Suzann Victor speaks with a soft, almost childlike voice. A voice that makes it even more disconcerting when she discusses using human hair to spell out the word clitoris or reveals her fascination with the “creativity” employed when prisoners make deadly weapons from newspapers and other everyday objects.

“Sometimes we don’t know how to use freedom,” says the famed Singaporean artist. “I actually think that limitations sometimes force you to do absolutely the craziest thing, and that can be the most creative thing.”

It is a fascinating idea in a region with such an intractable history of colonialism, dictatorships and limited freedom of speech: Can oppression sometimes be – whisper it – a good thing for the artistic process?

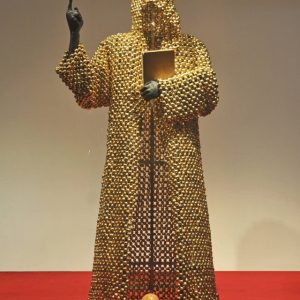

Here at Art Stage Singapore 2015, among the unsettling hyperrealist human sculpture of Sam Jinks, the prodigious toilet paper weaving of Wang Lei and the kaleidoscopic bigotry bashing of Gilbert & George, there are hundreds of artists, many of them Southeast Asian, most of whom have worked under duress of one kind or another.

“The way we, as humans, think has a lot to do with our history. In the end every artist is an individual, but they are also integrated somewhere in his or her own history and, without a doubt, that has a lot of influence in art,” says Lorenzo Rudolf, the straight-talking founder and director of Art Stage Singapore, the annual art fair that this year hosted more than 150 galleries from 27 countries. “What’s interesting is that it’s mainly emerging countries, such as those in Southeast Asia, where you have the most historical and political influence still today in art, especially when compared to the West. Of course, that means you need to know a bit about the region’s history in order to understand certain things.”

Colonisation saw the introduction of Western artistic techniques and ideas to Southeast Asia, from watercolour in Malaysia to neoclassicism in the Philippines. Questions of identity have pervaded regional art ever since, and works such as the “Spoliarium” by Filipino artist Juan Luna have gone down in history, hailed by locals as an example of their mastery of a medium learned under the colonisers’ tutelage.

According to Malaysian Shia Yih Yiing, 47, who often uses herself as the central figure in her paintings, for many artists there has always been a push and pull against colonisation. “The locals picked up these Western practices, so we were under a kind of art colonialism as well,” she says. “Ironically, I use Western techniques to show the problems brought here by the Western world, such as materialism and capitalism.”

For many Southeast Asian nations, however, the greatest oppression has come from within. Suharto, Marcos, Pol Pot, Than Shwe – the region’s recent history is littered with authoritarian leaders, and it could certainly be argued that repressive regimes of varying severity still run Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore and many other Asean nations.

Richard Streitmatter-Tran, 42, a Vietnamese-American sculptor based in Ho Chi Minh City, says that censorship is still an issue in his native country and even puts the current makeup of Ho Chi Minh City’s art scene – dominated, as it is, by small personable spaces – down to a “severe” government crackdown on an attempted biennale-style art event in 2006.

“We still have to apply for permits and other things, but artists get along in spite of that,” says Streitmatter-Tran. “[The situation] obviously results in self-censorship. Artists may make something for an exhibition in-country and make something different for shows outside.”

In Malaysia, Yiing has noticed increased censorship in recent years. She puts this down to the country becoming “more and more Islamist in its politics” and says that the result is many artists self-censoring due to their reliance on grants from various institutes, as well as a desire not to “cause problems” for event organisers. Artists, after all, don’t want art spaces to be closed down.

“One way we try to get around it is to put up notices so that, when people go in, it says they enter at their own risk. These are the types of preparations we have to make. You have to know how to protect yourself. I’ve had my warning already,” says Yiing, without elaborating.

Self-censorship in the arts, particularly when it becomes institutionalised, can certainly suppress creativity and ideas, and worries about public ‘outrage’ can cause cultural institutions to be overly cautious in their choice of work, according to a report by the UK-based Index on Censorship.

