Winding through the narrow backstreets of Pecatu on Bali’s southern peninsula, the taxi flies through a roundabout, past a handful of foreign surfers presumably en route to Dreamland Beach, and plunges into lush, tropical vegetation.

We zip past posh vacation villas, ramshackle huts with thatched roofs and the odd spindly chicken. The jungle forest opens for a split second and the entrance to the home of Ashley Bickerton comes into view: A huge wooden gate flanked by a pair of stocky pillars, each of them topped with an acid-coloured, serpent-like head – a signature motif cast from the artist’s own dome and frequently used in his work since the mid-2000s.

One of Bickerton’s assistants opens the heavy gates, his greeting little more than a grunt, as a security camera peers down from above.

Up a steep, paved driveway and I’m greeted by Bickerton’s right-hand girl, Marcia, in the artist’s office-cum-studio. She says they’ve just wrapped up (quite literally) the work for “Ash’s” latest solo show, Junk Anthropologies, which will run at Singapore’s Gajah Gallery from April 26 until May 25. The show was born of Bickerton’s showing at this year’s Art Stage Singapore, where he exhibited a canvas that has informed these new works and where I met him for the first time.

Marcia gives a quick tour of the space, pointing out a work-in-progress that will be part of May’s Art Basel Hong Kong. The detail is exquisite and complex – a visual representation of what one imagines goes on inside the head of the American artist.

Having waited stage left for just the right amount of time to make a bit of an entrance, Bickerton appears at the top of a wooden staircase that leads to his cliff-top home. Wearing a t-shirt and baggy, knee-length shorts, exposing Polynesian tattoos that hark back to his years spent in Hawaii, he is feeling a bit dusty.

“I’ve been on an intense fast for the past four weeks. Last night I broke it quite gloriously,” he says, not quite regretting it. “I need a burger.”

Marcia is beckoned and sent on a run to pick up some grease and detox juices.

Bickerton, calm and welcoming with sun-bleached hair from days spent surfing, perches in front of his Mac and begins to chat about the show. Speaking with a British-softened American accent, he is prone to ranting at nobody in particular and to abrupt digressions – a conversation about an Indian art critic soon becomes a Bickerton-led discourse on Korean popular culture.

As we chat, a massive Labrador named Ruby bumbles in and begins licking me furiously. Bickerton says he had to build a $40,000 wall around his enormous property to keep Ruby and her pals from going on “murderous rampages” through his neighbours’ properties that sometimes claimed the lives of up to 13 innocent chickens. Ruby is followed into the office by an icy-eyed Husky named Haku, who Bickerton quickly shoos away.

“We’re not friends,” he states simply. “Is there some rule that you have to like all your dogs?” he adds, offering that the pooch’s life on his land, where it is fed every day, “sure beats ending up on a satay stick”.

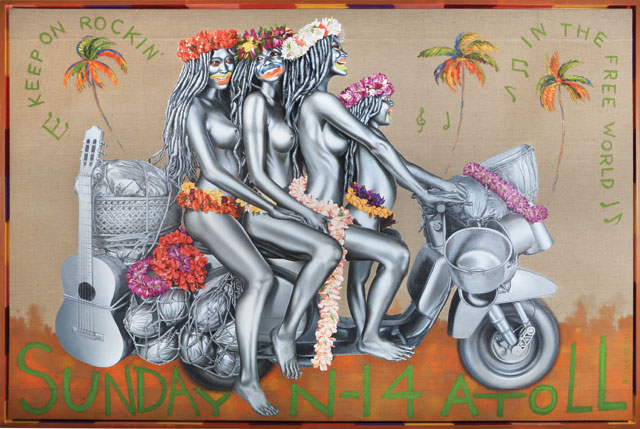

Bickerton’s work on Junk Anthropologies began shortly after our January meeting in Singapore, leaving him just three months to complete five of the six huge canvases that constitute the show.

“This time I’m playing with content and exoticism and history. That’s why it’s called Junk Anthropologies. You wanna talk about sexism and racism, yeah I’m fully aware. I’m almost scared…” he trails off. “Am I trying to just be provocative? Not really. Discursive? Certainly.”

Born in Barbados in 1959, Bickerton is a graduate of the California Institute of the Arts and was an important figure in New York’s art scene as part of the Neo-Geo movement of the 1980s. A 1986 group show that included Bickerton, Jeff Koons, Peter Halley and Meyer Vaisman, or the ‘Fab Four’, is the foundation upon which Bickerton’s identity still balances – despite him fleeing the East Village and relocating to Bali back in 1993.

The move to Indonesia’s most beloved tourist island represented a physical departure from a place Bickerton says “hurls people into the stratosphere to laud them and dollop them with sanguine praise. Then it’s a real sport to rip them out of the sky and stomp on them.” It also signalled a departure in his work, as he shifted from dealing with objects of desire to looking at the effects that desire has on its subject. At times it worked. At others it didn’t. But one thing was constant, he says.

“I actually refuse to fail. Failure is not an option. I’ve come close a couple of times though. I remember one time – I think it was ’96 in Bali – I thought it was over. It was almost time to pack up and go looking for a teaching job in Bumfuck, Texas.

