When Kaida Noor was learning embroidery this time last year, little did she expect she was going to be helping as a volunteer in what is currently one of the largest humanitarian emergency operations in the world. The 24-year-old single mother is a Rohingya refugee living in Chakmarkul camp in Bangladesh. She arrived in the country four years ago during a wave of violence against her ethnic minority in Myanmar’s Rakhine State.

She speaks about her recent volunteer work, which included helping to transport a man named Mohamed whose feet were so swollen he couldn’t walk: “Three times we carried him to an MSF hospital.”

She’s talking about the France-based Médecins Sans Frontières, or Doctors Without Borders, which has a number of health centres and 2,800 staff, mostly Bangladeshis, to care for refugees in the country.

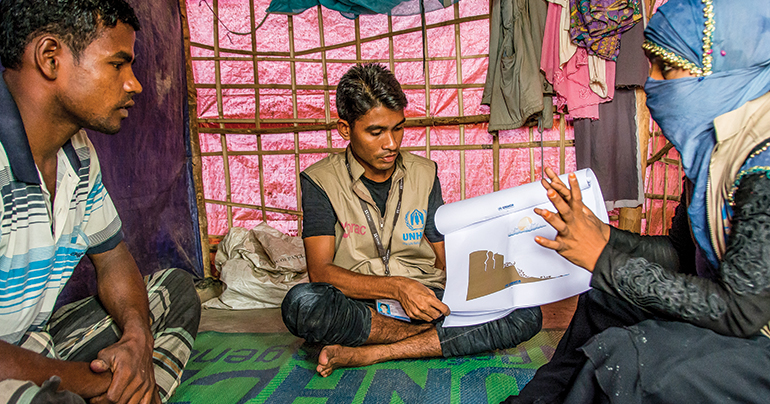

Kaida and her 21-year-old colleague Amin Soyot, also a Rohingya refugee, are, in humanitarian-speak, “community outreach members”, or “COMs”. They’ve been recruited in the refugee camps and mentored by the UN refugee agency UNHCR and its NGO partner Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee (BRAC). They go shelter to shelter disseminating information on hygiene and vaccinations, medical treatment and education facilities, and to accompany the sick, elderly and young to service points – as Kaida did with Mohamed. Now they’re playing a key part in helping their fellow refugees prepare for the much-feared monsoon season.

Chakmarkul camp is just one of more than 30 refugee sites near Cox’s Bazar, a seaside resort in southeast Bangladesh and the country’s most popular holiday destination.

Before August 2017, over 30,000 Rohingya refugees were officially registered in Bangladesh, people who had arrived in the country fleeing waves of violence in neighbouring Myanmar going back decades. After new anti-Rohingya violence erupted in Myanmar that month, over 600,000 refugees arrived in Cox’s Bazar between then and early December – a number that swelled to around 700,000 by the end of May, rivaling the population of a city.

The value of COMs

Chakmarkul is one of the smaller sites near Cox’s Bazar, sheltering around 13,000 refugees. Wander around for ten minutes, and one becomes lost in a sprawling maze of shelters packed against one another, covering every available square metre of hillsides and plains. In this camp, 21 COMs like Amin and Kaida are kept busy.

Back home in Myanmar, Amin was a private tutor of Burmese, English and maths. He remembers the day houses in his village were burned and people tortured and killed. “Here I’m free to walk around the camp. Here I can sleep at night,” he says. He fled across the border in mid-September last year with his parents, a few uncles and six siblings. A cousin stayed behind. They have no news from him.

On their rounds, Amin and Kaida don’t restrict themselves to their official duties as COMs. “Sometimes people lose their documents – for example, their food ration card,” Kaida explains. “We then get the mosque to make an announcement to help [get] it back.”

It’s this position of trust that makes the volunteers so important in bridging the gap between the refugees and aid workers. It’s also crucial while talks continue between the Bangladeshi and Myanmar governments about sending Rohingyas back to Myanmar – talks which create fear and anxiety in the community, along with suspicion of any kind of population census or survey.

“The COMs are part of the community, so they’re trusted and people talk more openly to them,” says a Bangladeshi who works with the refugee community inside the camps and who wishes to remain anonymous. “Although I can speak the same language, if I were to go around with a questionnaire about diphtheria… it would be much harder or impossible to get the data.”

Aid organisations have long enlisted the help of refugees like Amin and Kaida to help their fellow refugees. Deploying them so early in an emergency operation is a pioneering approach, according to Vipawan Pongtranggoon, a protection officer at UNHCR.

