“Our part of the world is changing dramatically,” said Singaporean defence minister Ng Eng Hen at a press conference last March. The comments were not a forewarning of political, economic or social upheaval; rather they were a reflection on military expansion in Southeast Asia over the past decade.

The past two years alone have seen several countries in the region augment their military arsenals. In December, the Philippines announced a multibillion-dollar deal to purchase three high-end submarines from an undisclosed source, while Singapore has purchased F-15 fighter jets from the US, and both Malaysia and Indonesia have imported Sukhoi Su-30 jets from Russia.

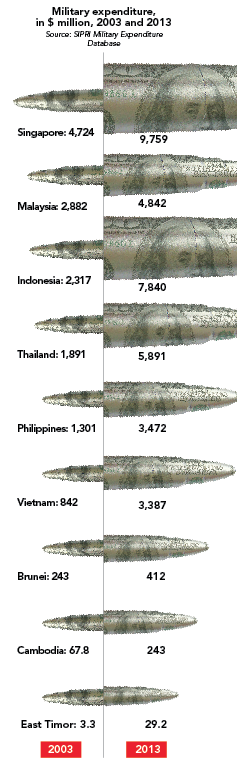

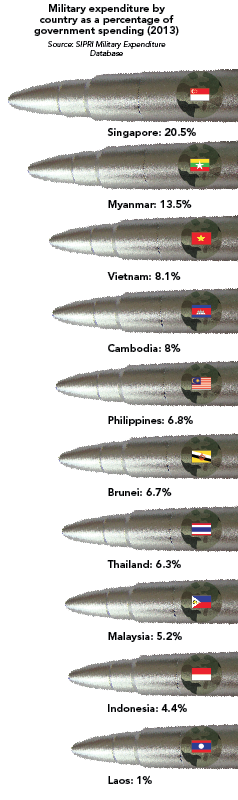

Such high-profile purchases are part of a trend towards expanding defence budgets. Singapore has long been the region’s largest investor in its military, dedicating $9.7 billion to defence in 2013 – almost 20% of the national budget, according to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) statistics – but in recent years even countries such as Cambodia and Brunei are spending more than $200m annually.

Collective defence budgets in the region amounted to $35.9 billion in 2013 – double what they were worth in 1992 – and spending is expected to increase to more than $40 billion by 2016, according to SIPRI. For some nations this growth is said to be a defensive measure against growing Chinese aggression in the region; for others it is a natural product of an expanding economy.

But has increased defence spending resulted in an expanding domestic manufacturing industry? And how do Southeast Asian companies fare on the world stage?

The largest defence manufacturing company in the region is arguably Singapore Technologies Engineering (ST Engineering), which produces a range of military hardware, from simple arms and ammunition to complex components for submarines and aeroplanes. The only Southeast Asian firm to be included on SIPRI’s list of the top 100 arms-producing and military services companies worldwide, it ranked 49th in 2013. In the same year, its defence sales amounted to $2.02 billion, up from $1.89 billion the previous year, according to company records.

Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand also boast sizeable defence companies. In Malaysia, Boustead Heavy Industries is working with DCNS, a French naval contractor, on a $2.8-billion contract to develop six coastal ships for the Malaysian navy, with more than half of the manufacturing to take place domestically.

“There is currently the capability for major defence assets to be assembled and built in Southeast Asia but a large proportion of the key systems and equipment will be sourced abroad,” said Tan Sri Dato Seri Ahmad Ramli Mohd Nor, managing director of Boustead Heavy Industries. “The trend, however, is for certain components of even the most sophisticated equipment to be manufactured locally.”

He added that the Malaysian government is conscious of increasing local participation in the defence industry and has moved to reduce dependence on foreign suppliers. There is also a dedicated defence industry division within the ministry of defence to promote development of the sector.

“As major defence equipment manufacturers overseas become more comfortable with the skills available in the region and the economic advantages of Asean manufacture, we will see more collaborations and joint ventures being formed, leading to the growth of the defence manufacturing sector,” Ahmad Ramli Mohd Nor added.

