritarian while in power is now committed to reform.

Mahathir “is both a unifying and polarising figure”, observed Norshahril Saat, a fellow at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore, in a statement following the convention. “How [the opposition coalition] convinces the public about its move to embrace a figure it once scorned remains a challenge.”

Analysts say the opposition’s public disagreements over its leadership created an impression of disunity and provided grist to Najib and his backers’ claim that they couldn’t be trusted to run the country effectively. A December survey by polling company Merdeka Centre found support for Pakatan declining, with just 21% saying they were happy with the grouping – although few showed much appetite for the incumbent either.

Rafizi Ramli was one of the ten senior coalition members who helped broker the agreement on the group’s choices for prime minister and deputy, as well as each party’s allocation of seats.

Fuelled by chicken rice and Malaysia’s national dish of nasi lemak, the team spent three days holed up at the headquarters of Mahathir’s party, Parti Pribumi Bersatu, working the phones and thrashing out the details to secure a deal in time for the convention. After a “lot of give and take”, a “binding agreement” was finally signed at 8:49pm on the eve of the event, Rafizi said.

“We are ready to go back to our constituencies,” Rafizi told Southeast Asia Globe on the sidelines of the convention, acknowledging that the leadership debate might have weakened Pakatan while asserting that the agreement would ultimately strengthen the coalition. “It’s not about this person or that person. It’s about the overall strategy to resolve all the contentious issues. At every stage, we have the power structure in place, and that allows us to really focus on the battle against UMNO and whoever comes to their side.”

A potential spoiler is Pakatan’s former partner, Parti Islam SeMalaysia (PAS), which dropped out of the alliance in 2015. With Anwar in jail, policy differences exploded into the open as PAS stepped up its demands for the imposition of the Islamic penal code. The party insists it is independent, but it has moved closer to the UMNO since the split.

Mahathir’s elevation also risks making the election about competing visions of the past at a time when the middle-class, urban electorate – who make up much of Pakatan’s support base – want change. They acknowledge the veteran leader’s economic successes but question his political record, arguing that he helped contribute to the situation in which Malaysia now finds itself by undermining the country’s democratic institutions, including the judiciary and parliament.

“He does have a certain pull,” said Bridget Welsh, associate professor of political science at John Cabot University in Rome and an expert on Malaysian politics. “But it’s not consistent and it’s tied to a sense of nostalgia. It’s not reform-orientated, and it allows people to say: ‘What’s different?’”

There’s also Mahathir’s age, and that of the wider leadership. The average Pakatan leader is 64, compared with an average age of 30 for the country’s population. Wan Azizah is 65 and Anwar is 70.

“There’s a historical amnesia about Mahathir’s premiership,” said Netusha Naidu, a student at University of Nottingham Malaysia who questions whether a Pakatan under Mahathir can provide the reform she and other young voters wants to see. “People seem to forget that he was an authoritarian leader, [in power] at the same time as Suharto and Lee Kuan Yew; the time of ‘Asian values’. I don’t think he’s done enough to show that he’s changed as a person. It’s time for fresh, new faces – someone with no baggage.”

Sometimes when you vote, you don’t get the person you want. [But] being a strong voice for democracy is not just about voting every five years – it’s also what we’re prepared to do to ensure the institutional structures are strong

Young Malaysians are already among the most sceptical in the electorate. A survey commissioned last August by Watan, a non-profit set up to get more young people to vote, found that 40% of Malaysians aged 21 to 30 had not registered to vote. At the same time, at least 57% said they were dissatisfied with the way the country was headed.

Najib is seen as having an advantage despite the graft allegations and unhappiness over the cost of living. As the incumbent, he has greater financial resources, controls the mainstream media and has the benefit of constituencies that are heavily weighted towards his coalition’s traditional rural base – the UMNO did, after all, win more parliamentary seats and thus the last general election in 2013, despite the fact they lost the popular vote.

“The choices that are in front of us are not simple,” said Masjaliza Hamzah, Watan’s executive director. “Sometimes when you vote, you do not get the person you want. [But] being a strong voice for democracy is not just about voting every five years – it’s also about what we are prepared to do to ensure the institutional structures are strong. It’s not just one man, but a system.”

At the convention, successive Pakatan leaders were keen to stress their political successes and plans for reform. The coalition has been in charge of Selangor, Malaysia’s richest state, since 2008. A four-page glossy leaflet highlighted the electoral promises made, and kept, and the state government’s plans for 2018. Addressing the audience, its chief minister Azmin Ali vowed that the state would be a “model for a new [Pakatan-led] Malaysia”.

In the corridor outside the convention hall, members browsed books, posters and T-shirts emblazoned with the faces of the coalition’s leaders, including Mahathir. On a chalkboard set up for people to share their hopes for Malaysia, some had written their wish for “Tun”, as Mahathir is often known these days, to become premier again.

Throughout his political career, Mahathir has shown an uncanny ability to read Malaysia’s political winds. He might be in his 90s, but few would dare underestimate him in the battle to come. In waiting so long to call the election, Najib might also have thrown his opponents a lifeline: the time to reconcile their differences and a chance to focus their campaign on their vision for the country.

“It’s not that UMNO fears Mahathir most,” Rafizi said in between posing for selfies with party members. “It’s not that UMNO fears Anwar most. UMNO fears unity more than anything else, because a united opposition that has ironed out all its most contentious issues means a very focused and united force against them. We won’t take the bait to start shooting at each other, because all the guns are now outside.”