Whether the region suffers from a prevalence of innocuous art is open to debate, and some critics have encouraged programmers and artists to reclaim controversy. However, the stakes are high for government critics in much of Southeast Asia, where those who fall foul of the authorities can run into harsh punishments.

On the other hand, it is part of the artist’s remit to be innovative and react to their surroundings. “No matter what difficult situation they are experiencing they always find ways to comment. They’re kind of like rebels,” says Khim Ong, curator of Art Stage’s annual Southeast Asia Platform, a showcase of about 30 regional artists. “In relation to oppressive environments, artists still thrive. You get heroes when you have problems, right?”

Many Southeast Asian artists have lived or worked in an oppressive society and that is where, according to Yiing, creativity can come to the fore.

“That’s why, in Southeast Asia, which country has the most vibrant art scene? Indonesia, and that’s because of the political situation [in recent decades]. And which country is the worst? Malaysia, because we were so peaceful. We don’t have natural disasters, and our government was not too bad. But now the situation is changing, the politicians are causing problems, they are separating the people because we are different races,” she says.

“Overall, [oppression] has to be a bad thing for art. If you cannot say what you want to say – that has to be bad. But if it makes you think differently, forces you to be clever in how you present things, then that’s a creative process as well.”

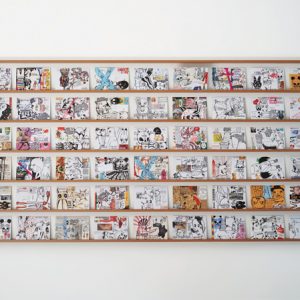

Eddie Hara, a 58-year-old Indonesian artist with a fine line in garish shirts and a sunny disposition to match his humorous comic-book style, takes the idea one step further. He recalls the end of Suharto’s 31-year autocratic rule rather unexpectedly.

“I remember when Suharto finished power in Indonesia, we had new freedom, but many artists were kind of lost,” he says. “It was as if they were saying: ‘Oh, the source of our inspiration just ended.’ Obviously oppression is bad, but it’s also what drives a lot of the best art… Sometimes I could feel it – when you’re under control, under repression, there’s a certain feeling of fighting back. As artists we have to fight with our art.”

The region has not had things easy in the past century, and its artists cannot ignore or neglect that history. As Victor says, it is “an inherent part of us as a region and as individuals” and, perhaps, the region can use its past to inform a unique artistic ecosystem.

“Having passed through the stage of being colonised, having been invaded, having many traumatic experiences, I think [Southeast Asians] are really trying to find their own voice and their own identity,” says Khim Ong. “Being anti-colonialist, then being nationalist and then trying to find a national identity that is non-Western… Trying to find an identity is creating an identity in itself.”

For many nations the need to look forward is just as compelling as the need to look back, perhaps even more so. Artistic rebels may feel strangely lost following the downfall of their natural enemy, but then they have to continue and find new inspiration. “That is when you see the good artists,” says Rudolf, although the Art Stage founder is keen to point out that the region’s diversity means that the same rules cannot be applied across the board.

“Svay Sareth [the Cambodian artist] is a typical example,” adds Rudolf. “He grew up in a refugee camp on the Thai-Cambodia border during the Khmer Rouge years; it’s completely natural that such a history will be part of him as an artist. Compare him to Nyoman Masriadi, an art superstar, who grew up on Bali. It’s a totally different history to Sareth’s. The region is relatively small geographically but it is ten different worlds in its own way.”

Suzann Victor considers the region’s inequalities and the restraints they can place on artists. As ever, she has a more ornate way of thinking about even this most utilitarian of conundrums.

“In Southeast Asia, there is an urgency of expression. I think that the need to be creative, even though you have nothing, is the ultimate subversion of the idea that you’ve got to be able to afford to make art. You think that art has to be oil on canvas? Sorry, you’re wrong.”