While there is optimism that the defence industry is advancing smoothly, not everyone is convinced that progress will be rapid. According to Jon Grevatt, an Asia-Pacific military industry analyst at research company IHS Jane’s, the defence industry in Southeast Asia is limited at present.

On average only 20% of defence budgets in the region are spent on procurement, he said, of which only 30% is spent on locally manufactured hardware and services – and these percentages have not changed in recent years. “Across the whole of the region for 2014, I estimate that only two to three billion dollars was spent on locally manufactured goods, which is not a lot,” said Grevatt.

Most regional companies, he added, are capable of offering basic manufacturing and services: land systems (firearms, ammunitions and simple vehicles); navy vessels; and maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO). While progress has been made in these areas in recent years, Grevatt said that Southeast Asian defence companies continue to fall behind in ‘indigenous manufacturing’ – the creation of original systems and hardware by the companies themselves.

“Most arms production in Southeast Asia is the licensed production of foreign-developed weapons,” said Grevatt. Known as ‘industry collaboration’, an example of this is the deal between Boustead Heavy Industries and DCNS. While much of the manufacturing takes place in Malaysia, the designs and technologies are owned by DCNS. “So a country might say they’re manufacturing such and such machines or hardware, but what they’re actually doing is manufacturing under licences,” Grevatt continued.

This type of agreement has both positive and negative impacts on the industry. The fact that Southeast Asian companies do not have their own indigenous technologies – or, at least, do not have advanced indigenous technologies – diminishes their presence on the world stage. However, industry collaborations do allow the companies to develop and grow, learning new techniques and picking up knowhow.

“The ultimate objective is for companies in the region to be able to build their own hardware and technologies, especially advanced ones such as submarines and aircraft,” Grevatt said.

However, the ability to achieve such goals could be stymied by a number of factors. The global economic crisis has had a direct impact on Western defence companies, which has made the armaments industry a “buyer’s market”, explained Richard Bitzinger, a senior fellow and coordinator of the military transformations programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies in Singapore.

“The competition among suppliers is so fierce that customers can usually cut quite good deals,” said Bitzinger. “This reduces much of the strategic need for finding an indigenous source of arms among Southeast Asian nations, meaning most regional countries find it is easier – and cheaper – to import weapons and spares.”

Companies in Russia, the US, China, South Korea, France, the UK and Germany remain the largest exporters of military equipment to Southeast Asia. At a time when these governments’ budgets are being squeezed they will target new markets, such as Southeast Asia, if it is profitable to do so.

“Both Indonesia and Malaysia are on the UK government’s priority list for arms exports, so there is obviously

a strong level of interest,” said Andrew Smith, a spokesman for the Campaign Against Arms Trade. “The fact that the UK has continued licensing arms to Thailand, despite the military coup, is a sign that human rights and democracy are seen to be less important than arms company profits,” he added.

The ability of regional nations and companies to progress from manufacturing licensed products to developing their own technologies is also dependent on high levels of government investment and patience, which Bitzinger said has not always been forthcoming.

“It takes a long time and a lot of money to grow an arms industry, and that requires long-term political commitment on the part of governments to ensuring that this development goes forward with a constant source of funding,” he said.

Indonesia in particular, he added, has long harboured ambitions of becoming a major regional producer of arms, but this has been “stymied by a lack of guaranteed long-term funding support from the government”.

There is also the fact that many of the largest arms manufacturers around the world can rely on multibillion-dollar defence budgets in their operating countries. Lockheed Martin, based in the US, is one of the world’s largest defence contractors. In 2009, contracts with the US government accounted for $38.4 billion, or 85% of the company’s sales, according to its annual report.

While military spending is increasing in Southeast Asia, the sums pale in comparison to many other parts of the world. In 2013, US military spending was $640 billion and China’s was $188 billion. Collectively, Southeast Asian countries spent $35.9 billion in 2013, according to SIPRI – slightly more than South Korea’s $33.9 billion expenditure.

Many experts agree that Southeast Asian companies are unlikely to become key players on the international stage any time soon. However, progress is slowly taking place and, as regional governments continue to allocate increasing amounts of money to defence budgets, local producers and military service providers should continue making a killing.