“We started the COMs programme last December, barely four months after the massive influx of refugees,” says Pongtranggoon. “Normally this is done much later because, during the early period of a disaster, humanitarians are preoccupied with life-saving activities and construction of basic infrastructure. A refugee volunteer programme is usually set up when the situation has stabilised. Cox’s Bazar is different because the [refugee] community has only just arrived, and we’re already tapping into their resources.” She thinks the programme could become a model for future emergencies.

Bracing for disaster

The Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar district are now the largest refugee community on the planet. The vast scale of the operation and the speed with which the crisis has unfolded has overwhelmed the Bangladeshi government and aid organisations. As a result, there’s a lack of space to house the additional 700,000 refugees who have arrived since August last year, and living conditions at the sites are appalling.

Humanitarians fear the monsoon season will increase the misery exponentially. Between 1877 and last year, Bangladesh was hit by 154 cyclones – and the coastal region of Cox’s Bazar district has always been particularly vulnerable. In 1991, Cyclone Gorky killed 139,000 people in Cox’s Bazar and Chittagong, a major seaport city on the same coastline. Thanks to national preparedness, fewer than 25 people have been killed in a cyclone since 2015. But the recent influx of over 700,000 people living in temporary shelters, combined with high population density, means that a cyclone would turn these camps into nightmarish urban-style disasters. The deforestation that’s being done to accommodate refugees removes natural barriers to the destructive power of extreme weather.

Humanitarian organisations estimate that, as of May 2018, over 200,000 refugees are living on land prone to landslides and flooding, and say they are in urgent need of relocation. This year, the rain had just begun when it claimed its first victim: Adiba Begum, an eight-year-old Rohingya girl, was killed by a landslide on 7 May as she returned home from collecting firewood.

The massive effort by international and local aid organisations has engineers, heavy machinery and thousands of labourers flattening land, digging floodwater canals and fortifying structures. There’s been a rollout of vast vaccination campaigns against diphtheria and cholera. Early-warning response systems have been set up for deadly conditions like acute watery diarrhoea and acute respiratory infections, which, together with mosquito-borne diseases, can see severe outbreaks during monsoons.

Despite this gargantuan operation, aid workers and refugees are bracing for the worst. Brick-and-mortar houses cannot be built because the Bangladeshi government does not allow permanent structures to house temporary refugees. Hilly topography means that many shelters are standing vulnerably on cliff sides and steep hills. Many fear a cyclone could sweep through and flatten the camps. UNHCR is equipping every refugee family with a reinforcement kit containing bamboo poles, ropes, tarps and sandbags. They’re also airlifting in thousands of tents to provide emergency shelter for those most at risk.

Asked about their hope for the future, Kaida is blunt: “Peace”

A lack of space limits relocation efforts. There are no current plans to evacuate the refugees to cyclone shelters – there aren’t enough of them even for the host communities. Refugees have been advised to stay put in the event of a cyclone.

That’s why the work that Rohingya volunteers like Kaida and Amin are doing is so important. They’ve been distributing life-saving practical advice about flooding and landslide risks using a method they call “storybook”. With pictures showing the risks of landslides, they manage to get the right messages across.

“After coming to Bangladesh, they didn’t receive any kind of [instruction] about our country’s geographic condition and the natural hazards every year during the monsoon period,” says Farheen Masfiqua Malek, who manages BRAC’s COM programme in Chakmarkul. Landslides pose one of the biggest hazards to the camps, she says.

A new hope?

Asked about their hope for the future, Kaida is blunt: “Peace”, she says, while Amin hopes that one day the Rohingya will be recognised as Myanmar citizens and enjoy the same freedoms as the rest of the population. Asked to show his most valuable possession, Amin digs up his national identity papers and land registration documents, neatly wrapped in plastic. Kaida’s only possessions are a golden nose stud shaped like a flower – and the clothes on her body.

Like most of their fellow refugees, this young pair has witnessed horrors and lost everything, including their rights to citizenship. Yet, in Chakmarkul camp, they’ve taken on the roles of professionals with pride. They have been trained to use tablet computers in place of paper forms, preserve data accurately and take photos so they can report back with visual evidence of shelters that need urgent fortification against storms. When they’re not going door to door visiting refugees, the COMs are training in areas like code of conduct and protection principles, while some become specialised in sexual gender-based violence, child protection and psychosocial care.

Though they are indeed worried about deadly cyclones, Amin and Kaida have found a new purpose. The pair embody the humanitarian principle that refugee communities are resilient and shouldn’t be treated as mere recipients of aid – assistance is more effective and transparent when these communities participate.

Their positions are empowering, too, says UNHCR’s Tahmina Parvin: “They benefit psychologically, especially the women. You can see it in their eyes how confident they have become.”