“But I did these paintings. My gallery absolutely flipped out and didn’t know what to fucking do. They wanted to break them up into three – it’s one piece – which doesn’t make any fucking sense. That’s the whole point, it’s all me. It’s called ‘All That I Can Be’. If you took the seed that is Ashley Bickerton and put it in three different environments… you end up with three utterly different plants. And that’s what this is.”

The work featured three panels, each representing a different manifestation of Bickerton had he been the product of three alternative milieus: Bickski, an obese biker blotted with tattoos; A.B, a ’roid-munching Hollywood-type with blinding white teeth; and Ashleigh, a beanpole, bubble-breasted transsexual. The gallery had broken them up into three separate pieces when the Whitney Museum of American Art came along and bought them as a unit – a huge pay day for Bickerton. “Then all of a sudden,” he says, “Roberta Smith of The New York Times came along and called it one of the best comebacks in recent memory – and I was back.”

Since the comeback, his work has been described as “garish” by everyone from Ken Johnson of The New York Times to David Ebony in Art in America. He seems somewhat frightened of it being labelled kitsch, and is focused on anchoring it in parody, referencing the likes of Van Gogh and Gauguin.

“Some people refuse to acknowledge the new work and think: ‘Ashley’s lost his mind, with all this colour-soaked kitsch in the middle of some tropical island.’”

But, he says, he is simply giving the market – particularly Southeast Asian buyers and collectors who have been well known for their penchant for large-scale canvases – what it wants.

“If you fuckers don’t want digital, I’ll give you paintings, I’ll give you canvas. I’ll give you a canvas so canvas-y it’s burlap. I’ll give you stitching all over it so it looks like canvas and I’ll give you frames and I’ll sand the fuckers. So instead of using that machine there,” he says, pointing to a huge digital printer sitting next to his pair of Macs, “I use painters.”

This mode of operation – using a team of studio technicians to execute his work – planted its seed in Bickerton’s brain after he’d graduated from art school and attended a talk by Jack Goldstein, the photorealistic painter who committed suicide in 2003. Bickerton was his primary assistant for four years in the early 1980s.

“I’d developed all those [photorealistic painting] skills so I went straight up to him after the talk and said: ‘I’m moving to New York and I want to come work for you. I can do your paintings better than whoever is doing them now.’ And he just kind of laughed and said: ‘Yeah, sure.’ I didn’t think he’d remember me, but he did. And the rest is history, I guess.

“He was a bitter, crazy motherfucker. He was an incredibly difficult, complicated person. Basically, I wanted to kill him by the end of our relationship,” Bickerton says, somewhat nostalgically. “In the beginning it was great, because he treated me like an equal and brought me in and introduced me to a lot of people. I’m just out of art school and I had my hands all over the work and I’m actually contributing ideas, too. And in some cases they [the artworks] were going out to museums. He believed in me. But our relationship was flawed. By the end I would have been quite happy to drive a kitchen knife into his back – and I’m not violent.”

Nonetheless, the pair’s relationship has clearly had a lasting impact on Bickerton’s process. He currently works with a team of assistant painters, whose hands are all over his work, and he isn’t shy about saying so.

“Doing another artist’s work, there are certain rules. If it’s about the gesture, if there’s inflection or interpretation, only the artist can do it. If it’s merely rendering a photograph, that machine there can do it or any technician can do it. You’ll see that among all sorts of artists, from Rudy Stingle to Jeff Koons to Damien Hirst,” he explains. Hirst, the most famous of the Young British Artists and responsible for works such as “The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living” (or, that shark in a tank of formaldehyde), is in fact a good friend of Bickerton’s and an avid collector of his work.

At this point, Bickerton’s beautiful Balinese wife Cherry (who happens to be the model in many of his recent works) walks in and hands him a bracelet. He says his son found the wooden beads at a Xavier Rudd concert and his mother-in-law had restrung them for him. Marcia, all smiles, then returns with a chicken burger the size of Ruby’s slobbering head and a tray full of vibrantly coloured juices.

“Want a bite?” Ashley asks me, thrusting the gnawed snack toward my face, as the conversation turns back to those lofty New York days.

“I was hanging out with Basquiat just days before he died. He had a missing tooth. He kept drinking what I thought was iced tea but they were actually Long Island Iced Teas and he kept putting his whole mouth around the glass,” he says, as if shoving a tumbler down his throat with both hands, “turning them upside down. And he was walking around with his arm around me going: ‘I love your work. I love your work. I love those basketball tanks.’ I’m going: ‘That’s not me. That’s the other guy.’” Basquiat was referring to Jeff Koons’s “Three Ball Total Equilibrium Tank”.

Within a minute Bickerton’s burger is devoured. “I want another one,” he says. “It’s not that I drank that much last night, just that I haven’t drunk in a while.”

We talk a little about the shindig in question and I notice half a bottle of Absolut on the table behind him. He says that not a single photograph was taken among the artists and intellectuals in attendance. We share the opinion that living life (and interacting with art) through the lens of a camera or a smartphone is a crying shame.

Reluctantly throwing the soiled burger wrapper away after seeming to contemplate its crumpled emptiness for a few seconds, he brings up a live surf camera on the Mac to check the swell at his favourite beach. A wild storm is brewing overhead; leaves outside swirl and dip in the wind.

“I’m meant to be meeting Paul Theroux tomorrow,” he says of the legendary writer, author of The Great Railway Bazaar. “But it’s complicated. The surf is going to be huge.”